Dire Consequences for the National Register

In early March 2019, the Federal Register announced that the Department of the Interior, via the National Park Service, had proposed changes to the rules for nominating properties to the National Register of Historic Places. The impending revisions would have dire consequences, privileging large landowners, allowing federal agencies to block the nominations of some properties, and removing Section 106 protections from others. The public has been asked to comment on the proposed changes prior to an April 30, 2019, deadline. The Cultural Landscape Foundation has submitted a letter voicing strong opposition and encourages others to do so as well.

Several of the new provisions were promulgated under the guise that they would “implement the 2016 amendments to the National Historic Preservation Act,” but they far exceed the intent of that legislation. The revisions were not only a surprise to the preservation community; they set off alarm bells in other federal agencies and among the ranks of State Historic Preservation Officers (SHPOs) and Tribal Historic Preservation Officers (THPOs) across the country, many of whom have already submitted letters of protest. At an April 4 meeting of the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, members “expressed their serious concerns with the proposed language and its intentions; that the process changes seem unnecessarily adversarial; and the NHPA goes beyond property rights issues.”

New Powers to Block Nominations to the Register

Among the most consequential revisions are those that would, in effect, establish federal agencies as the sole conduits for nominating federally owned properties to the National Register by removing and altering language from Title 36 of the Code of Federal Regulations (36 C.F.R.). Under the revised regulations, by simply declining to act, federal agencies could block nominations of federally owned property to the Register. Yet federally owned resources are intrinsically public resources, and silencing the public’s voice in determining their historical or cultural significance does not serve the public interest.

The federal government is the steward to more than 28 percent of all the nation’s land—some 640 million acres—yet federally owned land per se does not enjoy any special protection and is frequently targeted for natural-resource extraction. A recent study indicates that 90 percent of the land under the control of the Bureau of Land Management has now been made available for lease by the oil-and-gas industry alone. Removing public input entirely from the process by which federal lands achieve historic designation can only be construed as a significant reduction in the protection of public lands.

Why would the Department of the Interior be motivated to put forth such changes? To quote a famous Latin phrase that guides rational analysis: Qui Bono—"for whose benefit?” Certainly, any new mechanism to block large tracts of federally owned land from being listed in the National Register would be a major boon to extractive industries, which have already benefitted significantly from a reduction in the size of the nation’s national monuments.

Larger Landowners Would Have More Say

Other potentially devastating revisions pertain to the question of owners’ objections to listing their properties in the National Register, in particular, the cases of historic districts in which multiple property owners have a stake in the district’s listing. The current language in Title 54 of the United States Code clearly states that “if the owner of any privately owned property, or a majority of the owners of privately owned properties within the district in the case of a historic district, object to inclusion or designation, the property shall not be included on the National Register or designated as a National Historic Landmark until the objection is withdrawn [emphasis added].” In other words, one owner, one vote. The proposed revisions to 36 C.F.R. would fundamentally alter the intent of that legislation by mandating that a property shall not be listed in the Register if the “owners of a majority of the land area of the property” [emphasis added] object to the listing. Note that the original statutory language guarantees that each owner within a given district has an equal say regardless of the size of their property, while the proposed revisions would privilege the interests and opinions of those who own larger parcels within a given district, such that a single property owner could defeat a listing over the objections of scores of other owners. Again, the Department of the Interior has offered no rationale for such a substantive change.

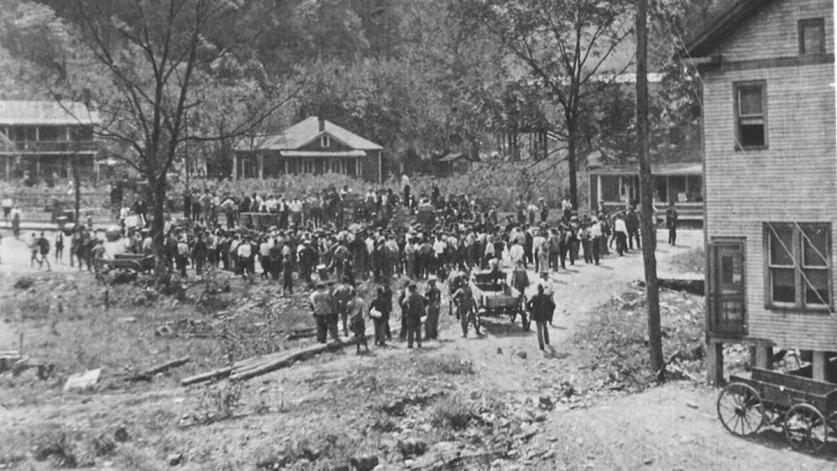

To see the potential effects of such a change, consider the case of the Blair Mountain Battlefield, the site of the largest armed uprising in American history since the Civil War, where the culminating battle in the West Virginia Mine Wars took place. Covering some 1,669 acres and exceptional for its importance to labor history, social history, and politics, the battlefield was listed in the National Register of Historic Places on March 30, 2009, but was delisted within months after questions arose about the number of owners who objected to the listing. In June 2018, the Keeper of Register relisted the site, having found that of the 83 owners of real property within the district, only 28 had registered valid objections, some 33%. Yet had the revisions now being proposed been in effect, the coal companies that own large swaths of the battlefield, and who had permits at the ready to mine the area, could have blocked the listing.

These proposed regulatory changes seem to be specifically intended to benefit corporations. In the case of the Blair Mountain Battlefield, the property became a part of the National Register because the vast majority of landowners approved the nomination. However, under the new regulations, the coal companies would have prevented the preservation of Blair Mountain and facilitated its destruction. This is a blatant attempt to stifle the voices of small landowners and favor the voice of big corporations. It is outrageous and wrong.

-Professor Charles B. Keeney, Ph.D., board chairman, Friends of Blair Mountain

Negating Section 106 by Not Determining Eligibility

Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act requires federal agencies to consider the effects of their undertakings on properties that are listed in, or are eligible for listing in, the National Register of Historic Places. Current regulatory language in 36 C.F.R. 63.4 (c) is as follows:

If necessary to assist in the protection of historic resources, the Keeper, upon consultation with the appropriate State Historic Preservation Officer and concerned Federal agency, if any, may determine properties to be eligible for listing in the National Register under the Criteria established by 36 CFR part 60 and shall publish such determinations in the Federal Register. Such determinations may be made without a specific request from the Federal agency or, in effect, may reverse findings on eligibility made by a Federal agency and State Historic Preservation Officer. Such determinations will be made after an investigation and an onsite inspection of the property in question [emphasis added].

According to the proposed revisions, paragraph (c) would include new language to “clarify that the Keeper may only determine the eligibility of properties for listing in the National Register after consultation with and a request from the appropriate SHPO and concerned Federal agency if any [emphasis added].” But that is hardly a clarification. Rather, the proposed language represents a dramatic change that would allow federal agencies to block the Keeper of the Register from issuing a determination of eligibility regarding federal properties. In other words, federally owned, National Register-eligible properties would no longer be guaranteed the protection of Section 106 reviews. Moreover, the Keeper would no longer serve as a check on federal agencies in situations in which it is the actions of the agencies themselves that may imperil historic resources.

Hundreds of comments from the public have already registered intense opposition to these changes, but thousands of comments are needed. Please add your voice of opposition to these ill-conceived, undemocratic regulatory changes, which represent a breathtaking shift in the processes of nominating properties to the National Register of Historic Places, “the official list of the Nation's historic places worthy of preservation.”