Plans to Erase Pershing Park Encounter Roadblocks

Pershing Park, Washington, D.C. Photo © Brian Thomson

On November 19, 2015, representatives of the U.S. World War I Centennial Commission appeared before the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts (CFA) to present the five finalist designs for a new World War I memorial in a redeveloped Pershing Park. Located on Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C., the park was commissioned by the Pennsylvania Avenue Development Corporation (PADC) and completed in 1981. The plan to redevelop the park is controversial, because the park was designed by leading modernist landscape architect M. Paul Friedberg with a planting plan by Oehme, van Sweden & Associates, the firm responsible for the celebrated style known as the “New American Garden.” In response to the design competition, TCLF listed Pershing as a Landslide site earlier this year.

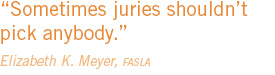

Liza Gilbert immediately asked who would bear responsibility for maintaining the site—the answer: the National Park Service. It was a pointed question, given that Pershing Park’s current dilapidated state is owed to years of deferred maintenance by the National Park Service, making it particularly vulnerable as a candidate for redevelopment. Commission member Alex Krieger took exception to a basic premise of the design competition itself, asking why “a park that happens to contain a memorial” (as the current Pershing Park is disparagingly described on the memorial competition’s website) is a bad thing. “Sometimes juries shouldn’t pick anybody,” said Elizabeth K. Meyer, conveying frustration with the fact that all of the finalists’ submissions would erase Friedberg’s design and would treat the park in isolation, ignoring the larger context of the work of the PADC.

Pershing Park. Photo © Brian Thomson

Pershing Park. Photo © Brian Thomson

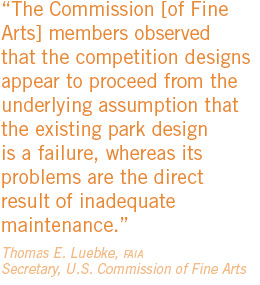

On November 30, Thomas Luebke, the secretary of the CFA, described the upshot of the presentation in an official letter to Robert Vogel, director of the National Park Service’s National Capital Region:

...[the Commission members] commented that the presented competition designs generally treat Pershing Park as an isolated site, when in fact this park has been central to the Pennsylvania Avenue Development Corporation’s transformation of the corridor linking the White House and the U.S. Capitol into a compelling visual symbol of the American democracy. They expressed concern that the designs are excessively focused on completely reinventing the existing site without addressing the park’s outstanding characteristics and vital role within a series of symbolic urban spaces.

The Commission members observed that the competition designs appear to proceed from the underlying assumption that the existing park design is a failure, whereas its problems are the direct result of inadequate maintenance. They commented that many features of the park—such as the berms and other topographical elements which help create a sheltered space at the center of the park and which are eliminated in most of these schemes—are the very characteristics of the design that make the existing park an appropriate setting for a contemplative memorial. Thus, they criticized the competition program for understating the value and importance of the existing park design, and they encouraged conceiving of the project as a new memorial within an existing park.

After the CFA’s public admonitions, an article published in the Washington City Paper speculated that the design competition had been sent “back to the drawing board.”

The World War I Centennial Commission next appeared before the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC) on December 3, 2015, where Fountain and Lewis, as they had before the CFA, introduced the design competition and presented the five finalist designs. Lewis concluded with a statement explicitly declaring his opinion that Friedberg’s design for Pershing Park was a failure. While Lewis’ statement put him at odds with the collective wisdom of the American Society of Landscape Architects (which awarded Friedberg its Design Medal and its ASLA Medal, making him one of only six practitioners to receive both awards in the ASLA’s 116-year history), it did not put the issue of the park’s historic design to rest. Indeed, the strongest reaction to the five finalists' designs at the NCPC meeting was, once again, negative: “The five designs we are looking at obliterate the Friedberg design,” observed NCPC member Beth White.

The World War I Centennial Commission next appeared before the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC) on December 3, 2015, where Fountain and Lewis, as they had before the CFA, introduced the design competition and presented the five finalist designs. Lewis concluded with a statement explicitly declaring his opinion that Friedberg’s design for Pershing Park was a failure. While Lewis’ statement put him at odds with the collective wisdom of the American Society of Landscape Architects (which awarded Friedberg its Design Medal and its ASLA Medal, making him one of only six practitioners to receive both awards in the ASLA’s 116-year history), it did not put the issue of the park’s historic design to rest. Indeed, the strongest reaction to the five finalists' designs at the NCPC meeting was, once again, negative: “The five designs we are looking at obliterate the Friedberg design,” observed NCPC member Beth White.

While the scrutiny of the CFA and the NCPC was clearly a setback to the plans of the World War I Memorial Design Competition, it can and should be viewed as an opportunity to incorporate measured and consequential advice into the competition as the process goes forward. And because no winning design for the site can be finalized until a Determination of Eligibility (due in July 2016) dictates whether Pershing Park is eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places, there is ample time to translate that advice into a design that appropriately recognizes the history, context, and importance of the park itself.

A successful World War I memorial need neither be so complex nor so large as to overpower the existing park; it would, in fact, rather profit from working with Friedberg’s design intent to achieve something of beauty and significance. It is perhaps ironic, but instructive, to remember other words from the design competition manager Roger Lewis, who, in 2010, wrote the following in the Washington Post regarding the proposed Frank Gehry-designed Eisenhower memorial: “… creating an inspiring memorial does not necessitate building something vast, grandiose or bristling with an excess of elements. A simple yet memorable design idea, beautifully uniting landscape and structure, can be very powerful.”

Pershing Park. Photo © Brian Thomson