About New Orleans

Colonial Beginnings

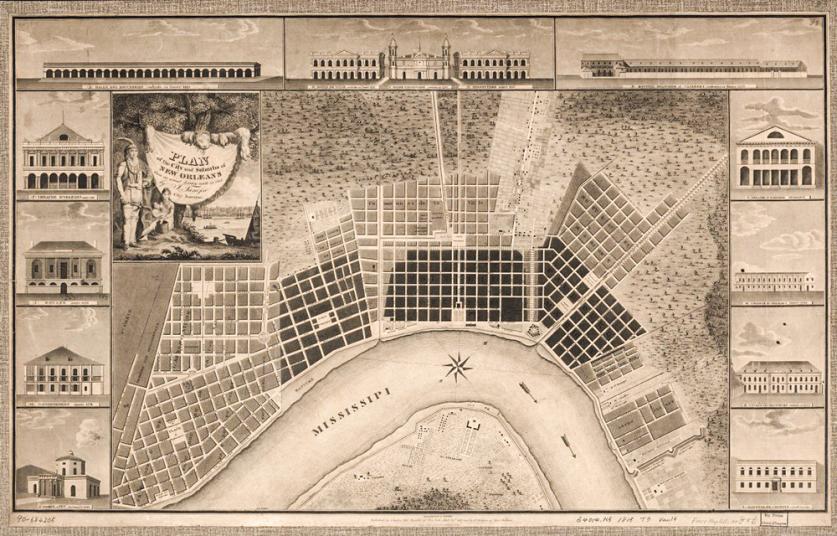

Founded in 1718 by Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville, the French settlement of Nouvelle-Orléans was established on a portion of relatively high ground at a sharp bend in the Mississippi River. The location chosen by de Bienville had the added advantage of being situated next to a portage long used by the native peoples who moved goods and supplies between the river and nearby Lake Pontchartrain to the north via Bayou St. John. Now a recreational corridor serving joggers and cyclists from multiple city neighborhoods, the bayou was once a primary transportation and trade route that traversed the region’s dense cypress swamps.

The original settlement around which the colony developed was the Vieux Carré (known today as the French Quarter), laid out as a rectilinear grid of streets and residential blocks. Within the Vieux Carré, a central public square facing the river was reserved for military drills, parades, and ceremonial gatherings. At first called the Place d’Armes (but re-named Jackson Square in 1851), this open space eventually became formalized with curvilinear walkways, statuary, and plantings placed atop a grassy lawn.

From its earliest beginnings as the colonial seat of government in 1720, New Orleans had been home to immigrants from Europe, Africa, and the Caribbean, many of whom were army deserters, vagabonds, and social outcasts. In 1763, the lands of the French colony passed to Spain. Under Spanish rule, the already culturally eclectic New Orleans, with a population of about 3,200 residents, saw an influx of immigrants from Spain and its colonies. Plantations producing indigo were at their height during this period—some 50, in all, were active—powered by African slave labor.

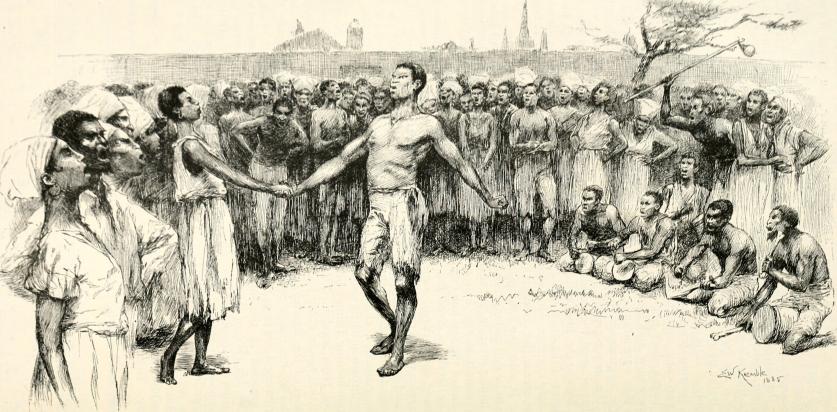

Just outside and to the north of the French Quarter, an open space of about three acres had come into regular use by the mid-eighteenth century, but for altogether unofficial purposes. Congo Square, as it would come to be known, was, at first, the informal site where traveling shows and performers could attract a crowd; but by the early years of the nineteenth century, the square would be designated as a weekly gathering place where, on Sundays, African and Native Americans were legally permitted to sing, dance, and play music.

The Nineteenth Century

With the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, Americans came to New Orleans in droves and began to invest heavily in the town, where swampland and woodlands still remained in close proximity to the original urban settlement. Expansion followed apace. To the north of Congo Square, in what was characterized as the ‘backswamp’ edge of town, free Africans and Creoles sought to build on the cheaper land of what would come to be known as Tremé, the neighborhood that is perhaps most associated with New Orleans’ rich musical heritage. Farther north, houses were constructed on large, newly established agricultural lots along Bayou St. John. The area was attractive enough to lure former New Orleans Mayor James Pitot from his townhouse on Royal Street in the Vieux Carré to live there in 1810.

Established in 1805 on land formerly belonging to the planation of Bernard Xaier Philippe de Marigny de Mandeville, the first suburb to develop downriver (east) from the Vieux Carré was Faubourg Marigny, a working-class enclave of Creole and Classical Revival cottages and shotgun-style houses with an open space near its center that would become known as Washington Square.

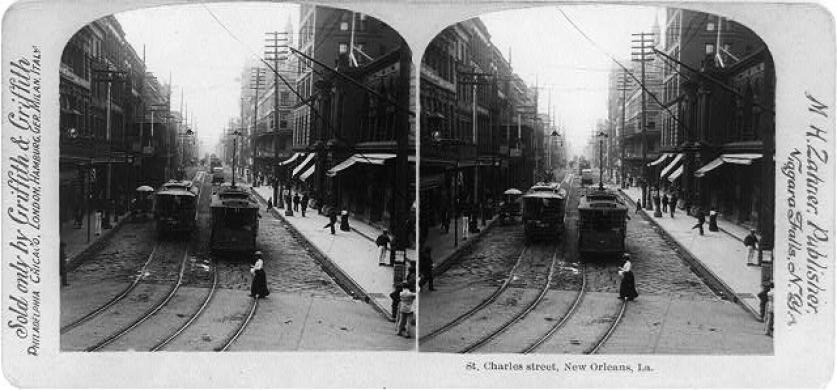

It was, however, Faubourg St. Mary, occupying land to the west of Canal Street, just upriver from the Vieux Carré, that became widely known as the American sector. An open space that would eventually be called Lafayette Square (after General Lafayette visited New Orleans in 1825) served as a counterpoint to the Place D’Armes in the French Quarter downriver, becoming a nexus of banking, commercial, and legal activities. Several other faubourgs (literally “false towns”) were established upriver, and those who purchased lots in the newly platted suburbs were responsible for planting trees along roads, canals, and drainage channels as they were constructed. UnlikeTremé and the Vieux Carré, these newly established enclaves upriver featured houses with side plots and ample setbacks from the street. Connecting these new neighborhoods to the center of New Orleans was the St. Charles Streetcar Line. Established in 1835, the line traced what was formerly the route of the New Orleans and Carrollton Rail Road. The Town of Carrollton, then the terminus of the streetcar line, was annexed by New Orleans in 1874. Still other rail lines connected New Orleans residents to several resorts along the southern shores of Lake Pontchartrain, including Milneburg, Spanish Fort, and other West End communities.

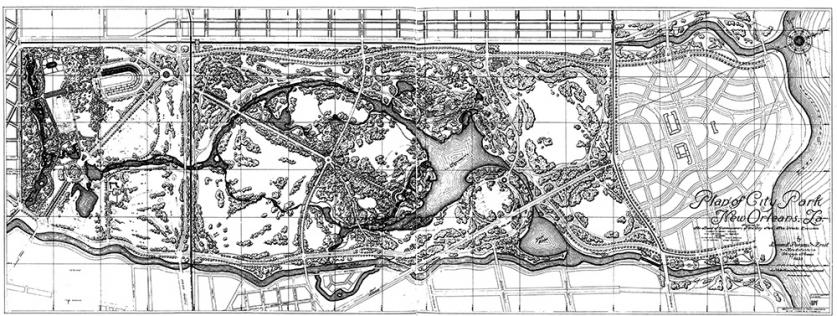

Before the close of the nineteenth century, New Orleans would see the advent of two large public parks: Originally part of the Allard Plantation, City Park (also known as Lower City Park) began to be developed in 1891 and would take shape in the early twentieth century to become a beacon of the City Beautiful movement. And Audubon Park, originally home to the1884 World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition, would later be shaped by the Olmsted Brothers firm, which would continue to work on the park into the 1940s.

From the Twentieth Century to Post-Katrina

By 1900, New Orleans’ population approached some 290,000 residents. After a flurry of building activity in the city’s two large-scale parks at the beginning of the new century, the nation and the city slumped in the midst of the Great Depression. It was during this period that the Works Progress Administration (WPA) carried out several projects throughout New Orleans. At City Park, the WPA built roads, bridges, and shelters; and at Audubon Park, work on the Audubon Park Zoo commenced. The WPA was also involved in renovations to the famous French Market, with its origins dating back to the colonial period.

An unfortunate turn of events came in the 1960s, when, in an effort to make the city more automobile-friendly, the “neutral ground” that was once home to Tremé’s Mardi Gras traditions was destroyed to make way for an elevated highway connecting suburban New Orleans to its downtown. But in the 1970s, the 31-acre Louis Armstrong Park was designed in Tremé to celebrate the neighborhood’s musical history, and the adjacent Congo Square was simultaneously renovated. Around this same time, the planning of open space first extended to the redevelopment of New Orleans’ riverfront, beginning with the Moon Walk opposite Jackson Square. Work continued along the riverfront in the 1980s with the advent of Woldenberg Park, stretching along the bend of the river at the base of Canal Street on the site of former industrial buildings and wharves. This trend has continued in more recent times with the design of Crescent Park (2008), which hugs the river in the Marigny and Bywater neighborhoods and incorporates two re-purposed wharves connected by a wide promenade.

Crescent Park also represents one of the city’s responses to the devastation brought by Hurricane Katrina—the “most expensive storm on record”—in 2005, as does the Lafitte Greenway, a recently conceived 2.6-mile linear park that follows the path of the former Carondelet Canal and interprets the various layers of the city’s history. Just as Katrina’s toll on the city’s residents was immense, so, too, was its awful effect on the city’s many cultural landscapes. Completely inundated by floodwaters, much of the city’s parkland lay neglected for several years following the hurricane, with some 2,000 trees lost in City Park alone. In many ways, the efforts to resurrect New Orleans’ cultural landscapes reflect the slow but steady recovery of the city as a whole, and the resilience of a population that is determined to re-build and to remember.