It Takes One: Peggy King Jorde

Peggy King Jorde is a cultural projects consultant combining more than 30 years of experience in architecture and historic preservation projects in New York City and beyond. King Jorde served under three NYC mayors, providing comprehensive oversight of all capital construction projects specific to New York’s cultural landmarks, public art, and art museums.

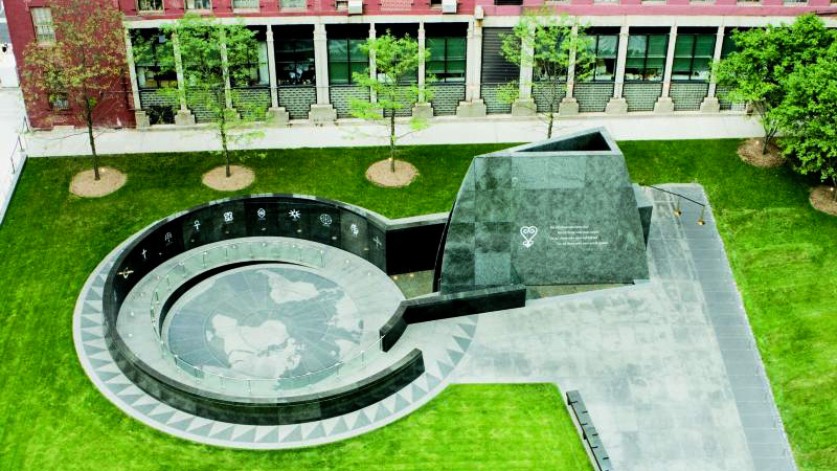

King Jorde took the lead in advocating and shepherding the creation of New York’s African Burial Ground National Monument and Interpretive Center. She is also an advocate for the preservation of the African burial ground discovered on Saint Helena Island, an important marker of the Middle Passage of the transatlantic slave trade, located midway between Africa and the New World on the routes used by slave traders.

Please explain the meaning of this sentence on your website: "It matters how we choose to remember."

As we live and breathe, so we remember. How we remember our forebears matters because their lives and legacy matter. We are their "unfinished business"; therefore, how we interpret, reclaim, and convey the humanity they were denied under chattel slavery determines how their legacy will fuel future generations.

Tell us about your childhood in Albany, Georgia; key memories and moments; how it affected your personal and professional growth.

I am a descendant of enslaved African people, the legacy of a global crime. I was born during the American apartheid, in the basement of a segregated hospital in Albany, Georgia. I was raised the daughter of a Civil Rights lawyer who defended Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and a courageous mother who was an educator and community organizer in her own right.

In 1964 my parents sent me to desegregate a first-grade class at an all-white public elementary school. I remember being called by many names for the first two years of attending school, but rarely by my birth name. One schoolmate who occasionally demonstrated some civility towards me still could not overcome the boundaries of race, referring to me as “Lil' Nig.”

Two years before desegregating that public school, my father was caned and bloodied by a local sheriff for trying to visit his client, a white Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) demonstrator, in jail. The image of my father bandaged and blood-soaked was legendary and appeared in the New York Times. My mother wasn't exempt from racial terrorism either. My father was often away working on cases in other towns, leaving Mom home alone with my brothers and me. One night, an uncle dropped by unexpectedly while my mother sat sewing in my room. Almost as abruptly as he entered, he exited, leaving my mother cradling nervously a crumpled brown package. She immediately distanced herself from it, placing it at the far end of my dresser. Later, I woke up to find her sitting with lights out, silhouetted in my bedroom window, cigarette in hand keeping a vigil throughout the night. Threats of racial violence were real, and I would later learn that the brown package concealed a gun. Our home was our fortress, but white aggressors could breach our communities unapologetically and often without consequence.

Reflecting upon these experiences and the significance of historical and cultural landscapes, I am reminded how remarkable it was to acquire my first library card. The Andrew Carnegie Public Library in my hometown was built in 1906, but Blacks were prohibited from access. By 1962, after protests and desegregation, the library closed its doors. A year later, it reopened with all the chairs removed. Shortly after that, at age five or six, my mother took me to apply for my first library card. I will never forget the experience and Mom ensured that the significance of the occasion was not lost on me. The story around what it took for my community and me to enjoy the same rights and privileges as other Americans is absent despite the library being placed on the National Register of Historic Places by the U.S. Department of Interior. There is so much work to be done.

In 1990 you became a pivotal figure in the future of a seventeenth-century African Burial Ground discovered at the construction site of a federal building in lower Manhattan (in New York City). There was a point at which a job assignment became a calling; what happened?

Government authorities issued a gag order prohibiting workers from sharing details about preliminary archaeological excavations underway at a federal construction site two blocks north of City Hall Park. The New York Landmarks Preservation Commission office invited me to join a small group to visit the construction site. At the time, I was working in the Mayor's Office of Construction, providing oversight of capital construction projects for New York's museums and cultural institutions. I had reviewed the maps and read the recommendations by experts advising the federal agency to proceed with caution and consider the potential for unearthing cultural materials that could provide significant insight into the lives of New York's African population.

As I stood curbside, listening to the archaeologist deflect and minimize inquiries from the group, I experienced personal outrage. I could not help reflecting upon my late father's Civil Rights legacy to our community. I remembered the sacrifices and contributions of countless people who helped shape our community and me.

Yet, upon the order of a United States government agency, a contractor was attempting to render irrelevant and ultimately erase the memory, lives, and history unfolding at a burial ground for enslaved and free Africans. This was about my community, my history and it mattered who would tell their story.

Do you consider yourself an activist, and why?

Activism is defined as work that employs actions to bring about political or social change. Employing actions for change is consistent with my work, mainly where it concerns marginalized communities. My job requires me to engage in various forms of activism which might include a groundswell of direct strategic action to bring about change. Whether within the walls of city hall, at the boardroom table, in a community center, or on the street, I work with various stakeholders to help secure cultural and historical integrity on memorialization projects.

Consider the current climate in the highest reaches of government aiming to block the teaching of African American history. Regrettably, the preservation of African American cultural heritage is seen as a threat, grossly under represented, and relegated to the margins of society. The course of my work can sometimes recall the plight of a "Repo Man."

The work can be contentious, calling for the reclamation of an asset in possession of others who don't understand that "ownership" was never theirs to begin with and that there remains an outstanding debt of reparative justice.

Who are the people – past and present – who inspire you, whom you admire, who are your personal touchstones, and why?

My parents were my North Star. What I learned from them in community service is at the heart of how I perform my work in preservation.

Their work was rooted in activism and service. Challenging and reshaping historical narratives, devoting my time and insights to support, engage and empower stakeholders without a voice, and bringing about awareness and facilitating collaborations for the common good. At the end of my father's life, he asked that his children build his coffin by hand, and so I did with one of my brothers. For my brother and me, it was in the spirit of service, remembrance, and respect.

A personal touchstone? The moment my career pivoted from a project planner in the NYC Mayor's Office of Construction to cultural heritage protection. My friend, the late Harry Wurster, an NYC Department of Parks employee for City Hall Park, had an insatiable appetite for N.Y. history. In a meeting over a bag lunch, he wanted to make me aware of a burial ground for enslaved and free Africans. Harry garnered the 1990 copy of the environmental impact statement (EIS) for the Foley Square federal courthouse and office building. The extensive historical research within the pages of the EIS revealed a little-known history of slavery in New York. His persistence and my passion would ultimately precipitate my navigating the ranks of City Hall to help redirect the fate of this sacred site.

What are you currently working on?

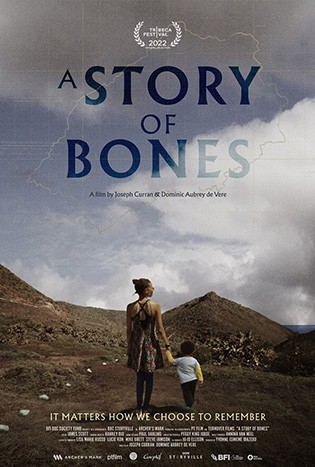

I am a Consulting Producer and a participant in the British documentary A Story of Bones. In 2018, I visited a burial site on the island of St. Helena (where Napoleon was interred), a British overseas territory located in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is host to approximately ten thousand enslaved Africans retrieved from the hulls of slave ships bound for the Americas. Three hundred twenty-five human remains were unearthed during the construction of an airport service road and stored in a prison facility for over a decade. Annina van Neel, a woman from Namibia who was involved in the construction project, campaigned to create a respectful burial ground for reinterring the remains. While on the island, which was part of the Middle Passage, I met with the community and shared insights learned from the New York African Burial Ground preservation. After my return Stateside, I invited Ms. van Neel to visit the New York site and to join me on a road trip through the American South to gain greater insight about the legacies of slavery. From New York, we traveled to Montgomery, Alabama, and Albany and Savannah, Georgia, and Charleston and St. Helena Island, South Carolina. The documentary is our call to action, heightening global awareness around the need for memorialization.

A Story of Bones premiered in June 2022 at the Tribeca Film Festival in NYC, marking our impact campaign's launch. The burial ground is considered one of the most significant traces of the Middle Passage and the slave trade.

The similarities between the struggle on St. Helena and Sint Eustatius prompted an alliance. Following my work with St. Helena, I joined a dynamic group of activists and community organizers who formed the Sint Eustatius Afrikan Burial Ground Alliance. I accepted the invitation in October to serve on the Statia Cultural Heritage Implementation Committee (SCHIC). The committee will engage the descendant community and experts to develop best practices appropriately memorializing burial grounds and the reinternment of ancestral remains on the Dutch Caribbean island of Sint Eustatius.

Rarely in my experience has a developer willingly taken on a burial ground preservation project. I am the project consultant for the housing developer and nonprofit organization Bowery Residents Committee (BRC). BRC advanced plans to purchase a lot on Tenth Avenue between 212th Street and 211th Street in northern Manhattan in Inwood to build and operate a high-quality shelter for people experiencing homelessness. The site was an auto repair shop. Research about the site's history revealed that it was part of a cemetery for enslaved African people, adjoined by an Indigenous Lenape ceremonial area dating earlier. In 1903, as the neighborhood developed, city work crews unearthed the human remains of nearly forty enslaved individuals who were dishonored and discarded and removed several Lenape ceremonial pits. Rather than walk away from the site, BRC embraced the historical significance and extensive community engagement and committed to preserving its historical integrity even if it could not develop it as planned. There is no recognition of the site's history or acknowledgment of those previously buried.

The architectural team of Elizabeth Kennedy, Mark Gardner, and Chris Cornelius will develop a place for reflection, reburial, and memorial and be responsive to the recommendations of the descendant community.

Lastly, I am a consulting producer for a documentary in production by Heather Quinlin and Caroline DeVoe about The Cherry Lane Cemetery on Staten Island, New York.

The burial site for hundreds of enslaved and free Africans is now a strip mall, and records indicate that the human remains were never moved from the area before development. The Staten Island descendants of Benjamin Prine, the last known formerly enslaved man buried at the site, are fighting to preserve their ancestors' memory and the site's cultural integrity.

What does success (if that is the appropriate word) look like in your work?

The "bedrock" of my work is building a groundswell of community stakeholders to help guide memorialization and engage descendants in meaningful and productive ways. Community engagement throughout my memory work is critical to cultivating, distilling, and conveying the cultural and historical truths and narratives most vital to them.

Please define cultural landscape.

I believe human involvement has affected, influenced, and shaped cultural landscapes. Interpreting the influences of human involvement is where integrity and legacy meet.