The Landscape Legacy of Cleveland

Great Lakes Formation/Early Indigenous History

Approximately 14,000 years ago, the world’s largest concentration of freshwater by total area began to form. Retreating glacial sheets left behind basins that filled with meltwater, today known as the Great Lakes. Prior to European contact, the surrounding landscape would have been dotted with mounded earthworks created by the Native Peoples of the Whittlesey culture, who inhabited the land near the banks of present-day Lake Erie and its connecting rivers.

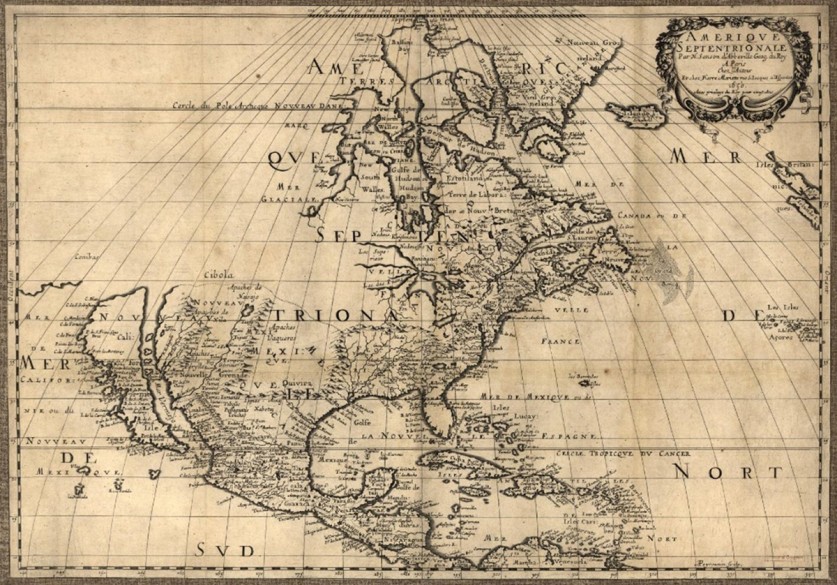

European Contact

Up until the first decades of the eighteenth century, the Lenape, Oneida, Ottawa, and Wyandot peoples sought refuge south of Lake Erie in the Cuyahoga Valley, where they hunted and fished in the riparian ecosystems and participated in the fur trade with Europeans. In 1794, the U.S. victory at the Battle of Fallen Timbers and the subsequent Treaty of Greenville opened most of modern-day Ohio to white settlement, displacing Native peoples to Michigan and the west.

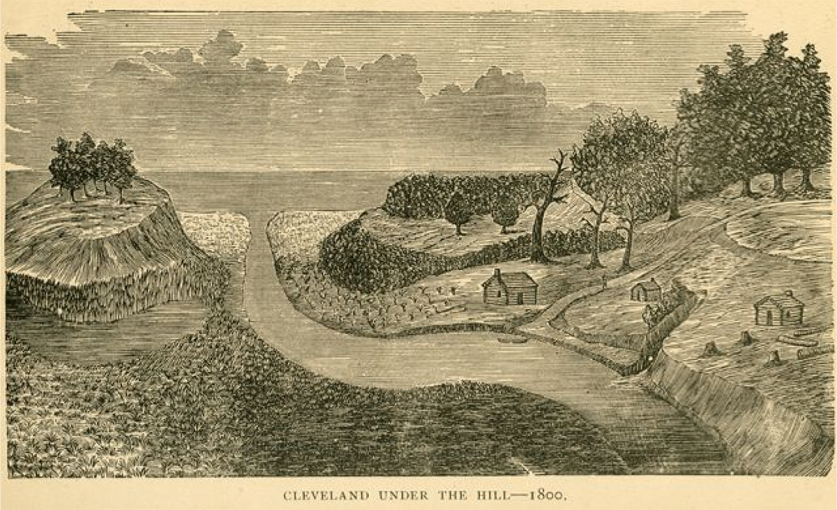

Settlement and Early Development

In 1795, the Connecticut Land Company, a speculation firm, bought three million acres in the Western Reserve, a portion of land in what is now northeastern Ohio granted to the Colony of Connecticut by King Charles II. One of the firm’s largest shareholders, Moses Cleaveland, established a settlement on the bank of the Cuyahoga River in 1796 and called it Cleaveland (over time, Cleaveland would lose the “a”). Featuring a typical New England town plan, Cleveland was centered around a ten-acre public square with parcel-lined roadways emanating from all four sides. Settlement within Cleveland itself was initially haphazard due to its swampy conditions, with many settlers quickly moving to higher ground. While the population of the Western Reserve was growing (1,500 people by 1800), Cleveland’s remained small (reportedly a population of one in 1800). Despite its small population, Cleveland was named the seat of the newly organized Cuyahoga County in 1810, and the following two decades saw steady growth. Newcomers worked as farmers and craftsmen, handcrafting farming tools, barrels, and furniture to be sold regionally. By 1826, the growing population required the establishment of the city’s first public cemetery on Erie Street, replacing an earlier community burial ground south of Public Square.

Transportation Fuels Growth

The opening of the Erie Canal in 1825 and the Ohio & Erie Canal in 1832 repositioned the once-isolated city into a favorable trade hub with lucrative connections to the economically vital East Coast. Canal trade attracted development and immigrants from Germany and Ireland, and from 1840 to 1850, Cleveland’s population grew from 6,071 to 17,034. People, news, goods, and trends that once took months to arrive in Ohio now arrived within a fortnight, and East Coast cultural and stylistic influences began to take hold. By the 1840s, Georgian and Greek Revival architecture had replaced the Cleveland vernacular.

Industrialist Era

By 1850, the arrival of cross-country railroad routes in Ohio caused canal traffic to sharply decline but further energized the region’s economy. John D. Rockefeller, who began his career as an assistant bookkeeper with the Cleveland produce firm Hewitt & Tuttle, eventually entered the oil business, and developed a refinery in 1863. The Civil War fueled economic growth, and Cleveland’s oil, iron, and steel industries rapidly expanded with the demand for new materials and new railroads to transport them. Rockefeller’s company, Standard Oil of Ohio, grew to dominate the refining industry, controlling 90% of the market by the 1880s. In the late nineteenth century, Rockefeller and other newly-minted millionaires built mansions along Euclid Avenue, known as Cleveland’s “Millionaire’s Row.”

The city’s economic growth attracted immigrants from across Europe, and by 1890 three-quarters of Cleveland’s population were foreign-born or born of foreign parents. The immigrant population fueled the city’s steel mills, refineries, factories, canal boats, and lumberyards and congregated in crowded rooming houses or tight-knit ethnic communities clustered in the low-lying land of the Cuyahoga Valley.

Parklands and Patronage

While Cleveland’s nineteenth century development rivaled that of other great American cities, it lagged behind in providing adequate parks and open spaces. In the 1860s, Chicago was expanding its already-beloved system of parks and boulevards, while Cleveland’s ten-acre Public Square, the city’s only reserved parkland, was rapidly becoming absorbed by development.

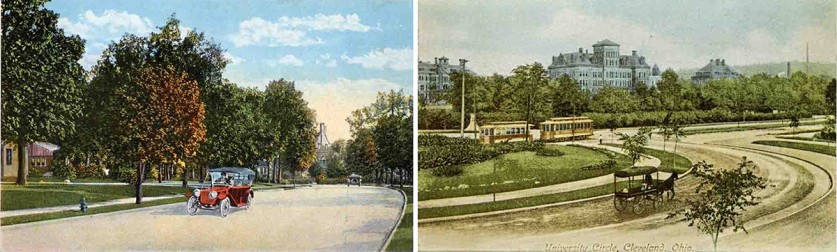

Fortunately, in 1892, the tide began to turn, when William Gordon bequeathed 122 acres of his lakefront estate to the city, enabling the creation of Gordon Park the following year. After the Ohio Park Act of 1893 gave state park boards increased authority to appropriate parkland and issue bonds, a new board of park commissioners was established in Cleveland to acquire parkland through purchase and donation. Landscape gardener Ernest Bowditch was hired by the commission to connect the disjointed parcels via wide boulevards in his General Scheme for Parks and Parkways in 1894 (Edgewater Park, Garfield Park, Wade Oval, Shaker Lakes). By 1896, hundreds of acres of parkland had been donated by generous patrons, such as Jeptha Wade (Wade Park, now Wade Oval), the Van Sweringen brothers (Shaker Lakes), and John D. Rockefeller (Rockefeller Park). Access to parkland increased with the introduction of streetcars in 1890. The network of fast, affordable, and reliable transportation rapidly grew, and by 1903 more than 230 miles of track had been laid, enhancing connectivity for all. With access to downtown improved, wealthy industrialists established their estates further afield. In the early 1900s, landscape architect Warren Manning of Massachusetts was commissioned by industrialist William Mather to design a lakefront estate, Gwinn, and by Goodyear Tire founder Frank Seiberling and his wife, Gertrude Penfield, to design their Arts and Crafts-style estate, Stan Hywet Hall, in nearby Akron.

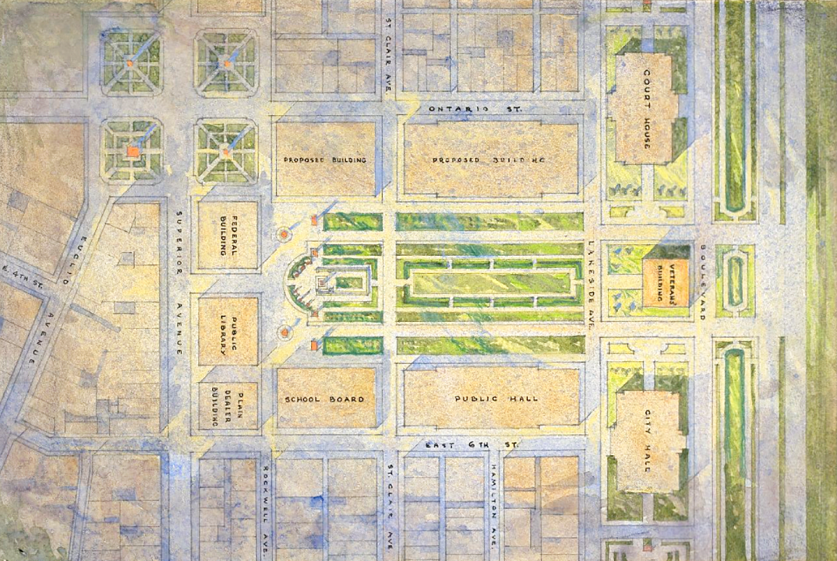

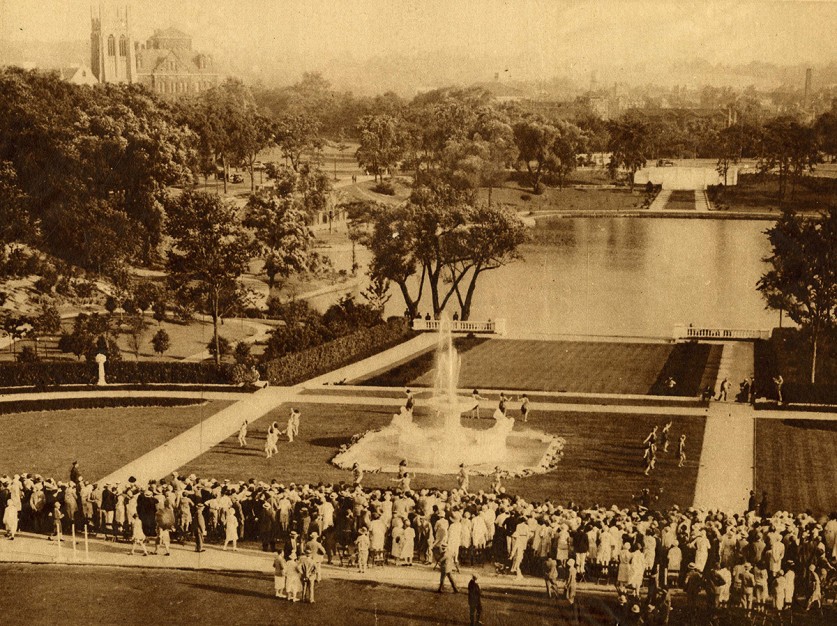

City Beautiful

At the turn of the twentieth century, the city of Cleveland endeavored to assert its status as a center of American prosperity with a grand city plan. Cleveland’s leaders were inspired by the Beaux-Arts plan developed by Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., and Daniel Burnham for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, and in 1903, Cleveland Mayor Tom L. Johnson hired Burnham, with John Carrère and Arnold Brunner, to create a plan for the city’s civic core. Following City Beautiful principles, their 1903 Group Plan recommended clearing 44 acres near the lakefront to construct a wide pedestrian mall surrounded by Beaux-Arts civic buildings of grand scale. Following Burnham’s death in 1912, Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., joined the commission, which continued to oversee the implementation of the plan through the 1930s.

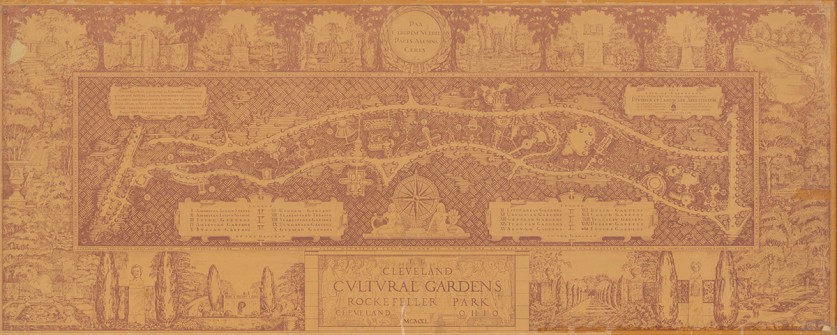

Continuing the city’s legacy of patronage, wealthy Clevelanders began to fund the creation of major cultural institutions. In Rockefeller Park, Leo Weidenthal, publisher of the Jewish Independent, conceived of a series of gardens commemorating the city’s diverse cultural traditions and established the Cleveland Cultural Gardens Federation in 1920.

Over time, many of the city’s educational and cultural institutions, including Western Reserve University and Case Institute of Technology (now Case Western Reserve University), the Western Reserve Historical Society, the Cleveland Clinic, and the Cleveland Botanical Garden, were built in or relocated to the area surrounding Wade Park, which became known as University Circle. In 1916, the Cleveland Museum of Art was established on a tract of land adjacent to Wade Park donated by Jeptha Wade II, with Olmsted Brothers engaged to transform the surrounding 73-acre parcel into the Beaux-Arts Fine Arts Garden.

City improvement efforts permeated Cleveland at all levels. Under nature educator Louise Klein Miller, Cleveland Public Schools implemented a nationally-renowned school garden program to further enhance the city, provide nature education to children, and, later, to support war efforts.

Expansion

As Cleveland’s economy prospered, the growing middle class sought improved living standards beyond the crowded city center and the harsh climate along the riverbanks. As the market for housing bloomed, landowners and developers engaged experienced designers to lay out attractive, deed-restricted suburbs adjoined to parkland or along the desirable higher ground just above the city (Shaker Square, Euclid Heights, Shaker Heights).

In response to Cleveland’s suburbanization and in anticipation of its growth past its city limits, city engineer William Stinchcomb insisted on the need to secure open space in the greater Cleveland environs. In 1917, after years of lobbying, Stinchcomb established the Cleveland Metropolitan Park District (now Cleveland Metroparks), tasked with developing an outer chain of parks with connecting boulevards encircling the city. By 1930, via donations and acquisitions, the Cleveland Metropolitan Park District had acquired 9,000 acres in nine reservations, including Rocky River, Huntington, Big Creek, Hinckley, Brecksville, Bedford, South Chagrin, North Chagrin and Euclid Creek.

Great Depression/WPA

Although Cleveland’s economy slowed during the Great Depression, the city made great strides in capital improvements. New Deal programs provided federal funding for the construction and rehabilitation of bridges and highways; recreational facilities and public parks (Cain Park); and public housing. In 1934, the Landscape Division, a subcommittee of Cleveland’s City Plan Commission overseen by landscape architects William Strong, Arthur Alexander, and Seward Mott, produced plans for the improvement of Cleveland’s city-owned public spaces in a project funded by the Civil Works Administration. A growing cohort of women landscape architects, including Elsetta Gilchrist, Lucille Kissack, and Hannah Champlin, also participated in the Landscape Division, suggesting improvements for the city’s cemeteries, parks, airport, and streetscapes.

With support provided by the Works Progress Administration (WPA), the Cleveland Cultural Gardens expanded within Rockefeller Park to reflect the city’s diverse immigrant communities and became visually unified under the direction of the city’s first Division of Landscape Architecture (see Hebrew Garden, Italian Garden, Irish Garden, Greek Garden). The Great Lakes Exposition, conceived to commemorate Cleveland’s centennial, attracted seven million visitors to the city’s downtown in 1936 and 1937; the demolition of buildings on the Mall to clear land for the exposition fairgrounds aided in the final realization of the 1903 Group Plan.

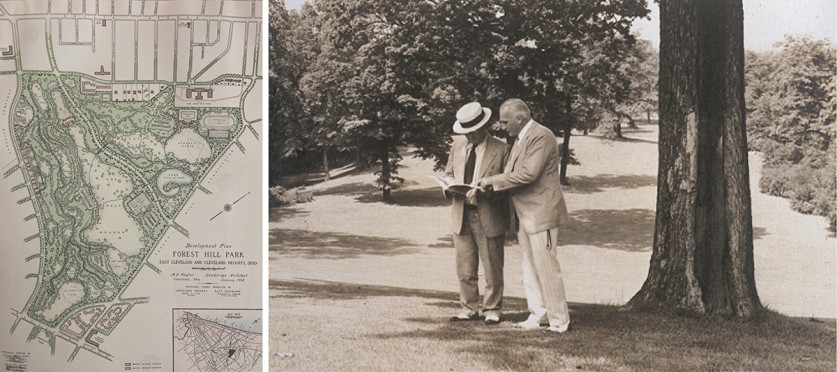

Through the Depression, wealthy Clevelanders continued to support the development of public space. In 1931, mining magnate Albert Holden and his sister established the Holden Arboretum, designed over several decades by landscape architect Gordon Cooper. In 1938, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., hired landscape architect A. D. Taylor to convert his historic estate into the 235-acre Forest Hill Park.

Great Migrations

The first Black settler arrived in Cleveland in 1809, and through the late-nineteenth century Cleveland’s African American population was better integrated than in many other Midwestern cities. Ohio, located on Lake Erie just across the shores of Canada, had been a hotbed for abolitionism and a stopping point on the Underground Railroad. Public burial grounds, including Erie Street Cemetery and Woodland Cemetery (1852) historically included the gravesites of prominent African American and white Clevelanders alike. And while most of Cleveland’s African American population resided on the East Side, the population was evenly dispersed throughout, with no neighborhood having an African American population greater than 5%. The expansion of industry during the First and Second World Wars encouraged the “Great Migration” of African Americans to the north seeking employment and fleeing racial persecution, and from 1910 to 1930, Cleveland saw a 400% increase in its African American population.

Urban Renewal

In response to the city’s changing demographics, increasing numbers of white Clevelanders moved to the suburbs, where non-white citizens were discouraged or prevented from purchasing property. The decentralization of Cleveland diverted development from the city, giving way to a period of decline. With the onset of highway construction, the railroad industry that had once fueled Cleveland’s economy waned.

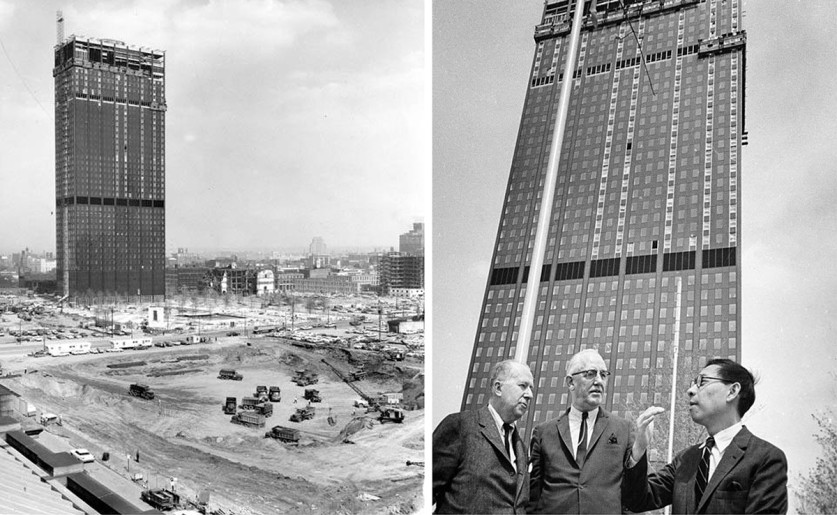

In response, a series of projects aimed at revitalizing the city’s civic core were undertaken. The Beaux-Arts Public Library was revived with the addition of the Modernist Eastman Reading Garden (1960) designed by George Creed, and in 1964 the nearby Cleveland Mall’s northern and central sections were updated by the landscape architecture and engineering firm, Clarke & Rapuano to allow for the construction of a convention center beneath. Seeking to reorient the city towards the lakefront, I. M. Pei & Associates’ 1961 Erieview plan was approved, which called for clearing more than 150 acres of the downtown business district to make room for new office buildings, hotels, and housing. Partially realized in sporadic efforts that continued into the 1980s, the plan resulted in the construction of several structures, including the Erieview Tower (1964), though many lots stood vacant for years.

During this time, African Americans continued to experience discrimination. In the Hough neighborhood, where the African American population had grown by 70% between 1950 and 1960, federally funded urban renewal programs cleared vast swaths of the neighborhood without providing replacement housing for those displaced. Hoping to protect residential areas of the Glenville neighborhood, city councilman Leo Jackson proposed a more community-led approach to urban renewal in 1964, but eruptions of racial tension, including a series of 1966 East Side riots that burned a historic pedestrian bridge (Sidaway Bridge) and a shootout between Cleveland Police and a Black Nationalist group in 1968, prevented his Glenville Plan from being implemented.

Birth of the Preservation Movement

In the 1960s and 1970s, following years of heavy industrial activity, geographic upheaval, and urban renewal, Clevelanders mobilized to protect the city’s built and natural environment. In 1966, a coalition of civic organizations and garden clubs successfully thwarted the construction of a freeway through several African American neighborhoods and the parks and lakes of Shaker Heights, eventually creating the Nature Center at Shaker Lakes in its proposed path. Three years later, in June of 1969, an oil slick on the Cuyahoga River caught fire, confirming the growing national concern about the pollution of Lake Erie and the rivers pouring into it, and spurring the U.S. Congress to adopt the Clean Water Act of 1972 and the National Environmental Policy Act later that year.

Local nonprofits also formed to save Cleveland’s historic and cultural landmarks from demolition, among them the Playhouse Square Association, the Cleveland Landmarks Commission, and the Downtown Restoration Society (now Cleveland Restoration Society).

Modern Revitalization Efforts

The late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries have reinvigorated Cleveland’s civic and public realm. In 1995, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Museum designed by I. M. Pei & Associates opened, anchoring the city’s lakefront and spurring tourism. Further waterfront development continues today with a new plan to energize the landscape surrounding the Hall of Fame, led by Practice for Architecture and Urbanism and James Corner Field Operations.

In recent years, many of Cleveland’s once-neglected areas have been revitalized, programmed, and made more pedestrian-friendly. New riverfront trails have improved connections to nearby cultural and natural resources, including the Ohio and Erie Canalway National Heritage Area and Cuyahoga Valley National Park. Downtown, the 1930s-era Eastman Reading Garden at the Cleveland Public Library, rehabilitated by Hanna/Olin Landscape Architects in 1998, is enlivened by rotating public art commissioned by LAND Studio. The Modernist Ralph J. Perk Plaza was rehabilitated by Thomas Balsley Associates with Jim McKnight in 2012, and the historic Public Square was transformed by James Corner Field Operations in 2016. In University Circle, the Nord Family Greenway, designed by Sasaki and completed in 2018, enhances connectivity in University Circle with new parkland traversing through Wade Park.

In the twenty-first century, Cleveland’s tradition of patronage has evolved in creative partnership with federal, state and local entities, often spearheaded by community-led groups that are investing and stewarding a more inclusive civic public realm; from parks, plazas, and gardens to commemorative landscapes, commercial corridors, and residential streets.

Cleveland has been the witness to hundreds of years of economic, demographic, and cultural change, and the city’s unique collection of cultural landscapes offers a portal to those sometimes-invisible cultural lifeways of the past that also serve as a foundation for its ambitious vision for the city’s future.