San Francisco Bay Area's Landscape Legacy

Early Spanish Colonization

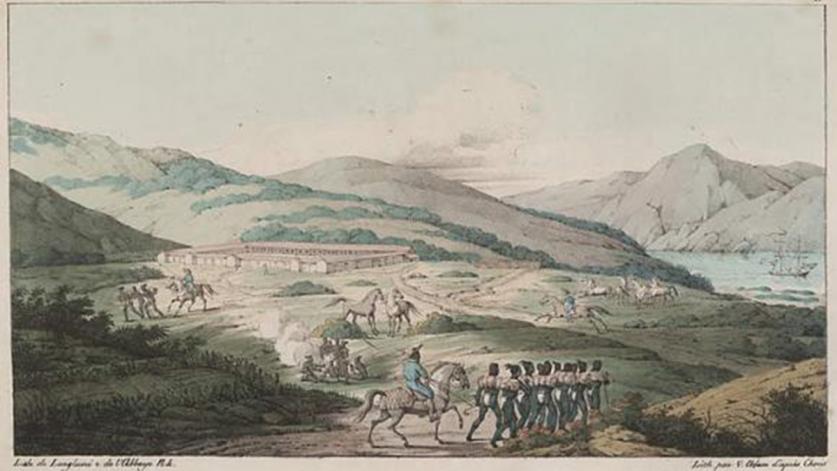

Before European settlement, the Bay Area was traversed by the Ohlone people, whose territory extended from today’s San Francisco Peninsula to Big Sur. The Ohlone transformed the land using slash-and-burn agriculture to harvest crops from fertile regions, including the Coyote Valley. In 1776 a Spanish expedition led by Juan Bautista de Anza established the Presidio of San Francisco, a military fort overlooking the Golden Gate Strait, and the Mission San Francisco de Asis. A small workers’ settlement named Yerba Buena was placed between the fort and mission, within today’s South of Market neighborhood. A harbor at Yerba Buena Cove, established for trade and naval vessels, has long since been in-filled and converted into Market Street. Before the end of the century, the Spanish government built two additional forts: Castillo de San Joaquin, near today’s Fort Point, and the Bateria de Yerba Buena, occupying the site of the current Fort Mason. To encourage settlement within Alta California, the Spanish crown awarded individual land grants, typically of 22,000 acres, called Rancheros, to the Presidio’s long-serving soldiers.

Yerba Buena

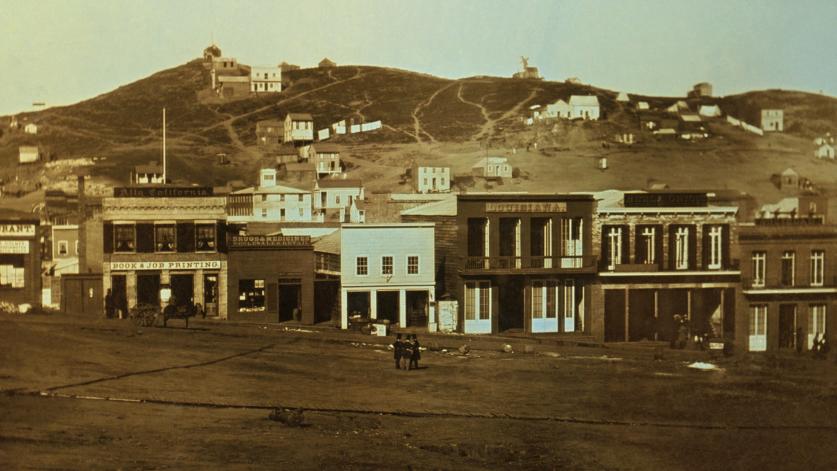

After Mexico won independence from Spain in 1821, the Yerba Buena settlement developed into a successful trading post. In 1839 the governor of Alta California, Juan Bautista Alvarado, commissioned Jean Jacques Vioget to survey the town. The resulting map established an initial street layout beginning at the shoreline, between the present-day neighborhoods of Chinatown and the Financial District. During the Mexican-American War, the town and harbor of Yerba Buena were seized by American forces who renamed the town’s central plaza Portsmouth Square. On January 30, 1847, Washington Bartlett, a lieutenant in the U.S. Army, issued a proclamation officially changing the name of Yerba Buena to San Francisco. That same year he commissioned one Jasper O’Farrell to survey the town yet again. O’Farrell’s map reformed Vioget’s oblique design with an orthogonal, rectangular grid that extended the town’s boundaries to the current Post, Mason, and Green Streets. Perhaps most significantly, he laid out the city’s main thoroughfare, Market Street, a 120-foot-wide diagonal boulevard that connected the town center to the outlying Mission region. His uniform plan of parallel streets and right-angled intersections established the pattern that would accommodate the town’s rapid expansion during its first population boom, which was soon to come.

San Francisco as an Instant City

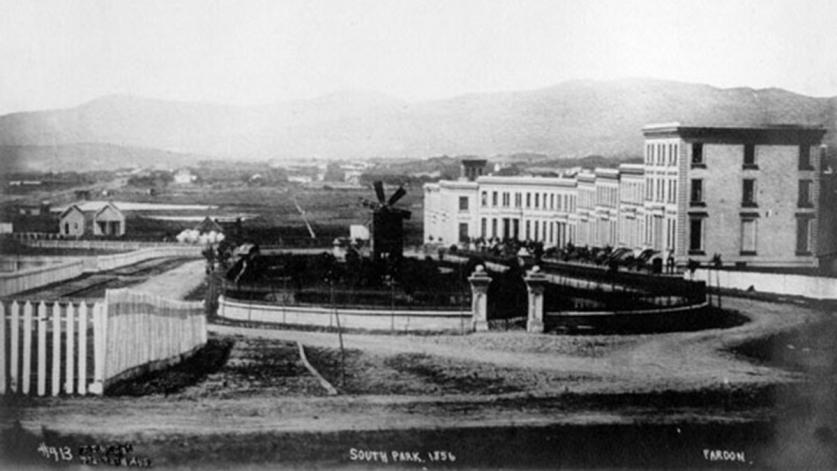

The California Gold Rush of 1848 marked the beginning of a significant transformation of the region. San Francisco’s population skyrocketed from approximately 5,000 residents in 1849 to more than 25,000 within a year. To accommodate the sudden growth, the city was extended eastward into the Bay via a series of landfills that now includes the neighborhoods of South of Market and Mission Bay. These areas and other downtown regions, including Jefferson Street, were settled by successive waves of immigrant communities, resulting in a process of cultural exchange that has never ceased. In 1856 the California State Legislature passed the Consolidation Act, which allowed rural land west of the city to be surveyed for development. Extending beyond Larkin Street to the current Divisadero Street, the 500-block tract, called the Western Addition, was platted by city surveyor William Eddy in the late 1850s, extending the rectangular grid first established by O’Farrell. With the introduction of the streetcar in the 1870s, the new addition was transformed into a residential enclave that is known today as the Fillmore District and is characterized by its Victorian architecture. The development of new residential enclaves also resulted in the creation of new public spaces, including Washington Square, now Marin Plaza, laid out by O’Farrell in 1849, and South Park, designed by architect George Goddard in 1852.

Outside the city, land speculators began developing properties formerly owned by Mexican citizens. On the Peralta family’s estate of Encinal, for example, speculators Horace Carpenter, Edson Adams, and Andrew Moon established a small settlement named Contra Costa. The settlement, renamed Oakland, was first incorporated as a town in 1852. In 1866 the College of California (founded in 1853 as the Contra Costa Academy), having outgrown its downtown setting, purchased 160 acres north of the city for a new campus. The college commissioned landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., to survey the land and design a campus plan. While largely unrealized, Olmsted’s plan established the campus’ east-west axis while preserving Strawberry Creek and the viewshed of the Golden Gate. Following the college’s merger with the Agriculture, Mining, and Mechanical Arts College, and its subsequent incorporation as the University of California in 1868, a new Picturesque campus design was completed by landscape architect William Hammond Hall. Renamed the University of California at Berkeley in 1953, the school would expand to cover more than 1,200 acres and would undergo a series of significant redesigns, including those by architect John Galen Howard in 1901 and landscape architect Thomas Church in 1962. The college also hired Olmsted to design what would be his first residential subdivision, the so-called Berkeley Property, divided by Piedmont Avenue, his first curvilinear parkway. The growing region attracted missionary Cyrus Mills who, having founded the first ladies seminary on the west coast, relocated his institution, renamed Mills College, to Oakland in 1871. Initially designed in the Picturesque style, the campus was redesigned by Bernard Maybeck and Walter Ratcliffe in the early twentieth century, resulting in its current Beaux-Arts layout.

The completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869 and the Bay Area’s resulting population boom spurred San Francisco’s civic leaders and philanthropists to advocate for open, public spaces to rival those of Paris or New York City. In 1870 some 1,017 acres west of the city were secured by the state legislature for the development of Golden Gate Park. This large Picturesque park was initially designed by William Hammond Hall, who replaced the land’s natural scrub with more than 155,000 trees. Corresponding closely with Olmsted, Sr., Hall transformed the eastern portion of Golden Gate Park into a formalized landscape complete with gardens and cultural attractions, including the Conservatory of Flowers, and one of the nation’s earliest playgrounds, Sharon Quarters. The Japanese Tea Garden and the Music Concourse were established as part of the California Midwinter International Exposition, hosted in the park in 1894. Still other recreational amenities were developed, including Pioneer Park, formed atop Telegraph Hill in 1876, and German-American Engineer Adolph Sutro’s Sutro Heights Park, now located in the Golden Gate National Recreational Area. Sutro also built outdoor baths along the western edge of Lands End, a popular coastal destination that was also integrated into the Golden Gate National Recreational Area during the late twentieth century. To access both sites, he personally funded a streetcar line along the recently developed Richmond District’s Clement Street, turning it into a major commercial corridor.

The 1906 San Francisco Earthquake and Twentieth-Century Urban Development

The rise of the City Beautiful movement at the turn of the century brought heightened attention to the correlation between public health and the urban environment. Impressed by the improvements made in Chicago, Illinois, and the District of Columbia, city leaders formed the Association for the Improvement and Adornment of San Francisco in 1904. Aspiring to transform San Francisco into the ‘Paris of the Pacific,’ the committee commissioned architect Daniel Burnham to create an urban plan for the city. Burnham, collaborating with his assistant Edward Bennett, proposed a new circulation network of thoroughfares and roundabouts that would connect the city’s civic center to a 30-mile-long outer boulevard along the waterfront. Located at the intersection of Market Street and Van Ness Avenue, the city center would be occupied by administrative and cultural institutions, while the surrounding hillsides were to be converted into a park system. Such improvements would, however, languish in the face of a natural disaster, the likes of which the city had never seen before.

On April 18, 1906, an earthquake devastated the Bay Area, causing significant damage from Marin County to the City of San Jose. Following the initial quake, fires erupted across San Francisco, razing 80 percent of the built environment. Left relatively untouched, the Western Addition was overwhelmed by both refugees and industries, while other areas, including Van Ness Avenue and the Mission District, became new centers of commercial development. In the wake of the disaster, the key elements of Burnham’s 1905 plan were set aside, but his more practical proposals for widened streets and diagonal thoroughfares were later realized. The city recovered quickly, even expanding to include new residential developments such as St. Francis Woods, designed by the Olmsted Brothers firm and John Galen Howard in 1913. Proud of the city’s rapid rebirth, civic leaders offered to host the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition. In anticipation of the event, the Civic Center Plaza, originally designed by John Galen Howard, Frederick W. Meyer, and John Reid, Jr., was placed near the intersection of Van Ness Avenue and Market Street. Reminiscent of Burnham’s plan, the design consisted of a Beaux-Arts plaza surrounded by a Classical-style city hall, public library, and exposition hall, with additional structures built in later decades. Over time, the landscape design continued to evolve throughout the mid-to-late twentieth century, with later Modernist contributions made by landscape architects Thomas Church, Douglas Baylis, and Lawrence Halprin, the latter adding the United Nations Plaza at the site’s eastern end at Market Street in 1975.

The 1920s was as period of prosperity for the San Francisco Bay Area. During this decade the population rose by twenty percent, leading to the development of new streetcar suburbs along the western edge of the peninsula. As the automobile became a permanent feature, the city constructed both the Great Highway, which borders the western peninsula along Ocean Beach, and the Bay Shore Freeway, connecting San Francisco to San Jose. Despite the hardships of the Great Depression of the 1930s, improvements continued with the assistance of the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration (WPA). Bookended by Fort Mason and Fisherman’s Wharf, a popular beach cove was converted by the WPA into Aquatic Park Pier, now part of the San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park. Among the WPA’s many projects in the region was the improvement of Sigmund Stern Grove, established in 1932, to include a stone amphitheater, subsequently transformed into stone terrace steps by Lawrence Halprin in 2005. The park was later adjoined by 50 acres, purchased by the city, for the formation of Pine Lake Park. At the hilltop Pioneer Park, which culminates in the 210-foot-tall Art Deco Coit Tower, the WPA planted cypress, pine, and tea trees and constructed rubble walls. In addition to park development, New Deal agencies assisted in building both the Golden Gate and the San Francisco-Oakland Bridges, connecting the peninsula to the surrounding Bay Area. In celebration of the bridges’ completion, the city hosted the Golden Gate International Exposition on Treasure Island, a one-square-mile, man-made island situated within the Golden Gate Strait. After the exposition closed in 1940, much of the grounds were razed to make way for an airport, which was then leased to the U.S. Navy at the outbreak of World War II.

The Late Twentieth Century and Beyond

During World War II, the San Francisco Bay Area was the main embarkation point and supply center for the Pacific Theater. The Presidio of San Francisco, and Fort Baker, established in 1901, were heavily fortified, while many recreational and commercial sites, including Aquatic Park and Treasure Island, were seized for military use. Meanwhile, the city’s historic Japanese enclaves in the Western Addition were emptied as a result of Executive Order 9066, which established war relocation centers across the country. To the south, San Jose became a center for defense manufacturing, attracting such technological powerhouses as IBM, which would come to define the region in the postwar era.

After the war, many military personnel settled within the Bay Area, giving rise to suburban developments west and south of San Francisco, including Visitacion Valley and Parkmerced. The Bay Area’s need for housing provided opportunities for emerging Modernist landscape architects, many of whom were graduates of the University of California at Berkeley, to experiment with progressive design. San Francisco-based landscape architect Thomas Church, a pioneer of the Modernist “California Style,” emphasized the unification of indoor and outdoor living space in his design of the Sunset Magazine Headquarters in Menlo Park, near Palo Alto, and his improvements to Stanford University, originally designed by Olmsted, Sr. in 1885. His designs influenced emerging landscape architects in the area, including Robert Royston, who, with the firms Eckbo, Royston & Williams, and Royston, Hanamoto & Mayes, completed work on Mitchell Park and Bowden Park, both in Palo Alto, and the Marin Art and Garden Center in Ross. In 1955 Lawrence Halprin, a protégé of Church, worked alongside architect William Wurster, of Wurster, Bernardi & Emmons, to develop Greenwood Common, a residential enclave in Berkeley. Halprin and Wurster partnered again in 1964 to transform the former industrial site of Ghirardelli Square into a shopping and dining center. In one of the nation’s earliest and most successful examples of historic preservation, Halprin retained and refitted the site’s original structures while introducing Modernist design features, including fountains, terraces, and historically referential lampposts. He also turned the complex’s signature sign 180 degrees to face the Bay. The project, with its innovative underground garage (conceived by Halprin), was underwritten by civic leader William Roth and was, in part, aimed at reversing the decline of San Francisco’s downtown, a by-product of postwar suburbanization.

As many White, middle-class residents left San Francisco for the surrounding suburbs between 1954 and 1974, longstanding commercial and industrial centers relocated to Santa Clara, San Jose, and elsewhere. The emptying of San Francisco’s downtown and the expansion of so-called blight within the Fillmore District and Mission Valley neighborhoods spurred calls for urban renewal. The San Francisco Redevelopment Agency began the renewal process by redeveloping Produce Market, an Italian neighborhood, which became the Golden Gateway, a mixed-used development designed by Sasaki, Walker and Associates in conjunction with Wurster, Bernardi & Emmons and DeMars and Reay. Public spaces within Golden Gateway included One Maritime Plaza and Sydney G. Walton Square, both by Sasaki, Walker and Associates, and the Embarcadero-Justin Herman Plaza, by Lawrence Halprin, Mario Ciampi and Associates, and John Bolles & Associates.

The agency also “improved” neighborhoods within the Western Addition that were, in fact, thriving African American and Latino communities. The so-called slum removal resulted in the relocation of some 4,000 residents from historic neighborhoods. At the same time, the implementation of the Bay Area Rapid Transit system (BART) connected Oakland and San Francisco with the outlying suburban communities of the Alameda, Contra Costa, and San Mateo Counties, encouraging further regional growth. The system’s realization resulted in such sites as the multi-tiered Modernist One Post Plaza, designed by Sasaki, Walker and Associates, which served as a shopping center that also offered a connection to the BART/Muni System one level below. The new transit network also coincided with the redevelopment of Market Street by the design firms of Lawrence Halprin & Associates, John Carl Warnecke & Associates, and Mario Ciampi and Associates. In addition to their municipal commissions, landscape architects contributed to the Modernist designs of corporate campuses and cultural institutions, including the Kaiser Center Roof Garden, designed by Osmundson & Staley landscape architects in 1960, and the terraced, rooftop gardens of the Oakland Museum of California, created by the Office of Dan Kiley, working with Geraldine Knight Scott, in 1969.

In 1989 the Loma Prieta earthquake resulted in significant damage, especially in San Francisco and Oakland. The subsequent dismantling of the heavily damaged Embarcadero Freeway opened up new land in the South of Market District. That same year, the centuries-old Presidio was decommissioned and transferred to the National Park Service as part of the Golden Gate Recreational Area. In 1999 Congress created the Presidio Trust to help co-manage the park by overseeing such projects as the development of the Letterman Digital Arts Campus by Lawrence Halprin in 2005, and the rehabilitation of Crissy Field by Hargreaves Associates. In recent years the Trust’s work has included the restoration of the Presidio’s natural bluffs and its historic forest, in addition to installing a series of scenic overlooks.

Between 1998 to 2008, Mission Bay, a former tidal basin and industrial site was converted into a mixed-use waterfront development, with work by landscape architecture firms Olin Partnership, MFLA Marta Fry Landscape Associates, EDAW, and Antonia Bava Landscape Architects. The neighborhood has become an epicenter of landscape architecture practice, including projects by PWP Landscape Architecture; AECOM; Andrea Cochran Landscape; Wallace Roberts & Todd; Royston, Hanamoto, Alley and Abey; and SWA Group. Nearby, a neglected industrial right-of-way became Daggett Park, designed by CMG Landscape Architecture in 2016. Originally developed in 1852, South Park, San Francisco’s oldest park, was redesigned by Fletcher Studio in 2017. Not far away, in the heart of downtown, the old Transbay Terminal was rebuilt in 2018 as the Salesforce Transit Center. The center is topped by Salesforce Park, a densely planted, linear rooftop park designed by PWP Landscape Architecture. With these and other projects, the Bay Area continues to evolve. And just as it was in the Beaux-Arts and Modernist eras, landscape architecture is a driving, innovative force behind that evolution.