Japanese-American Landscape Architects Leave Lasting Impacts

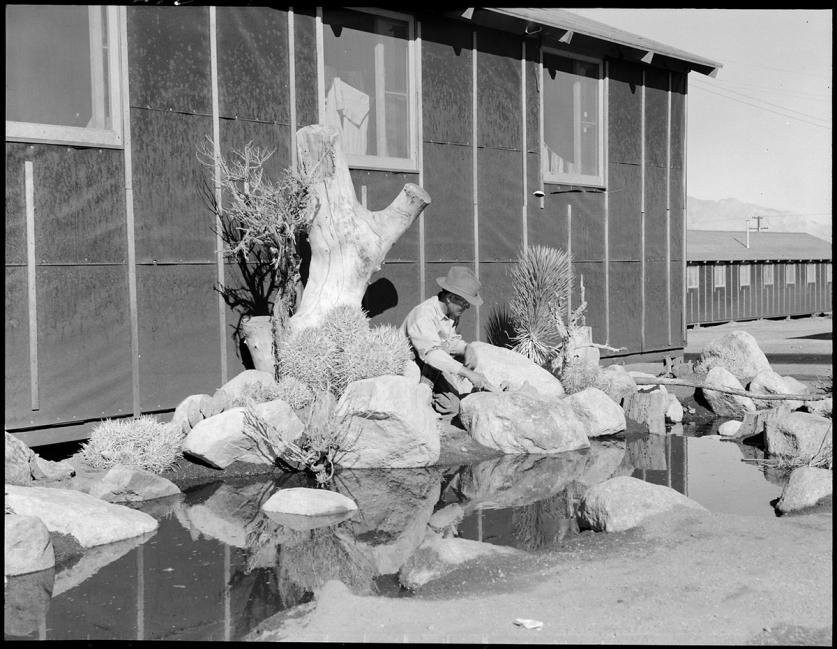

Editor’s note: All of the photographs in this feature were taken by Dorothea Lange, who was hired by the the War Relocation Authority in 1942 to document the relocation of Japanese-Americans. Upon review of her images, military authorities impounded her photographs for the duration of the war.

It's been almost 75 years since an executive order by Franklin Delano Roosevelt resulted in the internment of more than 100,000 persons of Japanese descent during World War II, a majority of whom were American citizens. Internment affected every profession, from the fine arts to military personnel, and landscape architecture was no exception. San Diego-based Joseph Yamada recounted the year and a half he spent in Poston Internment Center in Arizona for TCLF’s Pioneers Oral History series in 2013. He took the opportunity to discuss an early encounter with landscape in the camp:

…they all had beautiful waterfalls, beautiful bonsai. I mean, when you walked from block to block, that in itself was exciting to see. What are they doing on block 323? Look at the shelter they did on 326. They built wonderful shelters.

Yamada goes on to describe how the community constructed their own circulation system:

We designed our own walks between the units because it was so muddy, there was no concrete, no walkways. All the spare pieces of wood from building the barracks, was put in this huge pile. And the guys would go there and they’d build or find these slats. They had to be about three feet wide so that you could build your section from my door to his door…

In preparation for the publication of TCLF’s forthcoming volume on pioneering landscape architects in the post-war era, it became apparent that eight practitioners were associated with Japanese-American internment. Each of their experiences was manifested in some way in their careers. What follows are excerpts from the biographical essays of four practitioners: Shinji Nakagawa, who was born in Japan but interned in Manzanar Relocation Center in California after his family immigrated to the U.S.; Mai Arbegast, who was interned at Heart Mountain Relocation Center in Wyoming; Satoru Nishita, whose family was sent to Poston Internment Center in Arizona, where he graduated from Poston High School; and Isamu Noguchi, who volunteered to work (and live) on an internment camp in Arizona.

Other landscape architects in our database who are associated with internment include: Asa Hanamoto, Masao Kinoshita, Kenichi Nakano, Hideo Sasaki, Robert Murase, and Frank Okamura. Most of persons mentioned here were based on the west coast, but their designs held wide-reaching influence, from Babi Yar Park (a WWII memorial) in Denver, to the gates of the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum constructed for the 1984 Summer Olympics.