Arapahoe Acres Design Intent Threatened by Unsympathetic Renovations

During the late 1940s, Edward Hawkins had a vision to develop a community of contemporary homes in Denver’s burgeoning post-war housing market. A tract of farmland south of the University of Denver, then the hinterlands of the city, became Arapahoe Acres. Today, the neighborhood of low-slung roofed homes and curvilinear streets topped by a mature tree canopy continues to be a unique enclave in the Denver suburbs. However, cumulative changes to the designed landscape now threaten the community’s consistent planned aesthetic.

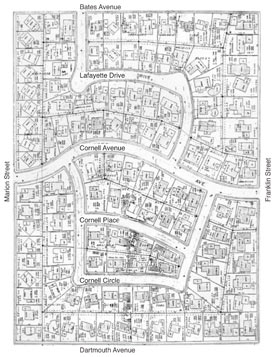

Arapahoe Acres Site PlanHistory

During the late 1940s, Edward Hawkins had a vision to develop a community of contemporary homes in Denver’s burgeoning post-war housing market. A tract of farmland south of the University of Denver, then the hinterlands of the city, became Arapahoe Acres. Hawkins hired Eugene Sternberg, a Czechoslovakian architect, to design the site plan and, subsequently, the first home in the tract. In total, 124 homes were constructed between 1949 and 1957. Of those 20 are directly attributable to Sternberg, five are by other architects, and the remainder were designed by Hawkins. The homes reflect both Hawkins’ interest in Usonian architecture and Sternberg’s European influence, the International style. This combination of flat and low-slung roofed homes along with the curvilinear streetscape created a truly unique place in the south Denver suburbs, one, that for the most part, remained unaltered until recently.

The site design for the development utilized the naturally rolling topography of the plains to sculpt the streets and define the home sites. Bounded on the perimeter by metropolitan Denver’s strict grid of streets, interior streets break the grid to distinguish the area from surrounding neighborhoods. Curvilinear streets and closed loops focus views of the mountains and create enclosed vistas that highlight the houses. Homes sited along the primary interior street, Cornell Avenue, direct the view to the west around a curve to reveal the snow-covered peak of Mount Evans on the horizon. Narrow concrete walks flank broad streets and define public and private spaces.

Lot sizes and shapes vary. Smaller properties on the perimeter are often only 5000 square feet while those on the interior are generally larger and, in a few cases, reach nearly half an acre. Homes are set back with broad front lawns which slope according to the natural topography and are planted with specimen trees and shrubs. Though its mature tree canopy is not indigenous to the high, arid environment of the northern plains, original owners planted the now large trees that today shade the lush enclave. In their shadow, the expansive lots flank the streets to create a park-like setting that encourages neighbors to chat, walkers to linger, and children to play.

(upper) Homes on South Cornell Circle; (lower) East Cornell

AvenueOutdoor living, popularized during this time by such landscape architects as Thomas Dolliver Church and Garrett Eckbo is emphasized; many of the homes have back patios and original custom-built detailing, including planters and walls of a harmonious design; and outdoor lighting incorporated into the home designs. Hawkins with the aid of landscape contracter Roy Woodman, was responsible for landscape design in the community’s public areas as well as the design for many of the individual lots. In the 1960s, Stanley K. Yoshimura and Hylam Shimoda were commissioned to design Japanese Style gardens for a number of homes. These gardens showcase natural stone, evergreen plantings and the use of water in the landscape.

The streetscape and houses were designed to take full advantage of natural views of the surrounding mountains and neighborhood, and plantings are intentionally situated to provide framed views of the setting. Locally produced brick, lodgepole pine, and concrete block were used extensively in the design of both the homes and landscape features. Brick and block bearing walls support large expanses of glass, which allow sunlight to bathe into interior spaces. Low slung roofs create vaulted interiors. Thru-wall louvers and clearstory windows provide ventilation. Millwork, window walls, and interior paneling were built on site in the woodshop.

To guide growth and manage change, Hawkins established covenants for Arapahoe Acres. These defined land use, lot size, building footprints, setbacks, and other design aspects including the review of all landscape materials over four feet tall. They also required the election of a Neighborhood Board and appointment of an Architectural Control Committee. The covenants are perpetual unless voted otherwise by homeowners. During his time in residence, Hawkins served as both. However, neither a Board nor an Architectural Control Committee has been in convened since Hawkins left Arapahoe Acres in 1967.

For much of the first fifty years of occupancy, the relationship of the street to the residential lots remained unaltered, which maintained the unique character of the neighborhood. In the early 1990s, many of the original owners began to leave the neighborhood and new residents, including many artists and architects seeking out Mid-Century Modern architecture, moved in. These new owners strove to maintain or renovate sympathetically. As home prices accelerated in the next decade, incoming residents made more significant changes to the properties, altering the landscape, architectural details and character defining features of the individual homes. While many of these renovations were well intentioned, the accumulation of changes both to the homes and to the landscape threatened the original design intentions of the neighborhood as a whole.

In 1997, Arapahoe Acres became the first post-World War II neighborhood listed in the National Register of Historic Places. In the same year, Historic Denver published a walking tour of the neighborhood. The neighborhood was recently featured in a local Denver magazine, 5280, as one of the best places in Denver to live. The article states “it might be the metro area’s most distinct neighborhood” and calls it “the most arresting and unusual setting south Denver has to offer,” even though it is in Englewood. Visiting architects seek it out, tour buses occasionally drive through, not-for-profits host home tours, and carloads of tourists drive slowly along the streets snapping photos. The neighborhood represents a snapshot in time and records the exuberance of the post-World War II era for experimentation and enthusiasm for distinctive residential architecture in a prosperous country.

Threat

While Arapahoe Acres continues to garner praise and attention for its important design, growth and change are inevitable. Lots are large enough that expansions of existing homes are possible. And, as the city’s population grows in number and affluence, this becomes more of a consideration. Also, the homes are now fifty years old and comparatively inefficient in many ways; renovation and maintenance are necessary.

Arapahoe Acres had a very limited plant palette historically. The bluegrass lawns provided a unifying sweep of green along the streets. Today, the simple lawns are being removed and replaced with extensive plantings. By disrupting the green ribbon along the street, continuity is lost between parcels. New landscape designs often incorporate new approaches and the original concrete walks are lost to more complex building materials. Finally, as homes expand, fence lines have been pushed toward the street which diminishes the character of the streetscape by limiting historic viewsheds to “borrowed” mountain scenery. Mature trees are often removed during new construction and often go unreplaced. The cumulative effects of such changes can create a very different and often inconsistent design aesthetic within the community, eroding historic visual and spatial relationships as well as significant material fabric.

Get Involved

For several years, a small contingent of Arapahoe Acres homeowners has sought to organize the neighborhood, build community ties, and manage growth. It is important however, that individual homeowners learn more about the historic significance of the community so that any renovations that they make are sympathetic with the original design intent. A wealth of resources is available to homeowners that can enable them to improve their homes and not sacrifice the character defining features. It is important for residents to understand how such good stewardship practice not only benefits the whole community, but, in doing so, can help raise and protect property values long term.

From coast to coast, post-war designed communities from Radburn, New Jersey, to Baldwin Hills Village, Los Angeles, California, are grappling with the same issues today. Historic preservation and sustainable design are not mutually exclusive. As the first National Register listed post-war community, Arapahoe Acres has the opportunity to lead the field recognizing the important role that preservation plays in sustainable design. Individual homeowners can learn more about the historic significance of the community so that any renovations that they make are sympathetic with the original design intent. A wealth of resources is available to homeowners that can enable them to improve their homes and not sacrifice character defining features. Reengaging the architectural review committee that would provide guidance based on existing historic research with the goal of balancing both historic preservation and sustainability values would provide homeowners with another resource for protecting their investment and their distinctive community. It is important for residents to understand how such good stewardship practice not only benefits the whole community, but, in doing so, can help raise and protect property values long term.

Resources

National Trust for Historic Preservation: Sustainability and Preservation

Arapahoe Acres; History Design Vocabulary Preservation Guide by Diane Wray

The Arapahoe Acres Historic District by Diane Wray

Images courtesy of the author.