Designing Tomorrow: America’s World’s Fairs of the 1930s

Editor’s note: This special feature is being posted in concert with the National Building Museum’s exhibition Designing Tomorrow: America’s World Fairs of the 1930s and to highlight the addition of several Exhibition Grounds profiles in the What’s Out There database.

In the midst of the Great Depression, tens of millions of visitors flocked to world’s fairs in Chicago, San Diego, Cleveland, Dallas, San Francisco, and New York where they encountered visions of a modern, technological tomorrow unlike anything seen before.

Eager for projects at a time when little new construction was being financed, participating designers built-out the fairgrounds with eclectic architecture and landscape that was often placed within traditional Beaux-Arts site plans. Like their predecessors, the Depression Era campuses were most often designed on cleared or undeveloped land, incorporating buildings, courtyards, gardens, and art, mounted by the Federal government, states, and foreign nations. A central component at each of these fairs were their pavilions, which housed innovative and dynamic exhibitions that paid tribute to topics as diverse as factory production, technology, and speed. The result was a golden vision of the future during one of the country’s worst economic decades.

Exhibits at these fairs forecasted the houses and cities of tomorrow and presented streamlined trains, modern furnishings, and even talking robots. Architects and industrial designers like Raymond Loewy, Norman Bel Geddes, Henry Dreyfuss, and Walter Dorwin Teague collaborated with businesses like General Motors and Westinghouse to present a visionary future complete with highways, televisions, and all-electric kitchens. New York Fair’s Futurama display designed by Norman Bel Geddes for General Motors took fairgoers on a narrated trip across a 35,000-square-foot model of an imagined metropolis and its surrounding countryside. Leading corporations and the Federal government used the fairs as laboratories for experimenting with innovative display and public relations techniques, and as grand platforms for the introduction of new products and ideas to the American public.

(upper) The Alcazar Gardens, Balboa Park, San Diego;

(lower) Brazilia Pavilion by Thomas Price, New York

World’s Fair.

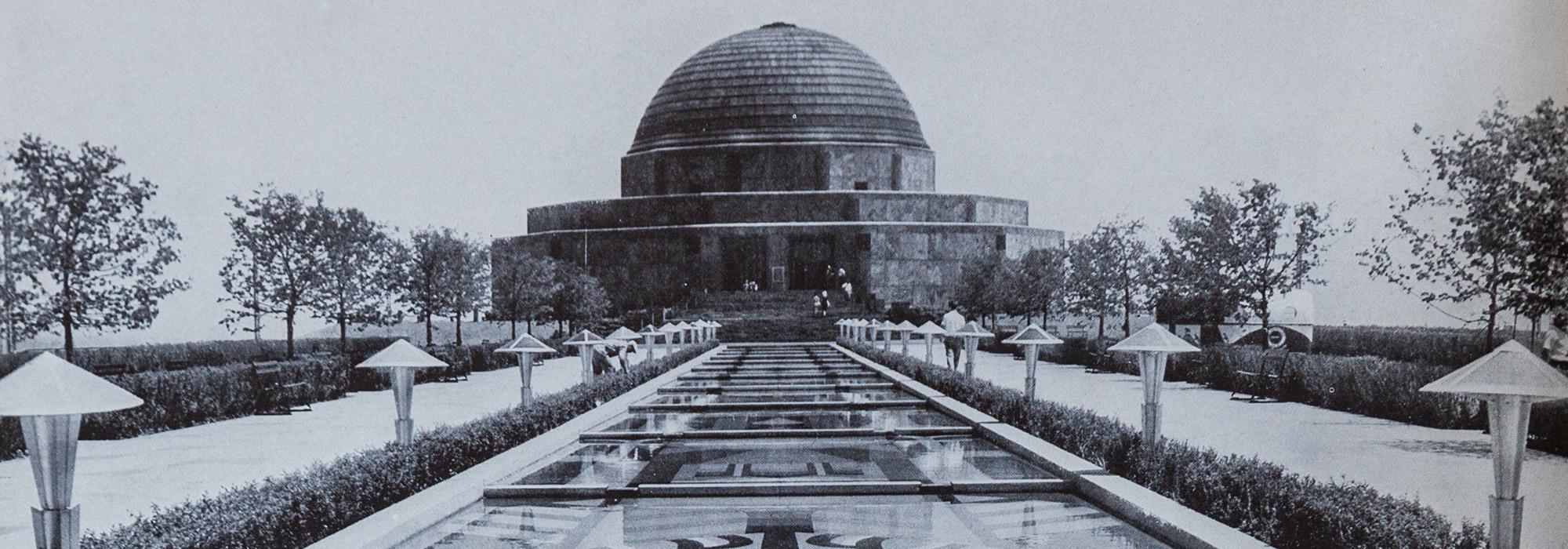

The fairs also introduced visitors to new ways of thinking about public space and the character of their home environments. Landscape architect Ferrucchio Vitale and and Austrian architect Joseph Urban held joint responsibility for landscape design, site planning, and construction of Chicago’s “A Century of Progress” fair, which was conceived as the extension of Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr. and Daniel H. Burnham's concept for the World’s Columbian Exposition held 40 years earlier. Vitale and Urban’s plans for the site and landscape design were only partially executed, due to the illness and death of both designers before the fair opened. Richard Requa’s design for the outdoor environment in San Diego showcased the potential for grand civic spaces adjacent to residential-scale places, such as the Alcazar Gardens, in the context of exotic Hispano-Moorish-inspired design.

The construction and design of the fairs themselves illustrated innovations in land development and building technologies. San Francisco’s fair celebrated the completion of two remarkable structural feats – the Golden Gate and San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridges – and was sited on Treasure Island, created from 25 million cubic feet of San Francisco Bay dredge materials. Before the New York Worlds Fair was ever constructed, it was record-breaking as the largest land reclamation project ever undertaken in the eastern U.S. The fair was situated on 1216-acre “Corona Dumps” in Flushing Meadows, Queens, a primeval bog loaded with ashes and debris that required almost one million cubic yards of excavation and soil shifting. The New York fair was notable for its inclusion of a host of reputable landscape architects and planners, including Gilmore Clarke, Michael Rapuano, Paul Cret, Jacques Gréber, Clarence Stein, Charles Downing Lay, Alfred Geiffert, Jr., Nellie B. Allen, Harold Caparn, Thomas Price, A. F. Brinckerhoff, C. N. Lowrie, and Jay Downer.

While many of the fair sites have been demolished or heavily altered, several have survived as important cultural and civic spaces. The Prado pedestrian plaza, its buildings, and several gardens from the California Pacific International Exposition remain a vital center of activity in San Diego’s Balboa Park. Leased to the U.S. Navy from World War II until 1996, the remaining buildings and site plan on Treasure Island in San Francisco are now part of a mixed-use master plan for the Island’s redevelopment. Through continued use and thoughtful management, Dallas’s Fair Park represents the most intact collection of 1930s exposition planning, fair buildings and public art in the country. Learn more about these extant exposition grounds in the What’s Out There profiles for the Dallas, San Diego, and San Francisco fairs.

The fairs foretold much of what would become modern post-war America—from the national highway system to glass-walled skyscrapers and the spread of suburbia. The exhibition Designing Tomorrow: America’s World Fairs of the 1930s, on display through September 5, 2011, at the National Building Museum in Washington, D.C., explores the impact of America’s Depression-Era world’s fairs on the popularization of modern design and the creation of a modern consumer culture. Learn more about the exhibit at nbm.org

Resources

Designing Tomorrow, September 2010. Edited by Robert W. Rydell, and Laura Burd Schiavo, Yale University Press.