About Houston

“…and when the rich lands of this country shall be settled, a trade will flow to it, making it, beyond all doubt, the great interior commercial emporium of Texas.”

-from an advertisement for “The Town of Houston” in the Telegraph and Texas Register, August 30, 1836

The What’s Out There Houston Guide from The Cultural Landscape Foundation (TCLF) outlines the design and stewardship of the fourth largest city in the United States. From the town’s founding on the swampy ground at the confluence of Buffalo Bayou and White Oak Bayou to its growth as the world’s largest center of refineries and petrochemical plants, the story of Houston’s transformation can be read in the history of its natural and designed landscapes.

This profusely illustrated interactive Guide has grown out of TCLF’s ever-expanding What’s Out There program, a free digital database that makes visible the designed landscapes in our midst. Currently featuring 1,900 landscapes, 900 designer biographies, and 10,000 images, What’s Out There—and this Guide—are connected to TCLF’s What’s Nearby, a GPS-enabled function that locates all sites in the database within a 25-mile/40-kilometer radius of any given location.

This What’s Out There Houston Guide includes illustrated profiles of more than 40 landscapes and nearly 30 designers—and it will continue to evolve as TCLF expands the reach of its documentation efforts in Houston and throughout the American Southwest. Contemporary photos of each site illustrate the unique qualities of Houston’s distinctive landscapes, from Picturesque to Postmodernist. These accompany original, detailed descriptions of a wide array of landscapes, including arboretums, boulevards, campuses, cemeteries, commemorative landscapes, garden estates, institutional grounds, plazas, parks, roof gardens, suburbs, and waterfront developments. An extensive essay complemented by historic photographs and maps provides information about the chronological development of Houston’s legacy of landscapes and urban form.

Invaluable support for the development of the What’s Out There Houston Guide was provided by Bartlett Tree Experts, Design Workshop, the Houston Parks Board, SWA Group, Uptown Houston, and Victor Stanley (a complete list of sponsors can be found here). The launching of the Guide in March 2016 coincides with TCLF’s Leading with Landscape II: The Houston Transformation conference and the What’s Out There Weekend Houston, the latter comprising free, expert-led tours of nearly 40 sites over the course of two days. We hope you will find this Guide a useful and compelling resource, one that will inspire you to explore the “Bayou City.”

FROM ITS BEGINNING TO 1900

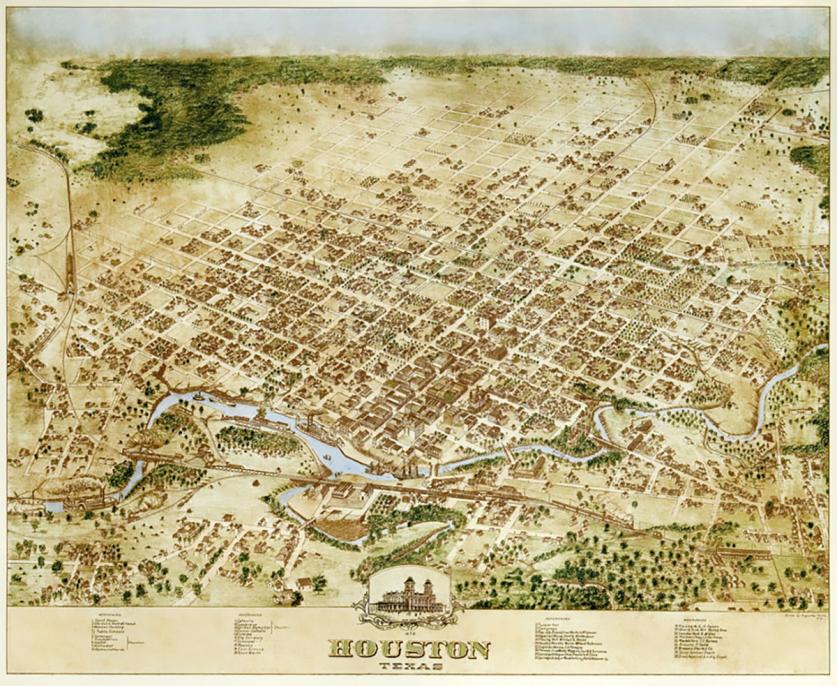

In 1836, Augustus and John Allen purchased more than 6,000 swampy acres along the southern bank of Buffalo Bayou from the estate of John Austin and officially established the Town of Houston one year later. Entrepreneurs at best and real estate hucksters at worst, the Allen brothers sited their town some fifty miles inland from the port of Galveston, at the confluence of Buffalo Bayou and White Oak Bayou, two of the many slow-moving tidal rivers that patiently drain the flat coastal plain. The crossing of Main Street and Congress Street divided the 1836 plan into four wards (with two additional wards created by 1876), and an 1838 survey by S.P. Hollingsworth further divided the western part of downtown Houston (including what is now known as the Old Sixth Ward) into long, narrow lots, which quickly began to sell. By 1841, the first City Hall was built in Market Square at the site of the town’s founding, which became Market Square Park in 1976 (a contributing feature of the Main Street/Market Square Historic District, listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1983).

The emancipation of slavery was announced in Texas on June 19th, 1865, two years after it had been declared by President Abraham Lincoln. Soon after, many formerly enslaved people migrated to Houston from throughout Texas and Louisiana and formed a community west of downtown. It eventually expanded to encompass 90 city blocks, reaching all the way to Buffalo Bayou, and became known as Freedmen's Town.

In the thirty years after Houston’s founding, nearly constant epidemics of yellow fever and annual bouts of cholera ravaged the town. Still, by 1870, Houston had become a major rail terminus and distribution center, bringing timber and cotton from the interior of the vast territory to wider markets reached via barges and riverboats headed downstream to the Gulf of Mexico. In 1871, the state legislature issued a charter to the Houston Cemetery Company for Glenwood Cemetery, a park-like rural cemetery established one mile west of downtown. By 1873, the Houston City Railway Company, then serving a town of over 9,000 residents, had extended a line across Buffalo Bayou to connect with the cemetery.

An 1873 map by Augustus Koch shows the town with two public schools, a synagogue, and at least ten churches of various denominations, two of which, on Travis Street and Rusk Street, were labeled “colored.” Antioch Missionary Baptist Church, built in 1875, was among the earliest brick structures in the city to be built and owned by African Americans. Located in the historic Fourth Ward, the church was listed in the National Register of historic Places in 1976, and SWA Group created a Modernist design for a parcel to its east called Antioch Park in the 1980s. Located nearby on a parcel acquired by the city in 2009 is Bethel Park, designed to evoke the structure of Bethel Missionary Baptist Church, originally built on the site in 1891. The Reverend John Henry Yates, who was born into slavery and later helped establish the congregations of both Antioch and Bethel, is buried in nearby College Memorial Park Cemetery, one of the oldest African American burial grounds in Houston. In 1899, the town added its first park to the list of civic amenities: City Park (later renamed Sam Houston Park) was a Victorian Gardenesque design that included a lake and bandstand. Since the 1950s, the city has relocated nine historic structures to the park, which also serves as the setting for many commemorative monuments.

FROM 1900 TO WWII

A new age began on January 10, 1901, when oil gushed from the ground at Spindletop Hill in Beaumont Texas, just east of Houston. The ensuing economic boom would fundamentally change Texas—and Houston in particular, which would eventually be home to more refineries and petrochemical plants than any other city in the world. After a hurricane devastated Galveston in 1900 (followed by another in 1915), highlighting the vulnerability of its coastal location, capital investment flowed inland to Houston, better protected by its distance from the sea. The dredging of Buffalo Bayou in 1914 to create the Houston Ship Channel allowed ocean-going vessels to reach Houston for the first time, vastly increasing the commercial capacity of its port, which, within 30 years, ranked third in the nation in the tonnage it transferred.

The rapid growth of Houston spurred efforts to establish a plan for its expansion. The city’s first comprehensive plan was presented to the Houston Parks Commission in 1913 by Massachusetts-based landscape architect and planner Arthur Comey. Although Comey’s plans were not implemented, the Houston Parks and Recreation Department was created in 1916 to provide oversight for two extant parcels—the 20-acre Sam Houston Park and the 445-acre Hermann Park. The latter occupied land donated to the city in 1914 along the banks of Brays Bayou and was designed initially by George Kessler and, later, by Hare & Hare.

The city’s early expansion beyond the downtown core included not only parkland, but also residential suburban enclaves. The Broadacres neighborhood was developed in the mid-1920s and included roads with grassy medians and allées of live oaks. In 1924, Will and Michael Hogg, along with Hugh Porter, developed the River Oaks neighborhood, which subsequently drew attention to the stretch of Buffalo Bayou that connected it to Houston’s downtown. City engineer J.C. McVea had already reported in 1921 that many of Houston’s shortcomings arose from the fact that no agency was responsible for reviewing the city’s development, resulting in an absence of zoning and unified planning. Stepping in to fill the breach (with what later parlance would surely describe as a public-private partnership) was Will Hogg, who privately purchased 1,503 acres along the northern bank of Buffalo Bayou in 1924 and sold it to the city at a favorable price to create what would become Memorial Park. Hogg even lent the city $50,000 to make the initial payments on the parcel, and he also secured land that would become Buffalo Bayou Park and the downtown Civic Center. In 1929, Hare & Hare submitted a comprehensive planning document to the City Planning Commission, but the requisite ordinances failed and the Commission was disbanded, one in a succession of such commissions (the first established in 1922) that routinely foundered for lack of political support.

And yet the need for comprehensive planning during this period is readily evinced by the fact that during the 1930s, Houston’s population soared, from 292,352 to 384,514 at the end of the decade. In 1940, Ralph Ellifrit was chosen to head the newly established Department of City Planning. During his 23-year tenure, he worked with S. Herbert Hare (the city’s professional planning consultant until his death in 1960) to revise the 1929 plan for Houston’s parks and major thoroughfares. Ellifrit oversaw the westward expansion of the Brays Bayou Parkway and the creation of the White Oak Bayou Parkway. But what would prove to be even more impactful, he was chiefly responsible for initially planning Houston’s network of freeways. Designed by William James Van London, who was appointed the engineer-manager for Houston in 1945, the freeway system was innovative in its segregation of road traffic from railways and cross-traffic via the widespread use of overpasses.

FROM WWII TO PRESENT

In the wake of World War II, Houston emerged as a leading manufacturing and refining center, whose population would sharply increase in the years to come. The city also expanded its territory dramatically, annexing surrounding area in large amounts in the 1940s and again in the 1950s. Three-quarters of what is today the City of Houston has been built since 1945. Referenda to establish zoning laws were placed before Houston voters in 1948, 1962, and 1993, and all were rejected. The combination of rapid, decentralized development and a lack of zoning meant that Houston’s freeways have in essence guided its growth, as housing in various forms was planted on vacant land along freeway routes, which were also a driving force behind annexation. The first section of the Gulf Freeway, Houston’s first freeway, opened in September 1948, reaching Galveston by 1952. With plentiful land and few natural barriers to expansion, it has always been cheaper for Houston to sprawl than to climb, which is why the city covers more ground—over 660 square miles—than any other in the United States.

The 1960s saw the arrival of NASA in Houston, and the Arab Oil Embargo of 1973 sent capital streaming into the city, as the demand for Texas oil skyrocketed. During this time, attention began to shift slowly from the city’s roadways to its parks and its 2,500 miles of waterways. In the early 1970s, Charles Tapley began the development of what would become the 6.3-mile-long Buffalo Bayou Park, which, with the work of SWA Group in 2012, is now 160 acres of expansive views, trails, hikes, riparian habitat, and naturalistic landscapes. Comey had recommended reserving sections of Buffalo Bayou and White Oak Bayou for parks and parkways in his 1913 report. Today, White Oak Bayou Greenway comprises pedestrian and bicycle paths that, once complete, will create fifteen miles of linear greenspace. Landscape architects at SWA Group and Clark Condon have worked on various segments of the greenway. A conceptual plan for the Menil Collection Campus in Houston’s Montrose neighborhood was developed in 1970 by Louis Khan and Harriet Pattison. Although the plan was not realized, it nonetheless represented an early attempt to knit together a Houston neighborhood with landscape as the connective tissue.

Emblematic of the successful return of public-private collaboration to Houston is the work of the Friends of Hermann Park (renamed the Hermann Park Conservancy in 2004), formed in 1992. The Friends commissioned a master plan from Hanna/Olin, Ltd. in 1993 (adopted in 1995), which has since successfully guided the renovation and revitalization of the park. Subsequent work by SWA Group, dubbed the “Heart of the Park” project, has realized the original vision for the park’s entry and reflecting pool. The project won an Award of Excellence in the design category from the American Society of Landscape Architects in 2005 and was a catalyst for re-focusing much attention on Houston’s parks. Another notable and more recent transformative project is the Discovery Green, a twelve-acre park completed in 2008 by Hargreaves Associates and designed to spur revitalization in the downtown district. Accommodating multiple programming needs, the park includes an oak allée, a promenade, open lawns, water features, and a pavilion. At a larger scale and providing for the conservation of natural ecosystems, ravines, and wildlife habitat is a recent master plan for Memorial Park. Nelson Byrd Woltz Landscape Architects was commissioned in 2013 to develop the plan to guide the park’s revitalization, responding in part to damage from Houston’s multi-year drought. Also impacted by the drought, the 155-acre Houston Arboretum and Nature Center that anchors Memorial Park is undergoing change. The master plan, developed by Design Workshop and Reed Hilderbrand, will diversify programming and address ecological habitat rejuvenation. Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates’ master plan for the Menil Collection Campus and the Freelon Group’s revitalization of the nearby ten-acre Emancipation Park (significant for its role in the Civil Rights movement) are other examples of the myriad and exciting ways in which landscape architecture is embracing Houston’s inherent natural and cultural values while contributing to its diverse constituencies and evolving identity.