St. Louis and the Missouri River Valley's Landscape Legacy

The bluffs, terraces, and fertile prairie lands that make up the area surrounding the confluence of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers have shaped the geographical and cultural history of the region for millennia. These waterways were a vital part of Mississippian civilization, which dominated the Midwestern and Southeastern part of the United States for centuries prior to European contact. Interconnected settlements, including the largest Mississippian city of Cahokia, home to 20,000 people at its peak in the thirteenth century and a mere ten miles from present day St. Louis, were recognizable across the valley from great distances due to their distinctive earthwork mounds. By the seventeenth century, the dozen tribes that made up the Illini Confederation populated the area, though as the United States began to grow, the commercial opportunities offered by the rivers began to attract increasing numbers of European traders. Explorer René-Robert Cavelier (known as La Salle) claimed the entire Mississippi River valley as a colony of France in 1682.

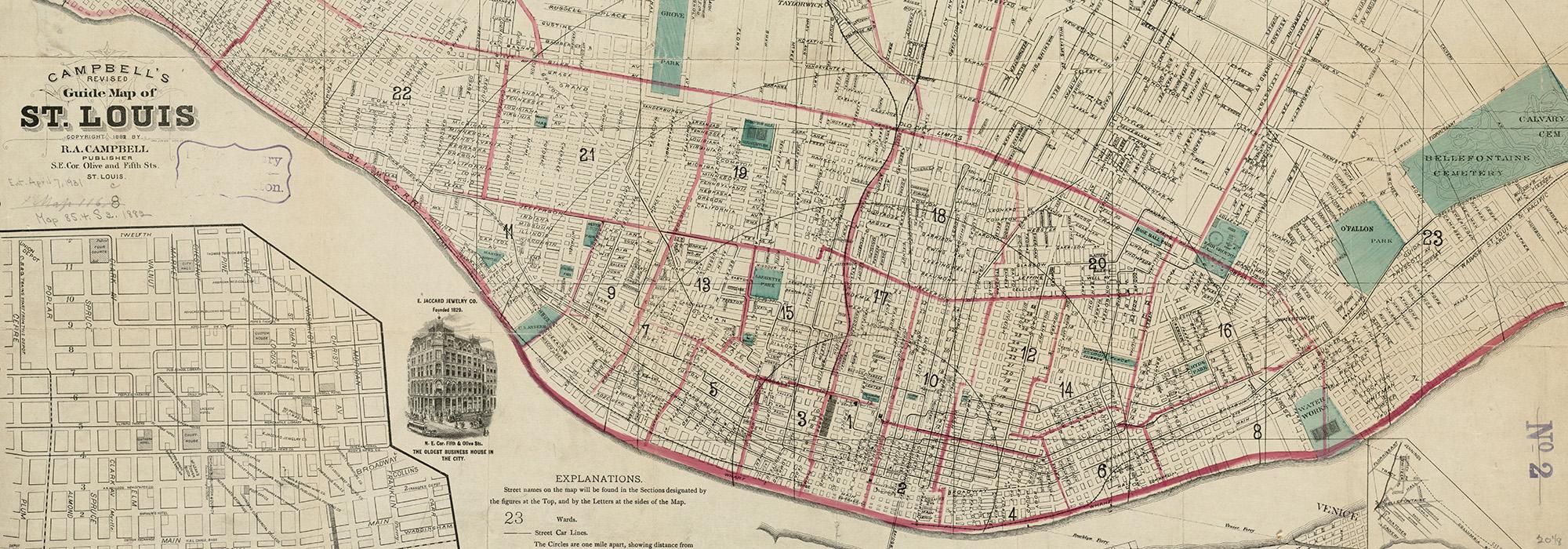

Eight decades later in 1763, merchant Pierre Laclède and his fourteen-year-old charge Auguste Chouteau set up a fur trading post just south of the confluence of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers, where a limestone bluff sloped gently west from the Mississippi River’s bank, covered by an expanse of rolling prairie irregularly dotted with old growth forests and traversed by rivers and creeks. Within a year, they had established the village of St. Louis, named in honor of Louis XV of France. The sophisticated city grid they devised set St. Louis apart from other Creole and colonial villages in the area, which were mostly vernacular arrangements of residential, civic, and agricultural spaces. The grid established by Laclède and Chouteau shared similarities with their native New Orleans, with a central marketplace near the river and city blocks each three hundred French feet square running parallel inland. Privately held lots were enclosed by wooden fences and stone walls, and commons both for livestock grazing and cultivation were established. A path between St. Louis and the Missouri River to the north was laid out in the late eighteenth century, referred to in the colonial custom as the King’s Road or King’s Highway.

The territory including St. Louis was transferred to Spanish occupation in 1770 under the Treaty of Fontainebleau, though French settlers continued to arrive, and a secret treaty arranged by Napoleon soon returned the colony to the French shortly thereafter. In 1803, the Louisiana Purchase ceded the territory including St. Louis to the United States. Colonial military installations, including Fort Belle Fontaine to the north of the city, were discontinued, and the city’s first formal municipal government began to take shape, with Chouteau appointed to some of the city’s early public offices. In 1804 St. Louis garnered significant attention as the point of westward departure for Meriwether Lewis and William Clark as they set out to explore the United States’ new frontier territory, ordaining the city as the “gateway to the west.”

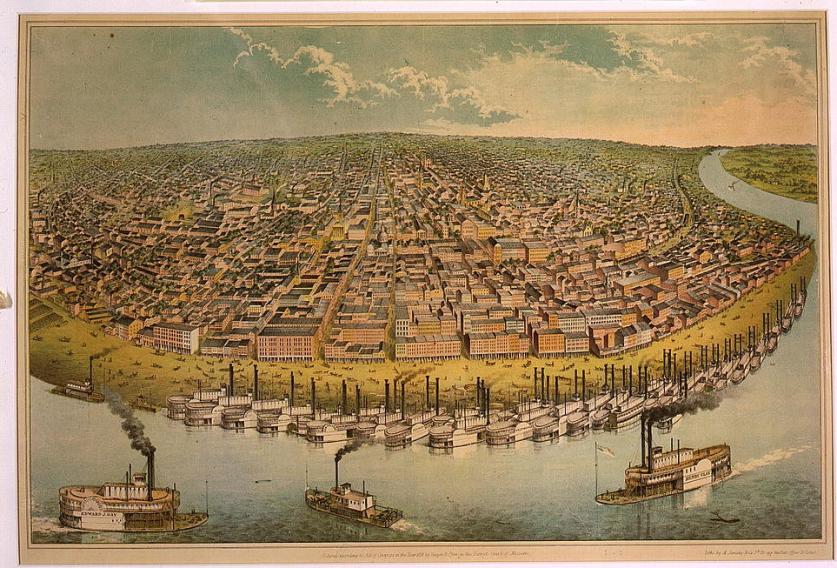

The first steamboat chugged into the St. Louis port in 1817. Occupying an advantageous position on an easily navigable port between eastern markets and westward territories of expansion, St. Louis was poised for prolific commercial growth. Within a year, as many as 50 steamboats at a time could be seen docked at the city’s levees. Growing in population and economic power, the Missouri territory sought statehood, though Missouri’s admission raised questions about the expansion of slavery that were debated in Congress for more than two years. The enslavement of Native, African American, and Creole people was still widely practiced in Missouri, and Southern states resisted efforts to restrict the practice as a condition of admission to the United States. Under the Missouri Compromise of 1820, Missouri was admitted as a slave state alongside the free state of Maine, and slavery was prohibited in the remaining territories included in the Louisiana Purchase, effectively establishing a boundary between slave and free states at the 36º30’ parallel. After Missouri’s statehood was granted, St. Louis became incorporated as a city in 1822, with William Carr Lane defeating Auguste Chouteau to become the city’s first mayor in 1823.

Fertile agricultural lands and profitable trading opportunities attracted legions of new settlers to St. Louis between 1820 and 1850, and the city’s population rapidly increased from approximately 4,500 to more than 77,000 citizens. Abundant exchange of goods and culture among British, French, Spanish, Creole, Native, enslaved, and settler populations fueled the city’s steady growth and diversified its economy. Waves of German immigrants arriving in the 1830s and 1840s found St. Louis to be fortuitously suited for the brewing of beer, due to its network of underground caves, shaped by the karst limestone bedrock, that could serve as naturally formed, suitably cooled storage rooms. With ample demand from bustling commercial ports, industry took off remaining one of the city’s most important facets of its economy to this day.

Population growth necessitated the expansion of the city’s boundary and fortifications. In 1826 a new military post was established at Jefferson Barracks to replace the earlier installation at Fort Belle Fontaine, and the city made a series of expansions to its western and northern boundaries between 1833 and 1845. When the city commons were sold for land expansion, a parcel of 30 acres was designated as a public square in 1836, and in 1851 established as the city’s first public park (Lafayette Park). Overcrowding and disease accompanied growth, and in 1849 the city suffered two tragedies that cost thousands of lives. A devastating 1849 fire that originated on a steamboat burned through the city’s congested riverfront commercial district and destroyed hundreds of residences. In the aftermath, city streets were widened, levees improved, and a new building code instituted. In the same era the city suffered several cholera outbreaks and subsequently drained many of its naturally occurring sinkholes, ponds, and rivers to reduce groundwater contamination, believed at the time to be a cause of illness. With expanding populations, burials were moved outside the city where new Catholic (Calvary Cemetery) and Protestant (Bellefontaine Cemetery; Greenwood Cemetery) burial grounds were soon established.

By 1850, German and Irish immigrants made up 50% of the population of St. Louis, and their arrival disrupted the profitability of slavery, as immigrant laborers often worked as cheaply as enslaved laborers but were legally able and willing to furnish their own housing and clothing. The first African American church in St. Louis, founded in 1835, allowed the community of free and enslaved African Americans in St. Louis to cultivate networks of information, support, and opportunity (Mary Meachum Freedom Site). As the profitability of enslaved labor declined, slave owners began to “hire out” enslaved persons to earn money by working on steamboats or neighboring farms. On occasion, enslaved people were able to save some of the wages they earned on additional work and over time accrue enough money to purchase their own freedom. In some cases, enslaved people who had lived in an adjacent free state, like Illinois, attempted to sue for their freedom. One such case, that of the enslaved Dred Scott and his wife Harriet, resulted in a Supreme Court decision ruling that the United States Constitution was not intended to grant rights of citizenship to Americans of African descent, a landmark case that contributed to the start of the Civil War.

A slave state since 1821, but economically and ideologically connected to the urban centers of the northeast, Missouri was an unclaimed and hotly disputed territory during the Civil War, with soldiers from the state fighting for both the Union and the Confederacy. St. Louis, at that time home to one of the nation’s largest military arsenals, was swiftly claimed by Union forces. The city avoided seeing battle but remained a strategically important supply depot for the Union Army throughout the war. Ulysses S. Grant, who had married Julia Dent of St. Louis in 1848 and settled at her family’s White Haven estate just outside the city, came out of military retirement to join the Union cause, leading that army to victory and eventually becoming President of the United States.

Following the war, the city initiated a series of public projects to improve infrastructure and enhance public space, with much of the work undertaken by immigrants who imbued the city with influences from their native Western and Eastern Europe. Throughout the city, new sewage systems were implemented, gas lighting installed, and privately donated and redesignated common lands dedicated as public parks. Merchant Henry Shaw, who immigrated from England to St. Louis by way of New Orleans in 1819, was inspired by the gardens of the great country house Chatsworth and the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, and donated land from his estate to establish the Missouri Botanic Garden in 1859 and the Victorian Gardenesque Tower Grove Park in 1868. German immigrant Maximilian Kern served as superintendent of public parks in the 1870s, utilizing his training at the German royal gardens at Stuttgart and Paris’ Tuileries Gardens to create public green spaces alive with ornament and classically proportioned. Kern worked often with the Prussian-born surveyor and engineer Julius Pitzman, who would go on to develop in St. Louis over three dozen resident-controlled, picturesque urban subdivisions, known in St. Louis as “private places,” that pioneered in America the concept of exclusive communities with communally shared space.

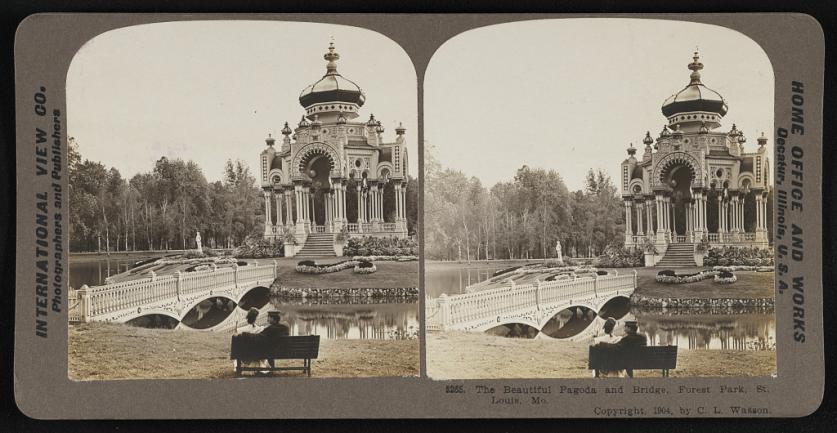

In 1876, the expansive Forest Park, designed by Maximilian Kern and encompassing more than 1,300 acres of woodland, open parkland, and pleasure grounds, opened to the public. Endowed with world-class public facilities, the city sought (for the second time) the opportunity to host the upcoming World’s Fair, having previously lost to Chicago. In 1899 their bid was approved, and the city’s leaders quickly set planning in motion for an exposition celebrating the centennial of the Louisiana Purchase. The Civic Improvement League, inspired by the City Beautiful movement, exploded in membership and worked diligently to ensure the city’s infrastructure and public amenities would be impressive in form and function to the legions of tourists who would visit St. Louis during the months-long exposition. George Kessler, a German immigrant trained in botany, horticulture, and city planning, was hired to design the 1,272 acres of fairgrounds in Forest Park. At the time of the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition, St. Louis was one of the country’s most vibrant cities. Already the world’s largest producer of beer, it now also dominated the market in the production of stoves, wagons, and shoes. The composer Scott Joplin, who moved to the city in 1901, brought the sounds of ragtime to St. Louis and gave birth to a music scene that would go on to produce legends such as Charlie Parker and Chuck Berry. The city’s bustling commercial corridors, freewheeling sounds and artists, generous public spaces, and elegant residential neighborhoods evidenced that its status had evolved from primitive colonial outpost to world-class cosmopolitan center.

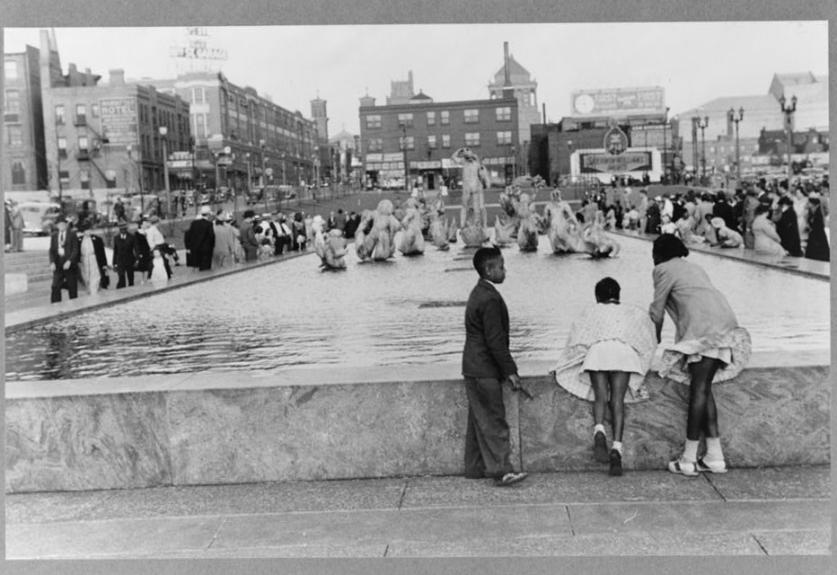

A century after its incorporation, St. Louis was the fourth largest city in the United States. As the city grew, efforts increased to improve and reorganize the city and were supported by municipal bond issues. Forest Park, mostly untended and overgrown following the World’s Fair, was redeveloped by George Kessler as a grand Picturesque municipal park home to several significant cultural institutions, including an art museum, zoo, and opera house. Kessler also supervised an attempt to extend the historic Kingshighway Boulevard to link all the city’s neighborhood parks, an ambitious undertaking that was only partially realized. The Beaux-Arts movement, which grandly made its introduction to the city with the Exposition Grounds, expanded its presence in St. Louis’ new educational (Washington University Danforth) and institutional (Soldiers Memorial Military Museum) campuses. In downtown, Harland Bartholomew planned a grand central mall (Gateway Mall) flanked by civic buildings, a vision that was incrementally completed over eight decades.

After a boom era, the Great Depression diminished businesses and civic investment in St. Louis, as in many other American cities. To stimulate land value in the suffering downtown business district, the city proposed the construction of a major attraction, the Jefferson Expansion National Memorial (now Gateway Arch National Park). The joint project, executed by the city and the federal government, was approved in 1935, and 40 downtown blocks were razed to make room for its construction. Progress lagged, hindered by World War II and the Korean War, but a design for a memorial by Eero Saarinen and Dan Kiley was finally chosen in a competition in 1948 and completed in the 1970s. The Modernism movement, exemplified by Dan Kiley’s and Eero Saarinen’s iconic, collaborative memorial gained a significant presence in St. Louis after World War II. Myriad designers, including Dan Kiley, Joe Karr, Emmet Layton, and Gyo Obata, a Japanese American who would go on to be a founding principal of the global firm Hellmuth, Obata, and Kassabaum (HOK), disrupted the Victorian and Beaux-Arts character of the city with their ambitious public and private projects (Forest Park Community College, Climatron).

In the mid-twentieth century, many white and middle class African American families left the city of St. Louis for its numerous suburbs (Carrswold), further endangering the endurance of the city’s historic fabric. The fervor for progress and transformation resulted in the demolition of many of the city’s historic, predominately African American neighborhoods, including Mill Creek Valley and DeSoto-Carr. Modernist superblock housing structures attempted to realize the mid-century vision of centralized urban living and were built to accommodate both the professional class (Mansion House Center) and working class residents displaced by urban renewal (Pruitt Igoe). Many in the latter category were built north of Delmar Boulevard, an unofficial boundary for racially restrictive residential covenants. Unlike its neighbor East St. Louis, Illinois, which experienced a violent race riot in 1917, St. Louis avoided violent racial confrontations during the Civil War, Reconstruction, and Civil Rights eras, but explicit and implicit segregation policies and racial disparities continue to shape the city’s culture and geography well into the 21st century.

A north-south highway slated to displace the newly designated Lafayette Square historic district kickstarted a passionate, community-led preservation movement that emerged in the 1970s to counteract the abandonment and demolition of the city’s downtown and historic resources (Lafayette Park, Laclede’s Landing). Successful public-private partnerships galvanized interest in historic preservation to advocate for an array of St. Louis landscapes to be documented as heritage resources by the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) and designated as National Historic Landmarks with “Significance in Landscape Architecture” (Missouri Botanical Garden in 1976 and Tower Grove Park in 1989). In the 1980s non-profit organizations dedicated to historic urban parks were founded including Forest Park Forever (1986) and Friends of Tower Grove Park (1989), each with a dedicated focus to maintain, improve, program, and raise the visibility and value of the city’s historic parks which for decades had suffered from deferred maintenance. Today, these dedicated stewards extend to the city’s neglected historic urban landscapes (the Ville, Dutchtown).

In surrounding counties, groups similarly mobilized to preserve, protect, and interpret the natural resources, historic character, and cultural traditions of the regions unique landscape heritage (Great Rivers Greenway, Riverfront Trail) and, thanks to the efforts of Magnificent Missouri, extending for 100 miles along the Missouri River Valley (Katy Trail, Country Store Corridor).

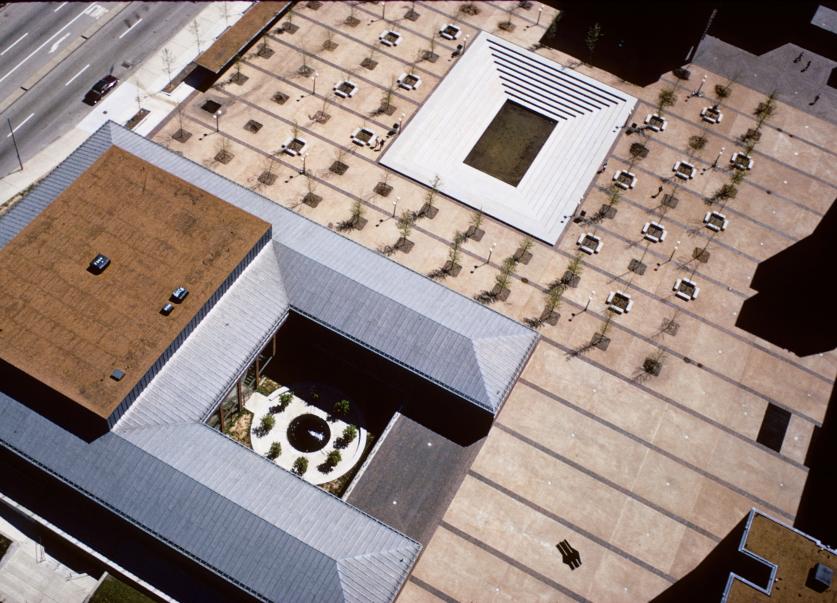

Amplified in part by the creation of Washington University’s Sam Fox School of Design and Visual Arts in 2006, St. Louis has experienced a renewed investment in landscape architecture that builds upon the city’s diverse landscape legacy by increasing accessibility and enhancing connectivity (Gateway Arch National Park, Katherine Ward Burg Garden) while also humanizing and enlivening the public realm (Pulitzer Arts Foundation, Citygarden, Ellen S. Clark Hope Plaza). For centuries this advantageously positioned river valley has attracted people from all around the world. The region has had many iterations: a fulcrum for westward expansion; a center for trade and commerce; a cultural hub; and more. All these facets are reflected in a unique, varied, rich, and frequently surprising body of cultural landscapes.