Boston's Landscape Legacy

The What’s Out There Cultural Landscapes Guide to Boston is the third in an ongoing series of guides being produced in a collaboration between The Cultural Landscape Foundation (TCLF) and the National Park Service (NPS). The series launched in March of 2016 with a guide to Philadelphia followed later that year by one to New York City. This guide moves deeper into the northeast region and examines the multi-layered history of Boston’s physical development, from its founding as a colonial seaport, through the consequential “Big Dig” at the turn of the 21st century.

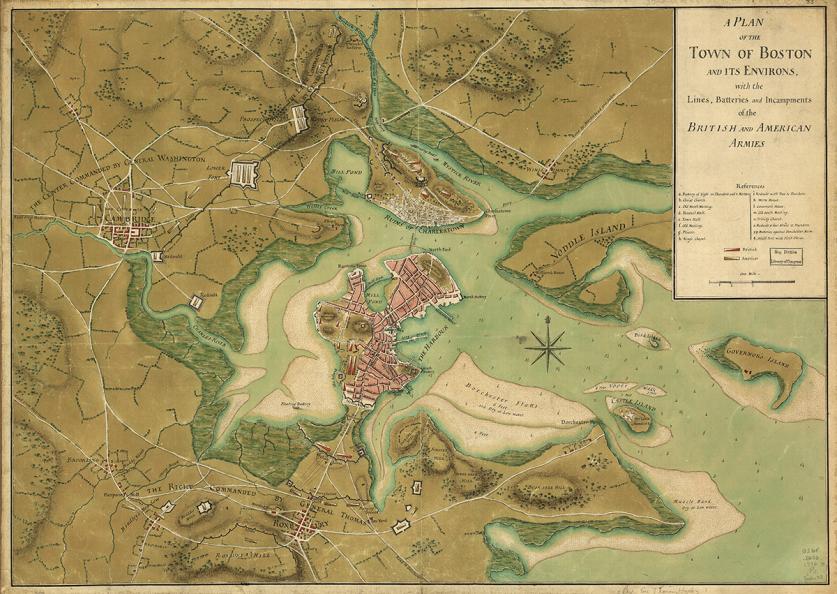

The Massachusetts Bay Colony was formally established in 1628, after Puritan settlers located a freshwater spring on the Boston peninsula. Topography was the peninsula’s dominant feature, comprising three hills connected to the mainland by a narrow strip of beach. Colonists settled on Beacon Hill, one of the steep hills overlooking Massachusetts Bay. The peak offered strategic views of the Charles River estuary and Boston Harbor, and was relatively safe from tidal flooding.

During colonial times, Boston grew into an active seaport with a bustling Common (historically, the Public Common) established at the foot of Beacon Hill for public cattle grazing. The western shores of the peninsula remained largely uninhabited, with the exception of the occasional small farm, while the portside began to develop a pre-industrial urban character. But it was not until after America’s Revolutionary War in 1776 that the city we know today truly began to take shape. In the decades following the Revolutionary War, connectivity with Charlestown and Cambridge was established via bridges, and the town of Boston began to shed its provincial character. Boston finally incorporated as a city in 1822- almost two centuries after its founding as a town.

Boston’s population increased dramatically during the nineteenth century, as the harbor developed into a leading commercial hub. It became a center for trading in sugar, salt, fish, and tobacco. Immigrants played a large role in the population growth of the city, many of them arriving from Ireland. They settled in the city’s established neighborhoods, such as the North End and Fort Hill, while more prosperous residents relocated to the newly built Back Bay and South Boston neighborhoods. Infrastructure improvements were undertaken in the form of roads and sewers.

As the harbor increased in use, manufacturing emerged as the primary land-based industry in the region. The network of rivers flowing into the harbor facilitated the transportation of goods throughout New England, where mills and factories proliferated. An active public market (Faneuil Hall) was built near the harbor in 1742 to accommodate the growing number of merchants, and expanded by architect Charles Bulfinch in 1806. An investment in railroads during the 1850s further increased the expansion of infrastructure beyond the immediate city. During the 1880s streetcar lines established linkages to adjacent residential suburbs, such as Brookline.

Although slavery had already been abolished in Massachusetts in 1783, an abolitionist community was active in Boston during the early nineteenth century. William Lloyd Garrison, whose home was located in the nearby town of Roxbury, founded The Liberator, an anti-slavery newsletter, in 1831. The publication called for complete emancipation across the United States and gained a large following. Boston became a destination for those hoping to escape from slavery. Many emancipated African Americans lived on the north slope of Beacon Hill, which led to one of the highest concentrations of black-owned properties in the United States before the Civil War (several of which are featured along the Black Heritage Trail).

Growth in educational opportunities occurred alongside industrial development in Boston. Just across the Charles River in Cambridge, Harvard University began to take its modern form through the installation of lawns and pathways at Harvard Yard in the early nineteenth century. The first American medical school to train women, the New England Female Medical College, opened in Boston in 1848, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) opened its first campus in Boston in 1865 (before moving across the river to Cambridge in 1916). The region became known as a center for literary and intellectual thought. The Transcendentalist and Boston Brahmin movements flourished, and attracted progressive intellectuals such as: Nathaniel Hawthorne, who wrote the book The Blithedale Romance about his stay at Brook Farm; a Transcendentalist commune in West Roxbury; the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (whose former residence in Cambridge is managed by the NPS); and author Ralph Waldo Emerson. Walden Pond, to the northwest of Boston, became famous as the location for Henry David Thoreau’s reflection and writings on nature.

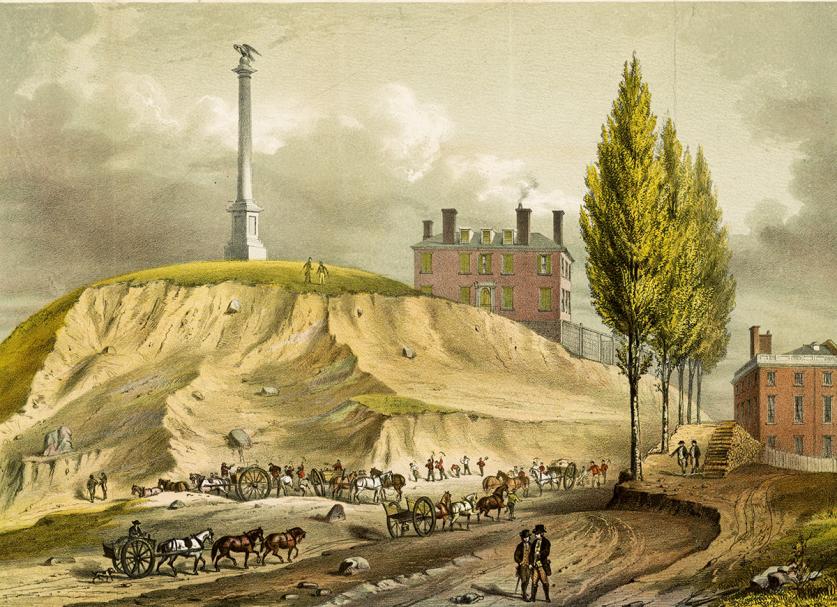

All the while, Boston’s physical boundaries continued to expand. Several adjacent towns were annexed during the late nineteenth century, including Roxbury and Dorchester. The growth of the city, both in terms of population and land reclamation/annexation, was not cohesively planned. Little thought was put into public spaces or parks until the establishment of the Boston Park Commission in 1875, and the Metropolitan Park Commission in 1893. The former created parks within the city, while the latter created the nation’s first system of parks on a regional scale.

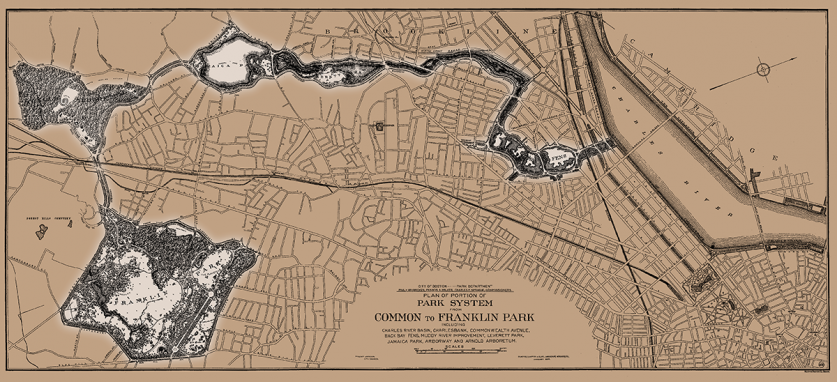

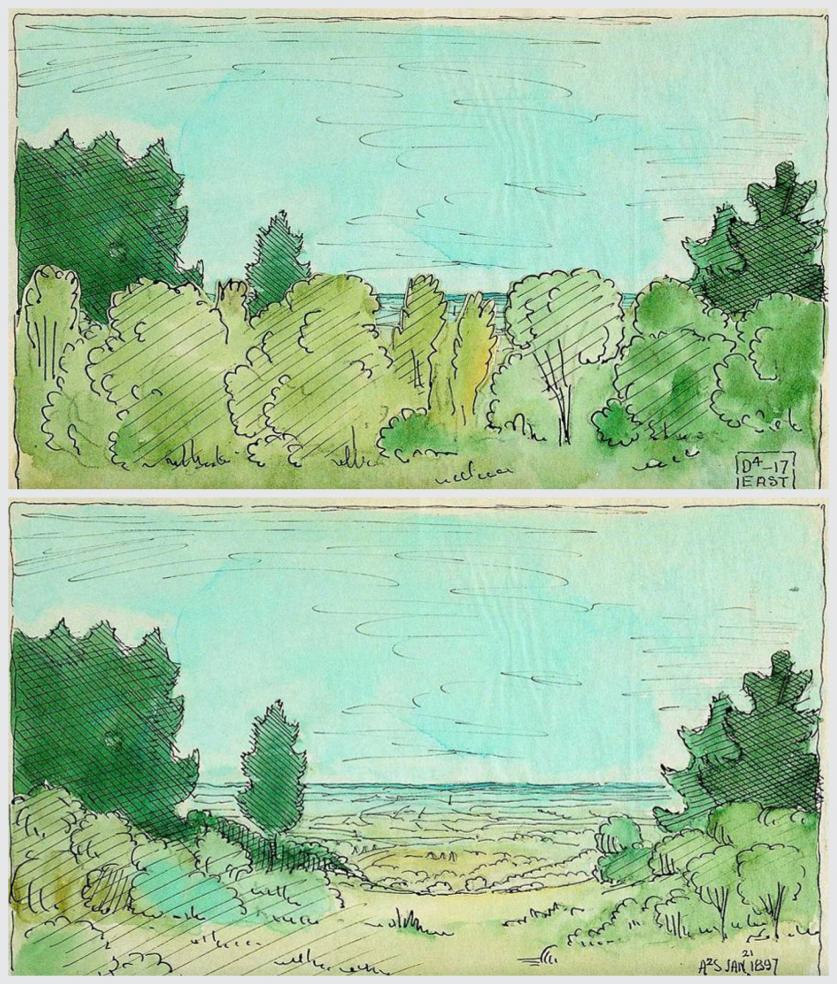

Between 1878 and 1895, the Boston Park Commission initiated the construction of more than 2,000 acres of publicly accessible parkland. Conceived and implemented by landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., the design stretches from the Common at the foot of the State House in downtown Boston all the way to the southern limits of the city, and set a precedent for public park systems and urban greenways in America and beyond. What has come to be known as the Emerald Necklace consisted of five new parks, including Back Bay Fens, Muddy River Improvement (now known as the Riverway and Olmsted Park), Jamaica Park, Arnold Arboretum, and Franklin Park, which built upon existing green spaces such as the Commonwealth Avenue Mall, the Public Garden, and the Common. Under continued guidance of the Olmsted firm in various iterations, additional parks were incorporated into the Emerald Necklace, such as Marine Park and the Chestnut Hill Reservoir at the western terminus of Commonwealth Avenue. The Boston Park Commission continues today as the Boston Parks and Recreation Commission.

In addition to the Emerald Necklace, the introduction of the Metropolitan Park Commission is perhaps the most significant development in the history of the region’s public parks. In 1890 landscape architect Charles Eliot published an article in Garden and Forest in which he discussed the importance of preserving assets to be held in public trust. That year he formed the Trustees of Public Reservations (now the Trustees of Reservations), the initial step toward the formation of a metropolitan park system. A temporary commission was formed in 1892, which was led by Eliot and Sylvester Baxter. The following year the Metropolitan Park Commission was established, and it began to acquire such sites as Beaver Brook Reservation (1893), Blue Hills Reservation (1893), and Revere Beach Reservation (1895). Eliot formally joined forces with Olmsted, Sr., by becoming a partner in Olmsted, Olmsted & Eliot in 1893, and as a result, the firm was appointed as landscape architects to the Commission. By the end of 1895, thousands of acres of forest reservations, coastal beaches, and riverbanks had been acquired. Many of the sites are now listed in the National Register for Historic Places. In 1919, the Metropolitan Park Commission was renamed the Metropolitan District Commission, which was dissolved in 2003. The newly formed Department of Conservation and Recreation assumed the former commission’s responsibilities.

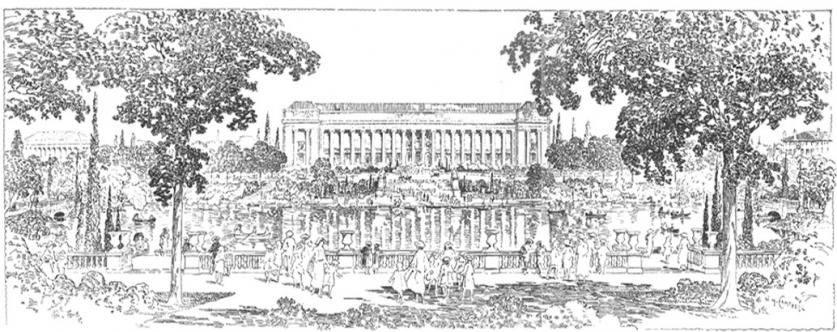

By the turn of the twentieth century, the physical size of Boston had dramatically expanded from its time as a colonial seaport. Eliot and Olmsted’s vision for adopting a comprehensive planning strategy for the city’s growth was accompanied by a contemporary fervor for the City Beautiful movement, an urban beautification philosophy that was popularized in North America by the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. The movement adapted Beaux-Arts and Garden City principles with the goal of influencing social issues through urban design and civic pride. Several important institutions were constructed during this time, including the Boston Public Library building and courtyard designed by McKim, Mead & White in 1895, and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts designed by Guy Lowell in 1909. In the Back Bay Fens, additions to the southern basin (namely the Kelleher Rose Garden and ball fields) that responded to Lowell’s City Beautiful building were designed by Arthur Shurcliff (who also designed parts of the Franklin Park Zoo, Paul Revere Mall, and expansions to the Charles River Esplanade during this period). When MIT’s new campus was dedicated in 1916, architect William Welles Bosworth had incorporated City Beautiful concepts to design a Neoclassical entrance court containing a grand lawn leading to a domed library building.

In the 1930s an underwater automobile tunnel was built to connect the North End neighborhood with East Boston, a former island in Massachusetts Bay. In 1938 the first public housing project was constructed in the South Boston neighborhood. Growth began to slow down after World War II, and many mills in the region were shuttered. The city adopted a philosophy towards urban renewal, aimed at combatting the economic downturn. Several residential neighborhoods faced full-scale demolition, and thousands of residents were displaced in the name of encouraging new industry. In 1953 the Columbia Point public housing projects were completed in Dorchester on 50 acres of land. In 1956 a raised interstate was constructed through the center of Boston’s downtown, effectively cutting the waterfront (the city’s economic center) and South Station off from the rest of the city. Several proposed extensions during the 1960s and 1970s were dropped in the face of growing public outcry. Meanwhile, other projects, such as the residential complex at Columbia Point, were deteriorating due to neglect.

Concurrent with the rise of redevelopment was a heightened public desire to recognize the role Boston played in the Revolutionary War. Dedicated in 1951, the Freedom Trail memorializes more than a dozen sites with strong associations to events that occurred leading up to or during the war. This resulted in increased levels of civic pride, renewed patriotism and even a few early historic preservation successes, ultimately leading to the establishment of the Boston National Historical Park in 1974. Perhaps one of the most well-traveled urban parks in America, the Boston National Historical Park comprises many of the cultural landscapes connected via the Freedom Trail.

While urban renewal is generally looked upon as a failure, it did make way for several Modernist projects in Boston where landscape architects played a significant role. These include the Brutalist Government Center Urban Renewal Plan, featuring City Hall Plaza, completed by I.M. Pei & Associates in 1968, with Sasaki, Dawson & DeMay as associated landscape architects; Copley Square, redesigned in 1970 and demolished in 1991; and, the 25-acre master plan by I.M. Pei & Associates for the Christian Science Center in the Back Bay, completed in 1971 in collaboration with the Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA). It is worth noting that these projects were all completed in concert with Sasaki, Dawson & DeMay, the firm that also designed Christopher Columbus Waterfront Park, which was unveiled on the Bicentennial on July 4, 1976, and Long Wharf, which opened in 1979.

The Sasaki office and the BRA were not alone in their quest to revitalize the city. Interest surged in the public, private, and ultimately non-profit sectors to restore and rehabilitate the city’s historic and cultural heritage. In addition to the Christopher Columbus Waterfront Park, to mark the bicentennial of the Revolutionary War, Boston reinvested in the city’s historic sites and established several new waterfront parks. In the early 1980s the Columbia Point complex was sold to a private developer, and both the buildings and landscape became the subject of multiple revitalization efforts led by Goody, Clancy & Associates along with Carol R. Johnson Associates landscape architects. Parks also saw increased attention during this period, with rehabilitation master plans undertaken for the Common and the Public Garden. Under the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Management’s Olmsted Historic Landscape Preservation Program in 1984, an unprecedented twelve parks (including the Emerald Necklace and Franklin Park) were the beneficiaries of twelve million dollars in funds.

Building on Bostonians’ interest and commitment to parks and open space, in 2007 a decades-long project to bury the elevated highway (nicknamed the “Big Dig”) was completed, and some of the city’s oldest neighborhoods re-established their connectivity to the waterfront. The Rose Kennedy Greenway opened in 2008, formed from a linear collection of parks that followed the path of the elevated highway. Almost 400 years after the founding of the town of Boston, the waterfront remains the heart of the city.