The Landscape Legacy of Rhinebeck & the Mid-Hudson Valley

The Hudson River forms the backbone of the Hudson Valley, which extends from Westchester County north of Manhattan to Albany’s Capital District, approximately 150 miles upstream. The region is generally divided into three sections: the upper, middle, and lower valley. While this guide highlights the Mid-Hudson Valley, The Cultural Landscape Foundation hopes that it will serve as a foundation for others to follow, the first in a series to make visible and instill value in the Hudson River Valley’s unique and unrivaled cultural landscape legacy.

From Glaciation to Revolution

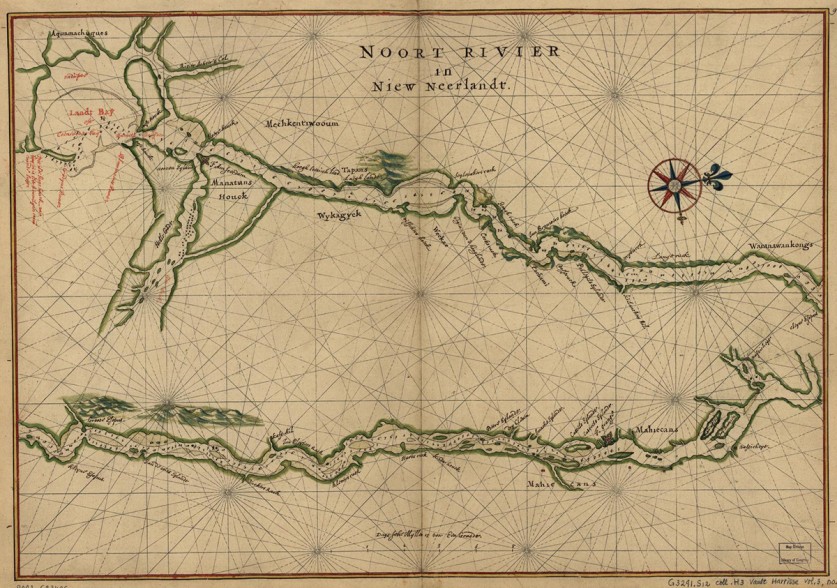

When Henry Hudson was engaged by the Dutch to find a faster route to the Orient in 1609, the English explorer instead stumbled upon the tidal river and valley that now bears his name. Physically shaped during and after the most recent glaciation event that ended approximately 10,000 years ago, the region impressed Hudson’s first mate, who wrote of the abundance of natural resources and land ideal for cultivation. Hardly a tabula rasa, the landscape was shaped over centuries by members of the Algonquin federation, who employed controlled burning techniques to create agricultural fields and established trails that were ultimately utilized and developed by non-native settlers. The first of these settlers to claim the land were the Dutch, who called the region New Netherland.

By 1664 Dutch rule had come to an end (except for a brief period from 1672 to 1674) and the Hudson Valley passed to the British, who named the colony the Province of New York.

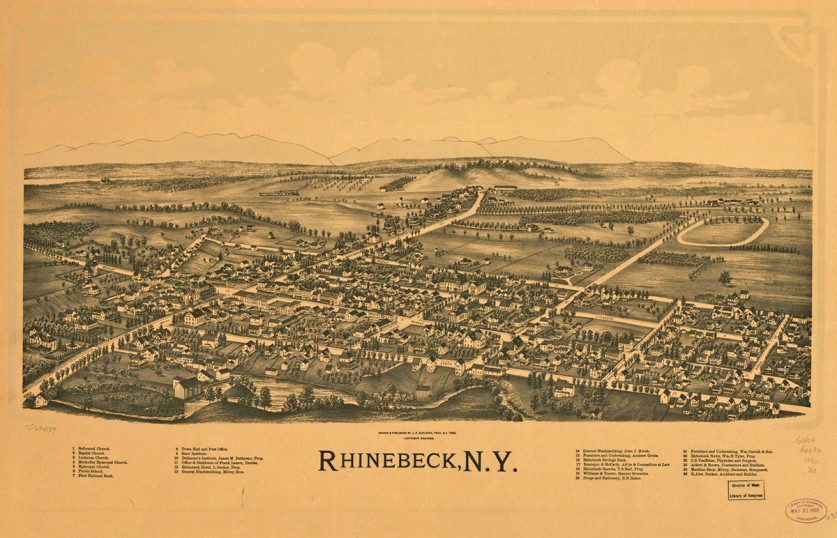

In 1683 the British established twelve counties, including Dutchess County, the geographic focus of this guide. Situated on the eastern shore of the river, the county was named after Mary of Modena, Duchess of York, and originally included present-day Putnam County and portions of Columbia County. From 1685 to 1706 the county was divided into fourteen land patents, conveyed to individuals and groups. Early European settlements were established along the river at present-day Beacon and Poughkeepsie and further inland at Fishkill and Rhinebeck. Under English rule men could acquire a grant (or patent), which they could then lease to tenants. This manorial system gave a relatively small number of landlords (or manor lords) control over their tenants, much like a feudal system. Agriculture flourished, particularly grain, and the region emerged as a colonial breadbasket. As agricultural production increased, New York became increasingly dependent on the labor of enslaved Africans.

The Hudson Valley, valued as a strategic location, agricultural hub, and trade route, was vehemently contested during the Revolutionary War, leading George Washington to refer to the region as the “key to victory.” Many enslaved Africans fought during the war, often sent to battle as substitutes for their owners. While the New York Manumission Society was founded after the war in 1785, slavery was still prevalent. In 1790 the first federal census counted 2,200 people of color living in Dutchess County, 80 percent of whom were enslaved. Among the slaveowners were members of the New York elite who inherited or purchased property on the eastern shore of the Hudson River, displacing yeoman farmers who relocated farther east. While slavery was generally accepted in the late eighteenth century, a community of free African Americans and emancipated individuals developed in present-day Hyde Park (Hackett Hill Park). Referred to as the New Guinea Community, the settlement provided refuge throughout the early- to mid-nineteenth century, eventually disbanding following the Civil War.

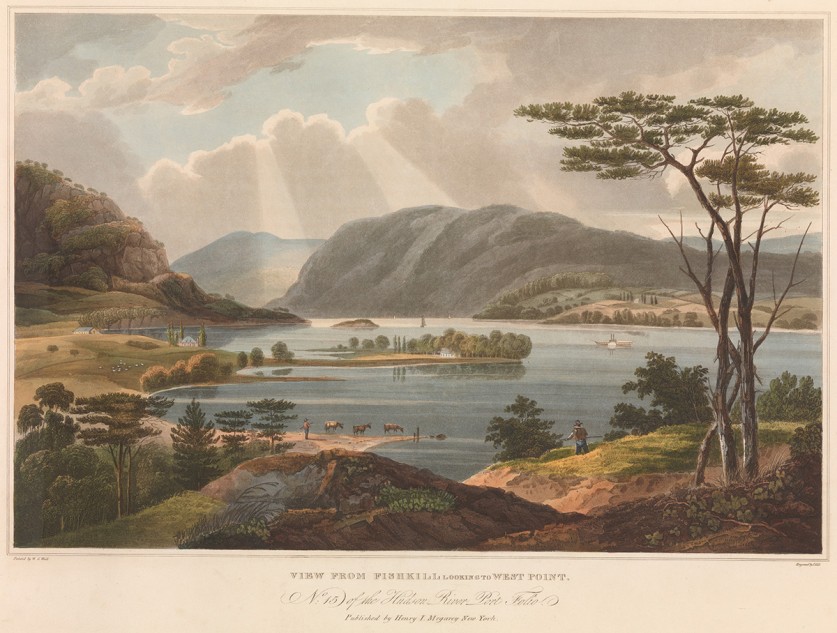

Landscape as Art

Just as the valley helped determine the outcome of the War for Independence, it influenced national taste throughout the subsequent century. Artists and writers came, drawing inspiration from its cultural landscape and its history. Thomas Cole championed the river and its setting, establishing the Hudson River School artistic movement. He and others, including students Fredric Edwin Church and Asher Durand, painted vivid and dramatic scenes inspired by or depicting the region. Writers such as Washington Irving and James Fenimore Cooper drew from local history and folklore. The many artists and writers who depicted the region helped shape public taste and attitudes toward scenic resources and the natural world, making the Hudson Valley a must-visit destination and place to live.

American aesthetics were shaped not only by the region’s novelists, poets, and painters, but also by landscape gardeners and horticulturists.

In 1828, four years after he emigrated to the United States from Belgium, André Parmentier introduced the European Picturesque style to an American audience with his design for the Hyde Park estate of professor, physician, and botanist Dr. David Hosack. Here, Parmentier established walks and drives following the site’s topography and strategically sited vantage points to afford expansive, borrowed views. While Parmentier was among the first to work in a Picturesque style, he was not alone. Hudson Valley native Andrew Jackson Downing inspired and influenced national taste through his practice as well as through his writing, editing of The Horticulturist magazine (1846-1952) and publishing four books in nine years, including Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1841) and The Architecture of Country Houses (1850). In 1850 he traveled to England and returned with architect Calvert Vaux. The pair collaborated on projects throughout the region, including Matthew Vassar’s ornamental farm, Springside, in Poughkeepsie (Vaux went on to fame when he collaborated with Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., on the 1858 Central Park design competition). Vassar also helped select a parcel of land nearby to serve as a rural cemetery. Designed by Howard Daniels and opened in 1853, the Poughkeepsie Rural Cemetery was one of many Picturesque cemeteries that developed throughout the nation following the opening of Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1831, offering a park-like setting for reflection and repose.

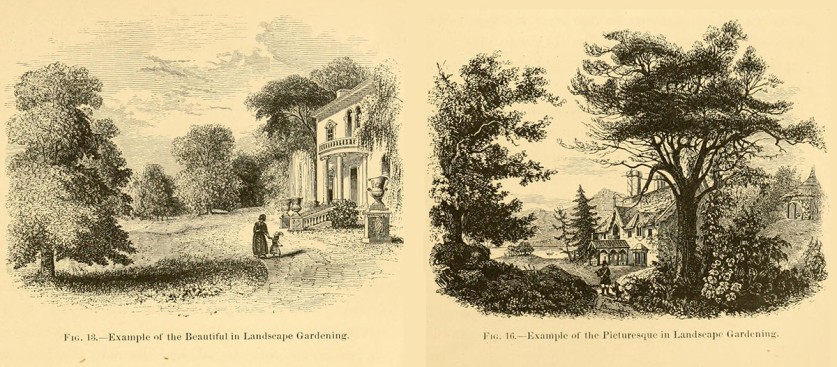

Downing’s writings and built landscapes established the Hudson Valley as the pastoral ideal, serving as a model for readers’ own villa residences and home grounds. Downing was the definitive tastemaker of his time, guiding the culture away from classical architecture and geometric gardens to less formal designs that he described as “Beautiful” and “Picturesque” in character.

Downing’s intellectual and aesthetic ideals influenced many of his peers. His friend Henry Winthrop Sargent, for instance, practiced landscape gardening and horticulture at his Woodenthe estate, located in present-day Beacon, designed the grounds of St. Luke’s (now St. Andrew and St. Luke Episcopal Church), and penned a supplement to the 1859 edition of Downing’s Treatise. The painter and inventor Samuel F.B. Morse developed his Poughkeepsie estate, Locust Grove, according to Picturesque principles, selectively establishing pastures and wooded lots to create a painterly scene visible from his Italianate villa perched atop a riverside bluff. Further north, Hans Jacob Ehlers improved the grounds of Rokeby in Barrytown and established an arboretum at nearby Montgomery Place in 1849. Ehlers purportedly designed the initial layout of the Ferncilff estate in Rhinebeck, which was later developed by his son Louis Augustus Ehlers.

After Downing perished in a steamboat fire in 1852 at the age of 36, Vaux continued to practice in the Hudson Valley, partnering with architect Frederick Clarke Withers. In 1855 Vaux designed the estate of Lydig Hoyt and his wife Blanche Livingston, located on a Hudson River promontory in the hamlet of Staatsburg (Hoyt House), and in 1869 was engaged by Frederic Edwin Church to collaborate on the design of the painter’s hilltop residence, Olana, approximately 25 miles north in Hudson. He showcased not just the cultivated fields and woodlands of the 250-acre estate, but also the river and mountains beyond. These borrowed views, or viewsheds, are a defining characteristic of the property and speak to the origins of American scenic conservation in the nineteenth century, inspiring twentieth-century notions of viewshed protection. Church advocated for scenographic views accessible to all, and expressed this democratic approach as early 1869 as part of a coalition advocating for the preservation of the scenery associated with Niagara Falls. Church’s influence is evident in the writing of his collaborator, Vaux, and the advocacy of Frederick Law Olmstead, Sr., the father of landscape architecture; the latter was a central figure in this advocacy campaign and the designer, along with Vaux, of the Niagara Reservation in 1887.

Changing Tides

The nineteenth century was marked by industrial and technological innovation that shaped the regional and national economy. In 1807 inventor Robert Fulton launched the world’s first practical steamboat off the West Side of Manhattan, revolutionizing trade and travel. The Erie Canal (1825) hastened the settlement of Midwestern territories and facilitated the movement of goods and people. The Croton Aqueduct (1842) provided Manhattan with potable drinking water, and by 1851 a railroad skirted the eastern shore of the Hudson River, connecting Manhattan with Albany’s Capital District.

The manorial system was abolished in 1846 and the advancements in trade and technology transformed the formerly agrarian economy. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, robber barons and their heirs acquired riverfront properties, and engaged prominent architectural firms to either redesign existing structures, including modest residences designed according to Downing’s principles, or create new palatial mansions atop riverfront bluffs and rises. These mansions afforded expansive panoramic views while simultaneously showcasing their wealth and status. By the late 1920s, over 30 grand mansions were sited near the river, primarily on its eastern shore, often accompanied by formal gardens. In 1915, for instance, a 34-year-old Franklin Delano Roosevelt and his mother engaged the architecture firm Hoppin & Koen to redesign their Springwood Estate (Home of Franklin D. Roosevelt National Historic Site) at Hyde Park. The firm transformed the residence, the birthplace and home of the future President, from an Italianate villa to a Georgian Revival mansion.

Completed in 1916, the redesigned Springwood residence, overlooking the river and grounds, shaped the course of Roosevelt’s life. It was his experiences roaming the estate, riding on horseback with his father, and ice-sailing on the frozen Hudson that instilled his love for nature and shaped his conservation ethic.

Roosevelt followed a tradition of gentleman farmers who enriched and stewarded their cultural landscapes. He developed a passion for agroforestry, eventually planting nearly half a million trees over a span of 35 years and forming a commitment to forestry and conservation that he maintained throughout his political career and personal life. As New York governor and then as President, Roosevelt, with his wife Eleanor as First Lady, championed forestry and publicly recognized their benefits. Shortly after becoming President of the United States in 1933 Roosevelt formed the Civilian Conservation Corp (CCC) to create jobs and lift the nation out of the depression. Known as “Roosevelt’s Tree Army,” the CCC employed more than 2.5 million young men for nearly ten years, establishing roads and trails, and reforesting large swaths of land. One CCC camp was located less than five miles upriver from Springwood, in what is now Mills-Norrie State Park.

Eleanor Roosevelt similarly found solace and inspiration from Dutchess County’s bucolic landscape. At Val Kill (Eleanor Roosevelt National Historic Site), established in the 1920s on land purchased by her husband in 1911, she developed as a political leader in her own right. She formed a joint business venture with her friends Marion Dickerman and Nancy Cook, employing local farmers and craftsmen. At the retreat, she routinely walked the forested roads and trails, which inspired her influential "My Day" newspaper column.

The Roosevelts also advocated for the democratization of Hudson Valley landscapes. In 1938, after the death of Frederick Vanderbilt, who had purchased from the Hosack family the neighboring Hyde Park estate originally laid out by Parmentier in 1895, Roosevelt expressed his long-held desire that the property “might be made into an arboretum for the public.” Roosevelt was instrumental in the acquisition of the property and its designation as a National Historic Site (Vanderbilt Mansion National Historic Site). Roosevelt similarly left his home to the federal government after his death in 1945.

Landscape Patronage Takes Hold

The Roosevelts' legacy of patronage took root in the Hudson Valley. Dutchess County alone is replete with examples of formerly private or industrial landscapes that were turned over to the public for their scenic and cultural enjoyment, including the Astor estate (now Ferncliff Forest Game Refuge and Forest Preserve), the Verplanck estate (now Stony Kill Farm Environmental Center, part of SUNY Farmingdale), and the Suckley estate (Wilderstein Historic Site, now a house museum).

In addition to these estate transformations for the public’s benefit, patronage in the Mid-Hudson Valley extended to the establishment of libraries, institutions of higher learning, and commemorative landscapes. Multiple colleges were established in Dutchess County during the nineteenth century including Vassar College, Poughkeepsie Collegiate School (College Hill Park), and Bard College, the campus of which was assembled through the acquisition of several estates, including Blithewood, Montgomery Place and Ward Manor. At Vassar College, the Dutchess County Outdoor Educational Laboratory was established in the 1920s by Botany Chair Edith Roberts. Roberts and Elsa Rehmann, a landscape architect and Vassar instructor, were among the first to promote the use of native plants in American gardens.

After the Civil War, monuments were erected throughout the region to commemorate the fallen. In Poughkeepsie a decorative fountain inscribed with the words, “To The Patriot Dead,” was sited in a formerly-blighted modest triangular green (Soldiers' Memorial Fountain and Park), suggesting the growing demand for commemorative landscapes. Following World War I, Oakleigh and Helen Thorne provided land for the creation of the Millbrook Tribute Garden as a living memorial to local veterans. In the Village of Rhinebeck, Legion Memorial Park was established in the 1950s to commemorate World War II veterans.

With the demolition of Pennsylvania Station in New York City in 1963, the urgency to preserve significant historic structures and places surged. Two years later, the Olana Preservation (later the Olana Partnership) was incorporated to preserve and protect Frederick Church’s 250-acre masterpiece, including its setting and the panoramic “borrowed” views that inspired Church.

Scenic Hudson acts as another guardian protecting Olana’s viewshed as well as other significant views throughout the region by acquiring conservation easements. The group formed in 1963 to oppose a power plant proposed by Consolidated Edison at Storm King Mountain that would deface the iconic “north gate” of the Hudson Highlands range. The 1965 Scenic Hudson decision issued by the Second Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals, affording citizens the legal right to advocate on behalf of the natural world, continues to serve as a cornerstone of environmental law. In 1993 the organization acquired a 123-acre orchard adjacent to Olana and has since protected 1,500 acres of Olana’s viewshed. To date, the organization has conserved more than 48,000 acres throughout the region and helped establish more than 40 public parks, including Poets' Walk Park (1996) and Long Dock Park (completed in 2019 by Reed Hilderbrand). Scenic Hudson similarly preserves and protects working farms, which have collectively shaped the region’s cultural lifeways for centuries.

The Region Returns to Its Roots

Historically an agrarian landscape and economy, the Mid-Hudson Valley continues to be a national leader in the production of food and the culinary arts. In 1972 the Culinary Institute of America (CIA) relocated from New Haven, Connecticut, to Hyde Park and has since emerged as one of the premier American culinary schools. The institution not only produces world-renowned chefs but has also fostered a farm-to-table movement, capitalizing on the region’s agricultural riches. Many graduates have remained in the valley, working in concert with producers. Established in 2004, Stone Barns Center for Food and Agriculture, and its partner restaurant Blue Hill at Stone Barns, have advanced ecological farming practices, bringing together farmers, chefs, diners, and educators.

The region that is home to Innisfree Garden, Manitoga, Opus 40, and other cultural landscapes created during the last half of the twentieth century, reminds us that not only do artists see the world in a different way, but that the tradition of exploring the relationship between art and landscape continues today at such institutions as Dia Beacon and the Storm King Art Center. In recent decades visual artists have flocked to Hudson Valley to live and practice, and to draw inspiration from the landscape, much like Thomas Cole and his students did throughout the nineteenth century.

Today, Rhinebeck and the Mid-Hudson Valley’s extraordinarily diverse cultural, natural, and scenic resources continue to attract residents and visitors alike. Since 2000, the Mid-Hudson Valley’s population has grown by nearly nine percent. Not surprising. As Franklin Roosevelt once declared, “All that is in me cries out to go back to my home on the Hudson River.”