Brooklyn Heights Promenade Faces Uncertain Future

Stretching between the Brooklyn Bridge and the Atlantic Avenue Interchange, the Brooklyn Heights Promenade is a 1,826-foot-long platform and pedestrian walkway integrated with and cantilevered over the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway. A daring engineering feat, the promenade is a by-product of competing proposals for the highway’s route that were resolved during World War II. The promenade’s unique location, affording views of the Brooklyn Bridge, Lower Manhattan, and New York harbor, has transformed it into a major public attraction. But as the expressway’s structure nears the end of its design life, the fate of the innovative, cantilevered public park designed atop it by Clarke & Rapuano remains unclear.

History

Although the idea to create a private garden oriented towards Manhattan, rivaling Battery Park, can be traced to a 1820s proposal by Hezekiah Pierrepont, the Brooklyn Heights Promenade (BHP, also called the Esplanade) was an outcome of a bid to construct a highway to connect the boroughs of Brooklyn and Queens in the 1930s. In 1941 Robert Moses, then the Commissioner of the New York City Department of Parks and the Chairman of the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority proposed constructing a portion of the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway (BQE), also known as Interstate 278, through the residential heart of historic Brooklyn Heights. The proposed route would have bisected the neighborhood, even requiring partial demolition of a recently built marble courthouse. Ensuing opposition by neighborhood residents, led by the Brooklyn Heights Association (BHA), defeated the plans for this route, and the BQE’s location was moved to the escarpment along the neighborhood’s western edge.

By hybridizing a park and a stacked highway, [the project] transcends the limitations of single-use infrastructure and, in turn, eliminates the “either/or” dichotomy associated with urban fabric versus infrastructural space.

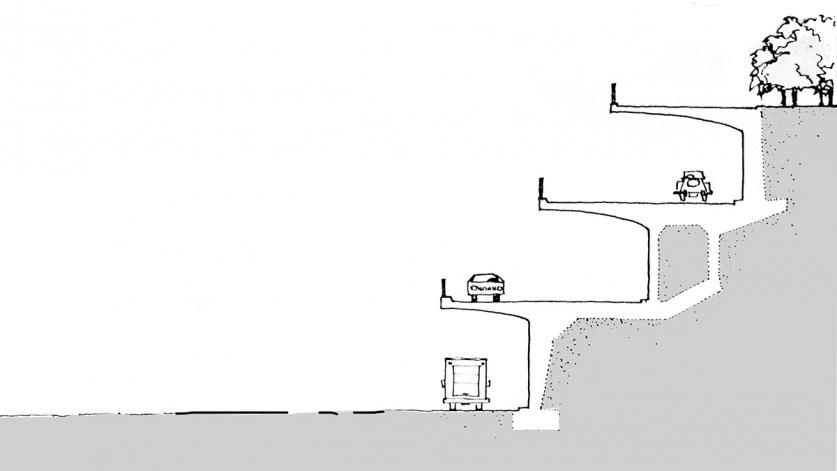

Designed in 1946 by Clark & Rapuano (which was also extensively involved in the design of the surrounding Brooklyn Heights National Historic District), the iconic expressway and public parkway atop it were constructed along the escarpment to conserve space and minimize intrusion in the surrounding neighborhood. Opened in 1950, the eight-block-long, three-level cantilevered structure includes two three-lane roadways on its two lower levels, while the promenade—a public park—occupied the topmost tier at the street level of Brooklyn Heights. The promenade functions as a physical cover atop the two-level highway, mitigating the effects of traffic noise and vehicular emissions on the adjacent neighborhood. The walkway is edged with fencing and lined with wrought-iron benches on the west, affording unsurpassed views of the Brooklyn Bridge, Lower Manhattan, and New York harbor (and sites including the Statue of Liberty, Governors Island, and Ellis Island). The promenade is abutted on the east by a strip of plantings that separates it from the adjoining residential properties and connects to the half-acre Pierrepont playground, Adam Yauch Park in the south, and Fort Stirling Park, Harry Chapin Park, and Fruit Street Sitting Area in the north. An innovatively designed footbridge called the Squibb Park Bridge (just past the northern end of the promenade) links to the shoreside Pier 1 in the recently created Brooklyn Bridge Park, which transformed defunct shipping piers on the Brooklyn waterfront just west of the triple cantilever. In addition to serving the residents who regularly use the walkway and its adjacent playground, the promenade is a magnet for hundreds of thousands of tourists annually, its popularity increasing as tourists flock to New York City in ever greater numbers.

In 1953 a new concern arose when the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, which owned the warehouses still lining the harbor on the west side of Furman Street, sought to replace them with structures up to 70 feet tall. The unprecedented outpouring of protest at the loss of views from the recently built promenade led the city to hastily backtrack, ultimately limiting the height of structures across from the promenade to 50 feet. In 1974 the area was designated a “Special Scenic District,” thus protecting the uninterrupted views from the promenade—a designation that remains in effect today. The promenade is also listed as a contributing feature to the Brooklyn Heights Historic District.

Threat

At almost 75 years of age, the 1.5-mile stretch of the BQE triple cantilever, which supports the promenade, is nearing the end of its design life and requires reconstruction. Although the BQE is state-owned, in 2010, the New York State Department of Transportation (NYSDOT) abandoned its planning efforts to rebuild the structure, thereby requiring the City of New York to undertake that task. The NYCDOT has concluded that by 2026 the triple cantilever will no longer be able to support the weight of heavy trucks, which could force some 16,000 trucks per day onto already saturated local thoroughfares. In September 2018, the NYCDOT took the unprecedented step of presenting two alternative construction approaches for the BQE’s rebuilding. The first, more traditional scenario would involve a lane-by-lane reconstruction that would require neither a temporary roadway nor an extensive closure of the promenade. The NYCDOT has determined that this option could take more than eight years to complete, costing from $3.4 to $4 billion. This would allow the city to improve the safety of the highway, whose outdated design, narrow lanes, and lack of shoulders have contributed to a high crash rate, although there would be an increase in delays and traffic backups from lane closings at night and on weekends.

The second option necessitates the complete closure of the affected portion of the expressway and construction of a temporary six-lane roadway on the level of the Brooklyn Heights Promenade. The revamp would be completed at a cost of $3.2 to $3.6 billion, and the plan has promised several community benefits, including improved pedestrian access from Brooklyn Heights to Brooklyn Bridge Park and more green space around the roadway. Unfortunately, in this scheme, the promenade-level highway would be expected to absorb traffic from the roadways below, rerouting some 153,000 cars and trucks to the promenade on a daily basis. That option would also render some of the adjacent residential buildings partially or wholly uninhabitable and threaten the nearby neighborhood with noise, air pollution, and other adverse environmental effects. The NYCDOT has also estimated the project would require the use of the temporary “Promenade Highway” for six years, but the complexity of the triple cantilever’s design and the history of large-scale public-works projects in New York City suggests that the promenade would be unusable for much longer. What is more, there is the very real possibility that once the elevated highway is in place, built at a substantial cost, it may well become permanent rather than temporary, with the promenade disappearing forever.

What You Can Do to Help

In the wake of intense opposition to the proposed plans, Mayor Bill de Blasio stated that his administration is open to considering other ideas, including rerouting the temporary expressway through the Brooklyn Bridge Park, slightly to the west. The BHA met with six prominent civic organizations in November 2018 in the hopes of influencing city and state officials and broadening the base of opposition to the proposed elevated highway that would displace the promenade. The NYCDOT anticipates making a final decision on the general approach to rebuilding the expressway in mid-to-late 2019, following the completion of an environmental review process. The BHA has mobilized the community’s resources to defeat the plan for an elevated highway and to promote a solution that would reduce the impact of the BQE project on the region, the adjacent communities, and the promenade itself.

Working with a local architect and consulting engineers, the BHA has also developed an alternative engineering concept that it presented to the NYCDOT for its evaluation. The BHA’s traffic consultant is working on recommendations for reducing traffic volume on the BQE to facilitate alternate rebuilding approaches. The BHA has reached out to its neighborhood’s elected officials and is committed to working with them to enact legislation to support potential traffic-management measures and a better engineering solution. The development of a broad coalition of civic and advocacy groups is a critical part of the BHA’s strategy to ensure that a better rebuilding plan is implemented, one that will ensure that the promenade remains an asset for current and future generations.

Stay informed about the threat and get the latest updates by visiting the news page of the BHA website.

Peter Bray has been engaged in affordable housing, transportation, land use advocacy and historic preservation efforts in New York City since 1982 and has been the BHA’s Executive Director since 2015.