Baltimore's Landscape Legacy

The What’s Out There Cultural Landscapes Guide to Baltimore is the fifth in an ongoing series of guides being produced in a collaboration between The Cultural Landscape Foundation (TCLF) and the National Park Service (NPS). The series launched in March of 2016 with a guide to Philadelphia, followed later that year by one to New York City. The Boston guide was published in 2017, followed by a guide to Richmond, Virginia.

Land patents for the current site of Baltimore City were first issued to English colonists in 1660 by proprietor Cecil Calvert, the second Lord Baltimore. By 1670 a small settlement had developed that included a jailhouse, courthouse, and rudimentary roads. By 1715 Baltimore County had reached a population of 3,000, although fewer than 800 residents were considered “masters and taxable men.” Despite suffering persecution under the Maryland colonial assembly, Quaker communities also settled in the area along the Patapsco River and Great Falls. The region’s first religious structure and cemetery were established by the Friend’s Community in 1713 as the Friendship Burial Ground.

It was the economic growth from the grain and iron markets that finally resulted in the establishment of Baltimore City. Flour mills and iron forgeries, backed by wealthy planter families, were established along both Gwynns and Jones Falls. Investor and planter Charles Carroll (the Barrister) bought tracts of land in the surrounding area for iron-ore development, including a plantation that became his estate, Mount Clare, now Carroll Park. Charles Ridgely, Jr., established an iron forgery on the Gunpowder River that ran through his 1,500 acre Hampton estate in 1760. By 1783 the plantation owner had accrued enough income from iron and grain production to build the Georgian mansion that now serves as the centerpiece of the Hampton National Historic Site.

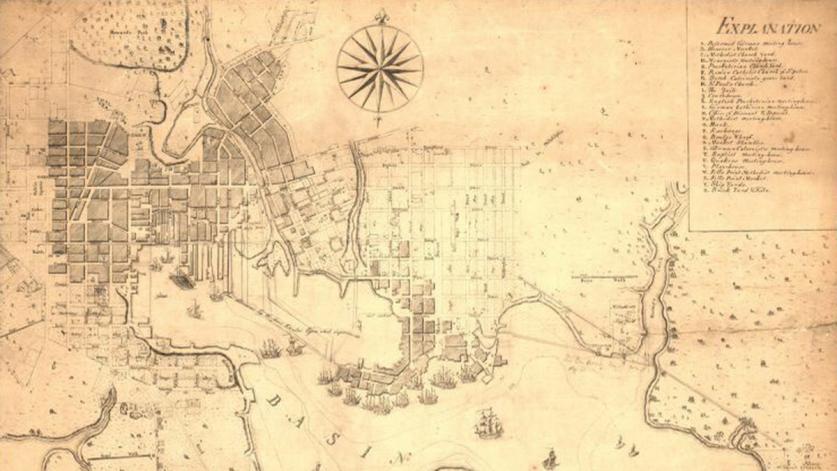

What is today the City of Baltimore traces its roots to three early settlements: Baltimore Town, established in 1730 on the north side of the Patapsco River’s inner basin, consisted of 60 one-acre lots situated between a harbor to the south and woodlands to the north; Jones Town, laid out on a ten-acre plot directly east of Jones Falls in 1732; and Fells Point, established in 1761 by English Quaker William Fell along the harbor of the Patapsco River, less than a mile southeast of Jones Town. Jones Town and Fells Point were annexed by Baltimore Town in 1745 and 1773, respectively.

Baltimore Town developed rapidly as a result of a series of wars that unfolded in the latter half of the eighteenth century. Conflict between France and England, from 1756 to 1806, proved advantageous to Baltimore merchants who exploited disruptions in European shipping. The city grew in population as refugee communities seeking safety and opportunity settled in the area. Among these immigrants were some 900 people expelled from Nova Scotia, who formed Baltimore’s first Catholic Parish in what is now known as the Cathedral Hill Historic District. Scottish and German immigrants experienced in milling eventually invested capital in waterfront properties, where they built wharves extending more than 1,000 feet into the Patapsco River. The development of the town was also marked by the establishment of essential amenities, including cemeteries, such as the Old Western Burying Ground (now called Westminster Hall and Burying Ground), founded in 1786 one mile beyond the town’s boundaries.

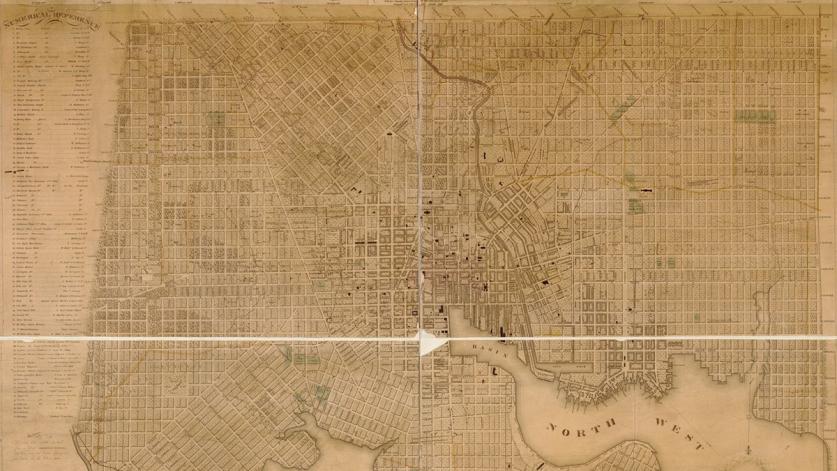

At the dawn of the nineteenth century, Baltimore’s economy shifted decisively towards manufacturing. The establishment of cotton and powder factories along the Patapsco River and Jones Falls attracted new waves of laborers who formed neighborhoods centered near sites of industry, including Federal Hill. In 1812 Baltimore’s Board of Commissioners contracted surveyor Thomas Poppelton to map the city and create a plan for its future development. He designed a socially stratified gridiron pattern comprising main streets, side streets, and small alleys. This urban plan influenced the development of districts such as Mount Vernon Place, where large lots on main streets were planned for wealthy merchants, while smaller row houses, intended for the middle class and laborers, were constructed on secondary streets and in alleyways.

The city had also become substantially fortified during this period as a result of its strategic location along the Patapsco River. Fort McHenry, located at the end of Locust Point, famously withstood an attack by the British during the Battle of Baltimore in 1814 (part of the War of 1812). During this same conflict, privateers based at Fell's Point, sailing in fast clipper ships, launched attacks against the British forces. These and other actions eventually provoked the British to attack by land and sea. Baltimore strengthened its land-based defenses, including building defensive earthworks at Hampstead Hill, located within what is now Patterson Park. By 1816 the population of Baltimore had reached 45,000, requiring the town to expand its boundaries from three to ten square miles.

In addition to improvements in the city’s infrastructure, Baltimoreans also invested in creating cultural and social institutions. It was the creation of commemorative landscapes such as Robert Mill’s Mount Vernon Place, the site of Baltimore's Washington Monument, completed in 1829 and considered to be nation’s first monument to George Washington, and the Maximillian Godfrey’s Battle Monument, the nation’s first war significant memorial, finished in 1825, that would earn Baltimore the nickname “The Monumental City.”

In 1827 Baltimore merchants applied to the Maryland legislature for the incorporation of a joint-stock company called the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. Baltimore’s resulting railway industry expanded over the succeeding generations, transforming the previously undeveloped southern peninsula into an industrial node where railways met shipyards. Communities of laborers formed thriving neighborhoods, such as Locust Point and Union Square, around these centers of industry. It was also in this period that entrepreneur William Freemen developed the city’s first suburb (now the Franklintown Historic District), in 1831, along the Franklin Turnpike, offering Baltimoreans an alternative to the dense urban landscape.

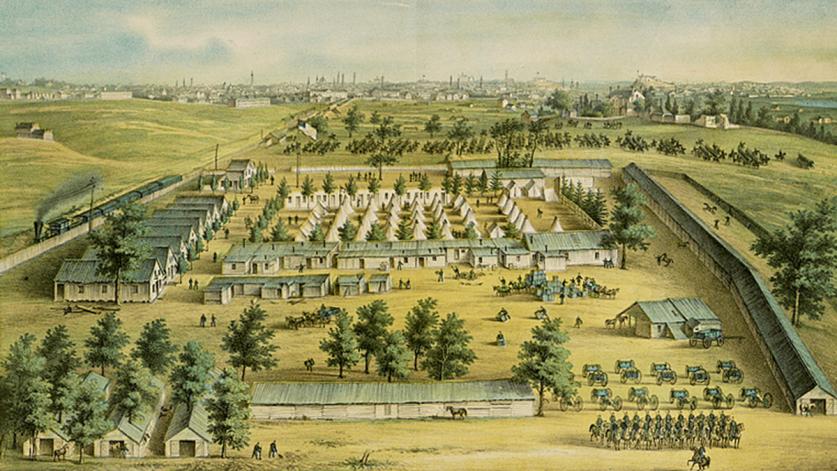

As the divided nation entered the throes of the Civil War, Baltimore’s harbor and railway systems guaranteed that the city would serve as a critical transportation hub during the conflict. The war also left its mark on the landscape in other ways. Patterson Park was transformed for military use, becoming a Union encampment, as were the grounds of the Mount Clare Estate, located in what is today Carroll Park. Fort McHenry was converted into a prison camp, while additional fortifications were built upon Federal Hill. The mortality rate experienced in the city’s hospitals necessitated the creation of new burial grounds, including the Loudon National Cemetery, established five miles west of the municipal boundaries.

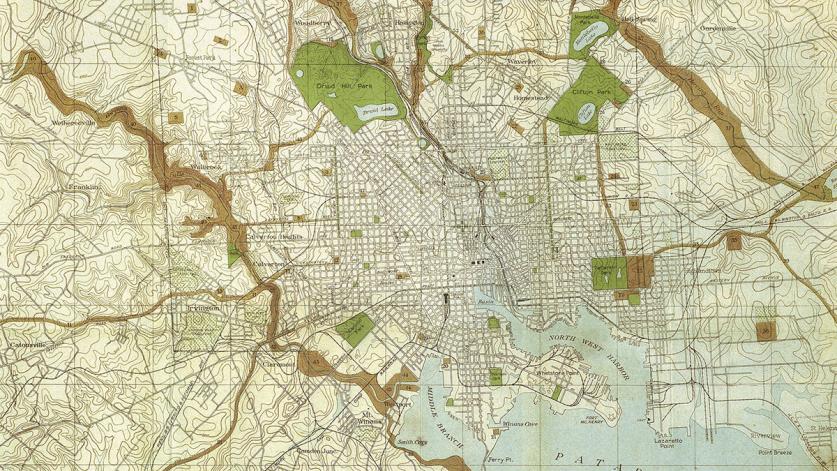

Beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, reformers, concerned about the potential adverse effects of industrialization on both physical and mental health, pushed for the creation of several Baltimore parks. In 1860 landscape gardener Howard Daniels designed the 745-acre Druid Hill Park from the former estate of Lloyd Nicholas Rogers. Patterson Park, originally created in 1827, was expanded and improved both before and after the War. Mount Vernon Place, long neglected, was redesigned by Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., in 1875. From 1890 to 1917, city leaders transformed the former plantation estates of Charles Carroll the Barrister and Johns Hopkins into two of Baltimore's premier recreational spaces, Carroll Park and Clifton Park, respectivley.

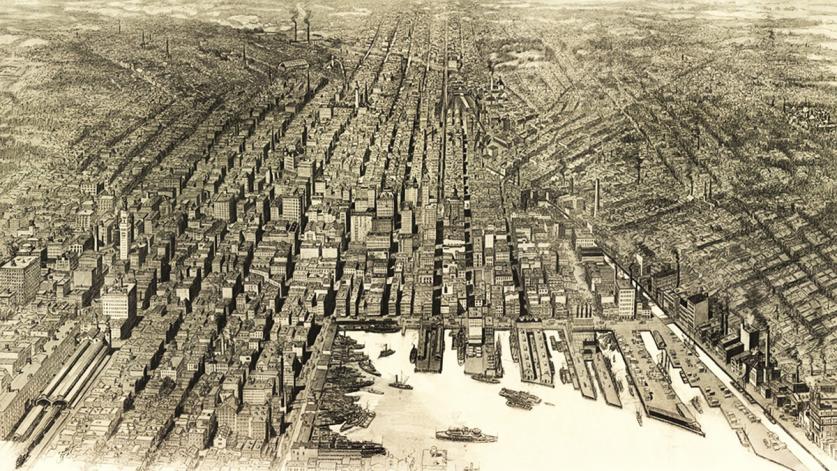

From 1850 to the turn of the twentieth century, Baltimore’s population exploded, growing from 169,000 to 508,000 in 50 years. The change in demographics forced Baltimore to annex a series of affluent suburbs, together known as “The Belt,” increasing the city’s size from ten to 30 square miles. By 1900 more than 100 suburban villages encircled the urban center. As Jewish families and other European minorities gained wealth and success, they migrated from east Baltimore to the northwest suburbs where they formed more spacious neighborhoods, including Park Circle. Longstanding institutions also sought opportunities to relocate. Johns Hopkins University moved to it is current location in 1918, leaving its campus on the former estate of Charles Carroll, Jr., northwest of the city.

Following the 1888 annexation, city officials realized that Thomas Poppleton’s original city plan could no longer suffice as a guide to urban growth. Baltimore’s Municipal Art Society was formed in 1889, conceived as an institution that would work to beautify the city and help guide its long-term expansion. The society, in collaboration with the Parks Board, began acquiring acreage to create parks in and around Baltimore, including Latrobe and Wyman Park in 1902 (the latter to include what is now known as Wyman Park Dell). That same year the Society hired the Olmsted Brothers firm to draw up a new city plan. The firm’s 1904 Report Upon the Development of Public Grounds for Baltimore called for the creation of a system of parkways and stream valley reserves that would link together the city’s major parks providing inhabitants more recreational space while encouraging conscientious city planning. Throughout the early twentieth century, the city’s Park Board sought to implement the designs proposed by the Olmsted Brothers plan, developing three parkways: Gwynns Falls Parkway, The Alameda, and 33rd Street Boulevard, as well as new recreation spaces in Wyman and Leakin Parks.

In the same year that the Olmsted report was published, a fire destroyed downtown Baltimore, burning through 140 acres and razing 1,526 buildings before being extinguished at Jones Falls. In the aftermath, many residents and industries fled to neighborhoods north of the Inner Harbor, permanently transforming residential communities such as Cathedral Hill into commercial districts. Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., aided in the rebuilding process by providing recommendations on how the city could improve the downtown’s existing design. His suggestions focused primarily on widening streets that served as major thoroughfares or that were located near the waterfront. Following his direction, city planners widened twelve streets, including Pratt Street, Charles Street, and Lombard Street.

Increased population growth between 1910 and 1918 forced the Municipal Art Society to annex more northern suburbs in 1918, increasing the city’s boundaries from 30 to 92 square miles. By 1939 the northeastern suburbs had grown from just 279 housing lots to more than 14,000. Some of the more prominent suburbs were Greater Homeland (1924) and Guilford (1913)—both developed by Edward Bouton of the Lake Roland Park Company, who had initiated the creation of Roland Park in 1890, one of the nation’s earliest garden suburbs, located in northwest Baltimore. Development increased following World War II, as veterans relocated outside the city to start families. Industry and commercialism followed the migration, creating industrial parks and shopping centers along highway systems. The increase in commercial development along major thoroughfares like U.S. Route 1, connecting Baltimore to Washington, D.C, led the National Park Service (in conjunction with the U.S. Bureau of Public Roads) to create the limited-access Baltimore-Washington Parkway in 1947 as a more efficient and scenic alternative. Notably, Baltimore’s African American population, having grown substantially as result of the Great Migration (beginning in 1916), was largely excluded from suburbanization due to racist policies established by state and municipal governments, real estate corporations, and housing developments. As a result, the majority African Americans resided in high-density, urban housing east, west and south of the downtown commercial district. As the White population moved out, African American communities relocated to the formerly prohibited White neighborhoods, moving progressively west past Fulton Avenue.

By 1959 Baltimoreans had formed the Greater Baltimore Committee in hopes of revitalizing the city center. In cooperation with city officials, this committee published a report advocating for the renewal of a 22-acre space in downtown Baltimore, ultimately including the Charles Center complex and its three new plazas.

Following the success of Charles Center, the Philadelphia-based firm Wallace, McHarg, Roberts and Todd was contracted to redevelop Baltimore’s Inner Harbor. Their design plan featured a harbor surrounded by public space connected via a waterfront promenade. The 240 acres surrounding the Inner Harbor were leveled to make way for new roads, parks, and piers. One of the first features to be installed was a brick promenade extending from Federal Hill to Fells Point. Over the years, public landscapes, including McKeldin Square and Rash Field, were developed in a further effort to transform the Inner Harbor into a popular tourist destination.

The 1980s saw the emergence of a nationwide park renaissance. In Baltimore there was a push for the revitalization of some of the city’s most significant historic designed landscapes, garnering them renewed visibility. In 1985 a nationwide design competition was held for the improvement of Druid Hill Park, followed by revisions made to Carroll Park in 1987 and Patterson Park in 1998. In 1987 civic and community leaders collaborated with the American Society of Landscape Architects to produce a revitalization plan for Wyman Park Drive and the 33rd Street Corridor. This was followed by the republication of the Olmsted Brothers 1904 Plan by the newly founded Friends of Maryland’s Olmsted Parks & Landscapes, Inc., marking the first time an Olmsted Brothers plan for a municipal park and boulevard system was reprinted for a contemporary audience.

In 2013 the office of Mayor Stephanie Rawings-Blake released “Inner Harbor 2.0,” a revitalization plan developed by Waterfront Partnership and the Greater Baltimore Committee. This plan’s objective is to ensure the Inner Harbor’s future economic viability by repairing aging infrastructure and creating new recreational spaces.

The historical significance of many of Baltimore’s cultural landscapes was officially recognized in 2009, when the U.S. Congress designated 22 square miles within the city as a National Heritage Area. The area is centered on the historical neighborhoods and parks that proved instrumental to the city’s development. Other designated landscapes include Federal Hill, Druid Hill and Carroll Parks, Westminster Burying Ground, Mount Vernon Place, Johns Hopkins University, and Center Plaza.