Finding Florida’s ‘Flagship 50’

It is perhaps counter-intuitive that structures built within the scope of current cultural memory are those most apt to disappear from the historical record, along with an understanding of their contribution to the history of the built environment. In Florida, for example, there is currently no comprehensive record of the state’s historic Modernist landscapes and structures, which have already begun to disappear. In an effort to identify these resources before it is too late, the Historic Preservation Program at the University of Florida is undertaking a groundbreaking, multi-tiered survey of Florida’s significant Modernist buildings, sites, and landscapes. The project, Florida’s Mid-Century Modern Resources: 1945-1975 (otherwise known as My Florida Modern), includes three historic context statements and the identification of “50 Flagship Structures.” The overall project aims to document the range and variety of designed resources that give Florida its unique character and to provide a framework to guide future preservation, land use, and planning efforts. The results of this statewide survey—compiled with the input of collaborative partners—will be freely available to the public, as well as municipal and regional planning agencies who can then begin to take stock of Florida’s Modernist assets. The survey can also serve as the foundation for the future study of individual buildings, building types, design movements, architects, or geographic areas.

FLORIDA’S POSTWAR LANDSCAPES:

Florida’s historic cultural landscapes include not only urban plazas and parks, but also large-scale suburban developments near the coasts, massive resort facilities, and college campuses that sprung onto a seemingly blank canvas. After World War II, developers flocked to the state, seeing it as a tabula rasa for new projects. The swamps, pine forests, fresh-water springs, and thousands of miles of coastline (paired with an unfortunate absence of environmental awareness or protections) provided prime territory for expansion. The mid-century extension of interstate highways to the southernmost points of the state reinvigorated the tourism industry and brought new swaths of land for homes and resorts within reach.

One well-known landscape that developed in the postwar period is the Lincoln Road Mall, in Miami Beach, designed by Morris Lapidus in 1960 and listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Lapidus—a rebellious Modernist known for his joyful designs and anti-minimalist credo of “Too Much is Never Enough”—created an exuberant six-block-long pedestrian mall from an early-twentieth-century commercial street. Modernist A-frame sculptures, cooling pools of water, and lush vegetation changed a picture of urban decay into a sophisticated shopping district. In time, Lapidus’ design began to deteriorate and lose favor, like other pedestrian malls across the country. But in 1997, the site was renewed by landscape architect Martha Schwartz and was ultimately redesigned again, in 2010, by Raymond Jungles, whose plan uses biofiltration and native plants to create an urban oasis of carefully choreographed spaces.

A lesser-known landscape is the Shark Valley Observation Tower and trail within Everglades National Park. The Brutalist tower was completed in 1965 as part of Mission 66, a billion-dollar program to improve visitor facilities at parks throughout the country in preparation for the 50th anniversary of the National Park Service. At Shark Valley, architect Hubert Bebb, of Tennessee—who also created the Clingman’s Dome overlook tower in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park—designed an inspired, all-concrete Modernist take on the vernacular forms of fire towers and oil-rigs (the site was once used for oil drilling). A fifteen-mile-long paved trail loops from the parking area through the “river of grass” to the tower and back, accessible only to trams, bicycles, and foot traffic. This is a serious trail—there are no shortcuts, and the resident alligators are frequently spotted on the road. The tower stands at the halfway point and provides a 360-degree view of the Everglades from 45 feet in the air. Visitors make the long, slow trek up an elegantly spiraling promenade, elevated above the sensitive landscape.

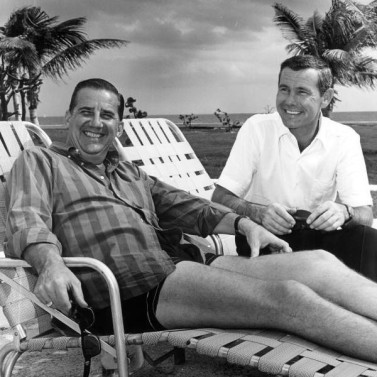

“The company hired television personality Ed McMahon to pitch the project, which was featured in videos, magazine advertisements, and newspapers throughout the country.”

Another rediscovered landscape that represents an early dividend of the survey is Rotonda West, a massive suburban development in Charlotte County, near the Gulf Coast. The development was the brainchild of Jim Stein, who dreamed up a circular community divided into pie-shaped wedges on a former cattle ranch owned by descendants of Cornelius Vanderbilt. An anecdote recalls that Stein was inspired to break away from the grid plan by the water mark of a cocktail glass on a bar napkin. The 35,000-acre property was mostly undevelopable swamp, but Stein moved forward on improving some 2,600 acres of it by dredging 32 miles of navigable canals, six feet deep and 60 feet wide, to provide water access to the planned home sites, along with seven golf courses (one for each day of the week) and commercial and recreational facilities. The company hired television personality Ed McMahon to pitch the project, which was featured in videos, magazine advertisements, and newspapers throughout the country. McMahon received a home overlooking the golf course, custom-designed by Miami architect Carson Bennett Wright. Rotonda West was also the location for the first annual (and subsequent) "Superstars" competition, broadcast by ABC television, a two-hour sports extravaganza featuring boxer Joe Frazier and football player O.J. Simpson. Edward Durell Stone was in talks to design a Modernist clubhouse in “The Hub” at the center of the round plan. Rotonda West began selling lots in 1969 but was in bankruptcy by 1975. In the end, only 600 homes were completed, as a growing environmental movement (marked by the passage of the Environmental Protection Act) heralded the end of water-side residential canal projects. A lawsuit against the company and McMahon was organized by more than 1,000 plaintiffs, declaring that the company and pitchman had purposefully perpetrated a land-fraud scheme and artificially increased lots prices to deceive purchasers, most of whom had never visited Florida.

IDENTIFYING 50 FLAGSHIP STRUCTURES:

A key component of the project is selecting “50 Flagship Structures” that represent Florida’s design environment at mid-century. The initial survey of 350 structures and landscapes will be whittled down to 50 that represent the scale, scope, materials, and intent of Modernist design, as well as the prevailing cultural and economic concerns of the period. The 50 flagship structures will represent both high-style and vernacular designs and will include both well-documented and newly rediscovered resources, rather than a strict presentation of typologies or a “best of” list. For example, the vernacular form of the ranch house and suburban developments will be acknowledged, as will the work of John Johansen at the Orlando Public Library (1966), a Brutalist, all-concrete work by a master architect. Public participation is critical to discovering new places and understanding cultural priorities for recognition and preservation. The public is invited to nominate Modernist landscapes or buildings for inclusion in the “50 Flagship Structures,” either by visiting the My Florida Modern Facebook page or by tagging a photograph on Instagram, Twitter, or Snapchat, with #myfloridamodern.

The project is funded by the University of Florida and sponsored, in part, by the Florida Department of State’s Division of Historical Resources. The effort is being led by the present author and by Morris Hylton, III, director of the University of Florida’s Historic Preservation Program, assisted by a team of graduate students. The research phase includes an analysis of publications from the period, such as monthly issues of Florida Architect from 1954 through 1975, to discover the architects, manufacturers, materials, and structures that were heralded as groundbreaking then, but that lack recognition today. Additionally, the team will conduct research at the George A. Smathers Libraries at the University of Florida, which maintains the largest architectural collection in the state.

The success of the project depends upon strong input and cooperation of collaborative partners from across the state. These partners include professional organizations, private companies, non-profit groups, governmental agencies, and educational institutions, such as the Dade County Heritage Trust, the Florida Trust for Historic Preservation, and Gainesville Modern. With their help and the public’s involvement, Florida’s Modernist legacy can still be recognized and relevant.