Nashville's Landscape Legacy

Nashville is situated within the Central Basin of Middle Tennessee, framed by the Highland Rim, a curving wall of ridges that opens to the south. The Cumberland River snakes through the basin, which is underlain by a shelf of limestone, a ubiquitous building material in the region and a remnant of when it was an inland seabed. In a time before settlers arrived, Native Americans traversed the area, stalking wild game attracted to the salt lick that lay just east and north of the present Tennessee State Capitol.

The earliest European arrivals in the area were French trappers and traders, among them Charles Charleville, who opened a trading post in 1714. Between 1779 and 1780, early pioneers, led by James Robertson and John Donelson, entered the basin from North Carolina. They built Fort Nashborough, a two-acre, enclosed settlement along the banks of the Cumberland River, which was occupied until 1792. Farms and plantations were also established outside the fort, including Glen Leven, a 640-acre estate awarded to Thomas Thompson through a Revolutionary War grant, and Clover Bottom, claimed by Donelson himself.

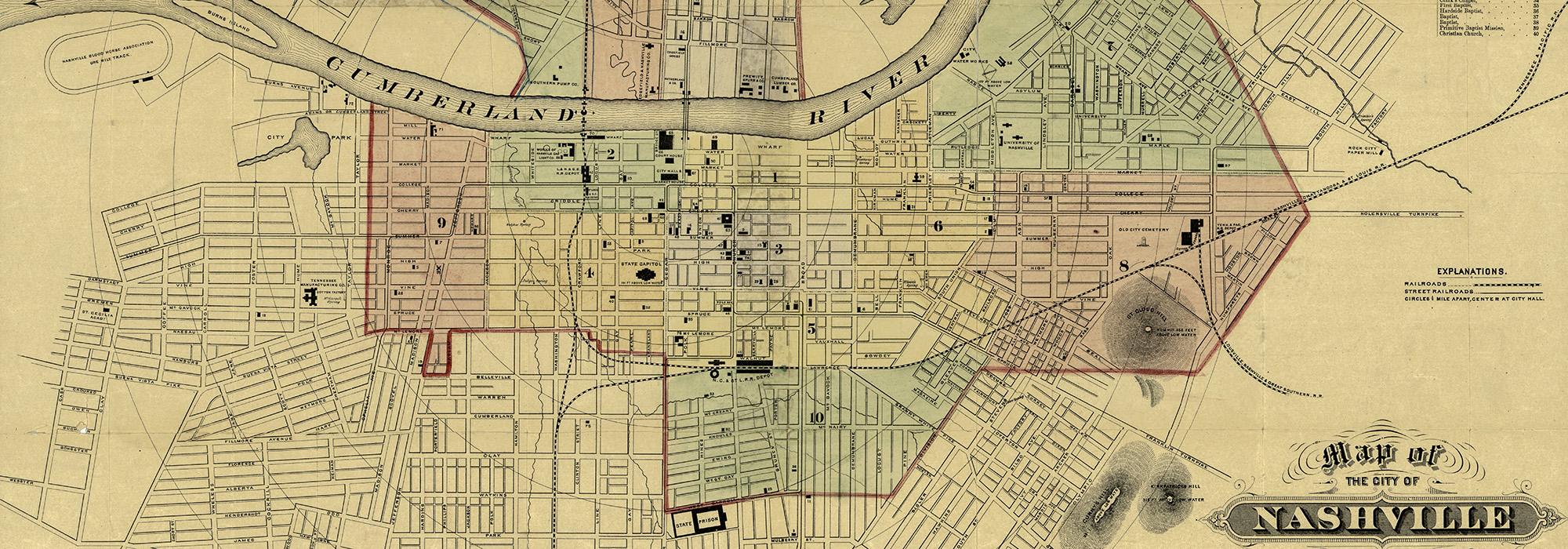

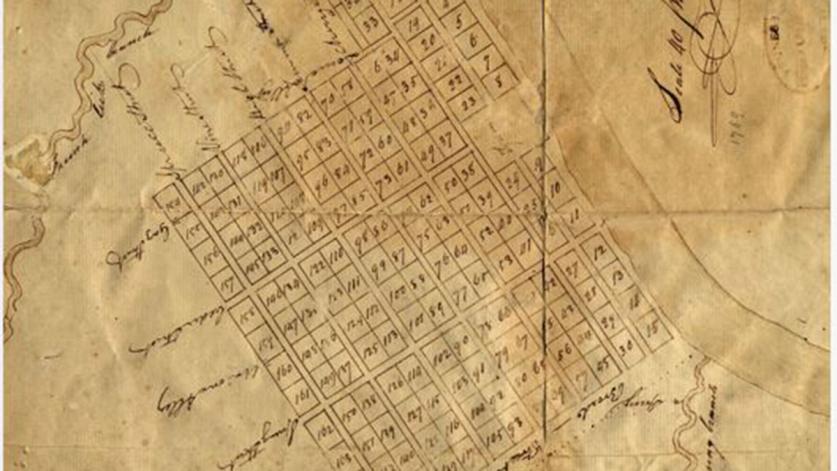

In 1784 surveyor Thomas Molloy created a plan for Nashville, consisting of a rectangular grid of 165 one-acre lots. The grid was composed of eight parallel north-south streets placed perpendicular to the town’s three thoroughfares, Broad, Cedar, and Spring Streets (since renamed Broadway, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard, and Church Street, respectively). The streets were oriented around a public square, which Molloy placed at the eastern edge of the grid on a bluff overlooking the river. Today, Nashville’s five-acre Public Square Park, located on the site of the original square, continues to serve as a central, civic space for Nashvillians.

Antebellum Nashville

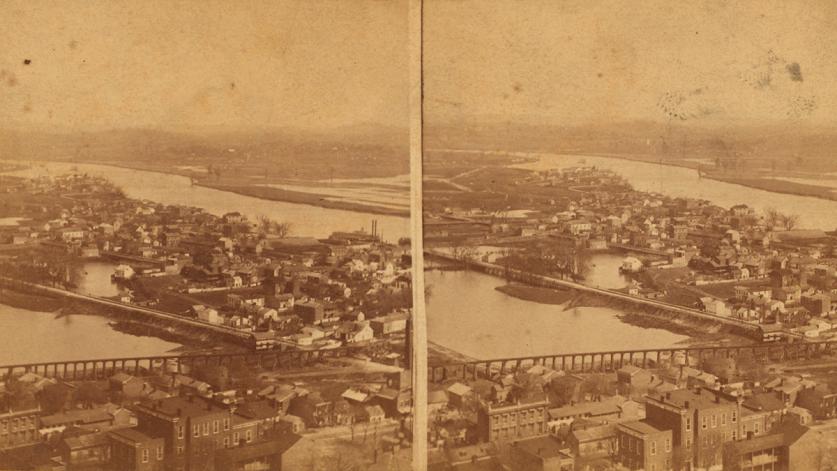

In 1806, ten years after Tennessee had attained statehood, Nashville was granted a city charter. The economy was primarily agrarian, dependent on the trade of commercial crops produced by the region’s farms and plantations, including Andrew Jackson’s Hermitage and Andrew Jackson Donelson’s Tulip Grove Mansion, two such estates whose houses and grounds have now been preserved as historic sites. Also important to the city’s success was the port of Nashville, located at the river end of Broad Street, now Lower Broadway. Bounded by First and Fifth Avenues, this segment of the street initially served as the city’s main entryway and connected the busy docks along the river to the city market on the Public Square via Market Street (now Second Avenue.)

The locomotive was first introduced to Nashville in 1853, and within a decade, railroad tracks traversed the region’s undeveloped ravines and bottomlands. Five rail lines were laid along a prominent natural depression on the western edge of town in 1861, and by the end of the century, the site known as the “Gulch” was transformed into a massive railyard that consisted of some three dozen tracks. New-found commercial success in the first half of the nineteenth century was accompanied by rapid population growth and the increased need for burial space. The earliest public burial ground, Nashville City Cemetery, had been established in 1822 from the plantation estate of Richard Cross, southwest of the city. The cemetery expanded in subsequent decades, while other burial grounds were founded outside the city center, including the Temple Cemetery (1854), Mount Olivet Cemetery (1855), and Calvary Cemetery (1868).

In part due to the city’s economic success, the Tennessee General Assembly selected Nashville as the permanent seat of the state capital in 1843. Located atop Cedar Knob, downtown Nashville’s highest point, the Tennessee State Capitol was built between 1845 and 1859. The structure was designed in the Greek Revival style, perpetuating the theme of Nashville as the ‘Athens of the South.’ Despite these economic and civic advancements, the city remained tethered to an agrarian economy that did not encourage urban growth. But war would prove to be the catalyst for change.

The Civil War and Reconstruction

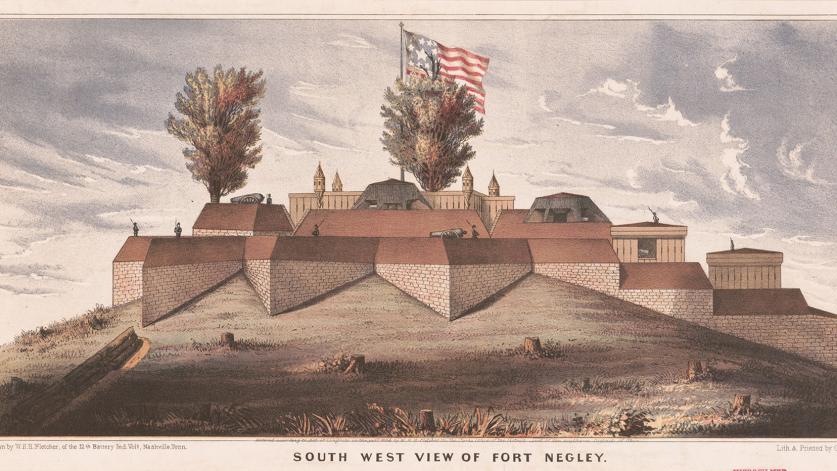

Tennessee formally seceded from the Union in June 1861, the last state to do so. Nashville fell to Union forces in 1862 and remained under federal occupation for the duration of the war. The city was secured by a series of forts to the south and west of the city. Fort Negley and Fort Casino (site of today’s Reservoir Park) were situated upon Saint Cloud Hill and Casino Hill, both selected for their rocky terrain and steep inclines. In December 1864, Confederate forces stationed themselves at the Travellers Rest plantation, a 2,300-acre cotton and tobacco estate six miles south of Fort Negley. The resulting Battle of Nashville, on December 15th and 16th , ended with one of the largest Union victories of the war.

Following the conflict, the city utilized the infrastructure left by the federal forces, including an expanded railway system and a new shipyard, to become a trade node between the Midwest and the Gulf. Manufacturing sites became prevalent downtown and along the waterfront. One such site was Rolling Hill Mill, adjacent to today’s Riverfront Park, which hosted a series of roller mills that processed grain and lumber prior to its conversion into a hospital complex in 1890. Almost simultaneously, the central business district expanded from the Public Square along the streets to the south and west, including Fifth Avenue, Market Street, and Printer’s Alley, transforming former residential areas and warehouse districts into major commercial thoroughfares populated by large neoclassical and Italianate store fronts. Similarly, the small commercial venues that occupied Upper Broadway before the war were replaced with large-scale religious, civic, and commercial institutions, including the Customs House and Christ Church Cathedral.

As the city prospered economically, Northern funds for educational institutions supported the establishment of multiple university and college campuses. These institutional campuses were developed away from Nashville’s crowded urban center on large tracts of land that could accommodate future expansion. Chartered in 1875, Vanderbilt University was laid out on a 75-acre parcel two miles south of downtown Nashville. It was later joined by the neighboring Peabody Normal College, a liberal arts school derived from the University of Nashville. Also in the 1870s, Fisk University, an African American normal college, relocated from its campus near today’s Upper Broadway, to a 25-acre former military base, north of Nashville.

Parcels of land outside the city were also adapted for recreational uses. West End Park, for example, served as the state fairgrounds and a race track before being chosen as the location of the 1897 Tennessee Centennial and International Exposition. Inspired by the World’s Columbian Exposition, held in 1893, the grounds were designed to include formal gardens, neoclassical buildings, and a man-made lake. Following the exposition’s closure, the site became Centennial Park. In 1892 a 434-acre parcel of land called ‘The Woodlands’ was sold to the Edgefield Land Company for development of suburbs east of the Cumberland River, of which a small parcel was developed into an amusement park called Shelby Park.

Late-Nineteenth and Twentieth-Century Urban Development

As trolley cars were introduced in the late nineteenth century, territory opened beyond the city, allowing the middle class to settle on undeveloped land between the town and country. In 1906 much of the 2,600-acre Belle Meade Plantation, located southwest of Nashville along the highland rim, was sold to the Bransford Realty Company and the Belle Meade Company. The property was subsequently subdivided for the creation of affluent residential communities, including today’s Belle Meade Golf Links Historic District, which featured spacious housing lots set along paved streets and interspersed with small community parks. Forming the spine of the subdivision was the six-mile Belle Meade Boulevard, a two-lane roadway that provided commuters access to the city. The residential community still maintains its exclusivity today.

A seminal year for Nashville’s cultural landscapes was 1901, when the Parks Board was founded and a plan was established for a citywide system of parks. Funding came via a deal that gave the Nashville Railway and Light Company a franchise in exchange for Centennial Park, as well as a share of the company’s gross earnings from streetcar fares. Through this arrangement, Nashville gained its first large, public park and a revenue stream to support future projects. In 1909 the Parks Board oversaw the purchase and expansion of Shelby Park, previously owned by the Edgefield Land Company, and in 1927 the Belle Meade Estate donated 868 acres of undeveloped land that would become the seed for the city’s Warner Parks, now occupying more than 3,000 acres.

It was also during this time that the city began building on the reputation for music that was begun by the Jubilee Singers of Fisk University some fifty years earlier. The famous Grand Ole Opry originated as the WSM Barn Dance stage show and was first broadcast in 1925 from Nashville’s WSM-AM studio. To expand its reach, the studio erected a new transmission tower in 1932. The WSM-AM tower’s ability to broadcast across 40 states helped establish Nashville as the “Country Music Capital.” The success of WSM-AM and other radio stations around Nashville ensured the city’s predominance in the genre and bolstered the formation of other significant cultural institutions, including Music Row, a former 200-acre streetcar suburb that became populated with recording studios after the district was zoned for commercial use following World War II.

The Late Twentieth Century and Beyond

Beginning in the 1970s, downtown Nashville witnessed a general decline as its manufacturing-based economy floundered in the post-industrial era. But in 1991 a revitalization effort was initiated that transformed the area's urban landscape. Lower Broadway, once a prominent commercial corridor, had declined with the closure of the famed Ryman Auditorium in 1974. As part of this revitalization effort, the auditorium was reopened, and the street segment was converted into a popular tourist destination. New municipal landscapes were also created, the most prominent being the nineteen-acre Bicentennial Capitol Mall State Park, placed directly north of the state capitol building in 1996. Large land acquisitions were also made for the development of parks and greenways, including the 1,500-acre Beaman Park and the Shelby Bottoms Natural Center and Greenway, which opened in 1997 and was later expanded in 2011 to its current size of 960 acres.

Another milestone was the 2006 Nashville Riverfront Redevelopment Master Plan, which brought new parks and recreational areas to both sides of the Cumberland River. On the east bank, the grounds of the former Nashville Bridge Company’s headquarters became Cumberland Park and Riverfront Landing, while directly opposite, on the western bluffs, Riverfront Park, with its Ascend Amphitheater, was developed on the site of the former Nashville Thermal Transfer Plant. In addition to these new waterfront developments, long-abandoned industrial areas, including the Gulch, were revitalized, and former brownfields sites, such as Rolling Mill Hill, became attractive, mixed-use neighborhoods. Symbolic of this era of transition, the parking lot that had replaced Nashville’s original Public Square during the 1970s was removed in 2007, and the square’s status as an important civic space was restored. Molloy’s original four-acre tract once again became the point of vantage for the city’s history in three dimensions, as it has been formed and re-formed for almost 250 years.