Themes

The sites, designers, and historical moments included in this online guide were chosen, in part, because they represent a variety of themes that are important to communicating the breadth of cultural landscapes associated with African Americans. Interrelated and multifaceted, those themes are briefly discussed below. Because the themes are complex, these essays should not be considered comprehensive. Rather, they are overviews—intentionally loose and broad—intended to introduce major concepts, provide basic background, and inspire further research.

From the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries hundreds of thousands of Africans were forcibly transported first to North American colonies and then the United States. Their descendants were held in bondage through the American Civil War (the 1860 U.S. Census counted approximately four million enslaved people). Enslaved individuals were treated as chattel (portable personal property) that could be inherited, sold, or transferred. They were forced to perform labor or services under threat of physical or emotional mistreatment, separation from family, or death. While chattel slavery was the key economic structure in the development of American agriculture, its impact broadly permeates American history.

In 2022, the NPS recognized the need for a specific theme study devoted to this institution of forced labor and bondage that lasted more than 250 years. The need for understanding this historic context is foundational to its stewardship.

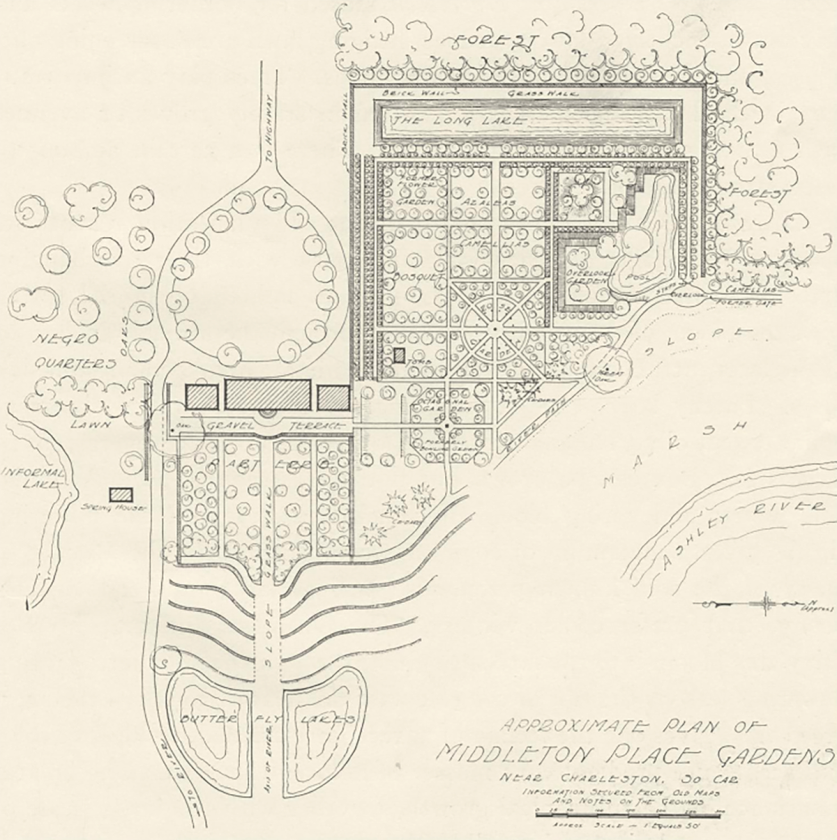

Although TCLF’s expansive What’s Out There database includes more than 50 landscapes created largely by the enslaved, including, Middleton Place, Charleston, S.C.; Monticello, Charlottesville, VA; and Oak Alley Plantation, Vacherie, LA, additional research is required to understand what remains of their contributions and how/if this is being interpreted for the public. Based on available information at this time, this guide revisits sites that through their commitment to research (archival and archaeological) and analysis, along with project work (reconstructed structures and landscape features, expanded site interpretation, and introduction of new commemorative features), have aimed to convey a more complete and authentic site narrative that better reflects the role enslaved African Americans had in shaping these historically significant cultural landscapes.

Impacts of African Cultures on the American Landscape

From the earliest settlements of non-indigenous peoples in what would eventually become the United States European and African cultural, technological, and social traditions melded, shaping a uniquely American culture. By 1839, 2.3 million (eighteen percent) of the 12.8 million people in the United States were of African descent. Through daily activities and interactions, Africans and their descendants profoundly informed American culture, influencing visual arts, music architecture, foodways, and language. African words, phrases, and names permeate American English, evidenced by places such as Suwanee Old Town, FL and Nicodemus, KS. African culture similarly influenced how cultural landscapes were shaped and cultivated.

During the period of enslavement, whether with permission or in acts of resistance, African Americans congregated in public spaces to engage in practices and rituals derived from West and Central African antecedents, including dance, instrumentation, song, spirituality, and other forms of cultural expression. Trees and other natural features often stand as living witnesses to collective moments of joy, spirituality, and grief enacted in these public spaces.

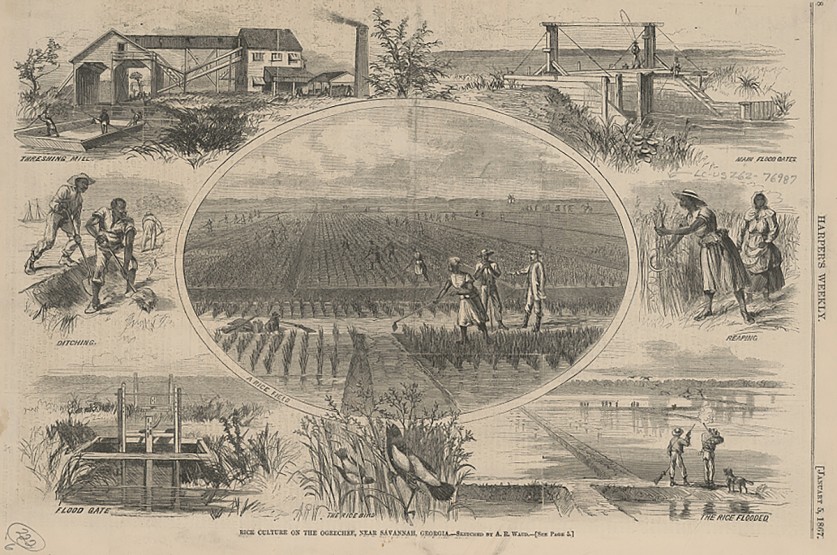

Several southern plantations became dependent on people with direct or inherited knowledge of African agricultural practices and technologies. In the eighteenth century people were forcibly taken from rice growing regions of West Africa to cultivate the crop in America. The tidal floodplain system used in the Senegambia region of Africa, for instance, was reproduced on plantations in South Carolina, Georgia, and Louisiana. Knowledge and technologies informed agricultural practices that persist today in Gullah/Geechee culture, which stretches from the Carolinas to northern Florida.

West African funerary practices are also manifest at surviving burial grounds throughout the eastern and southern United States. Such practices include adorning or placing seashells at burial sites and orienting the interred according to the cardinal directions.

Entries in this guide include: African Burial Ground National Monument, New York, N.Y.; Congo Square, New Orleans, LA; and Hog Hammock, Sapelo Island, GA.

Between 1780 and 1865, there was an increase in the number of people willing to assist self-emancipated individuals, and in raising public awareness of their efforts. By the 1830s the act, either spontaneous or organized, to assist people held in bondage, self-emancipated individuals, and those seeking to escape enslavement, became commonly known as the “Underground Railroad.” During the period of greatest activity (1830 to 1861) the Underground Railroad relied on loosely organized networks that followed routes both naturally occurring (e.g. streams, rivers, etc.) and constructed (e.g. roads, trails, etc.). Freedom seekers, traveling alone or accompanied by an accomplice or guide, found haven at stations (structures or sites) located along the routes.

Concurrent with the growth of the abolitionist movement (beginning in the 1730s), small groups of self-emancipated individuals successfully established settlements in remote locations called maroon communities including Virginia’s Great Dismal Swamp, the Okefenokee Swamp straddling the border of Georgia and Florida, and the Florida Everglades.

Surviving cultural landscapes related to the Underground Railroad include stations, sites associated with prominent individuals or abolitionists, rebellion sites, properties associated with documented cases of self-emancipation, and maroon communities. Examples include Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Monument, Church Creek, MD; Mary Meecham Freedom Crossing, St. Louis, MO; and, the Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge, Cambridge, MD.

During a transformative era from 1861 (the onset of the Civil War) to 1900 the United States addressed the integration of African Americans into social, political, economic, and labor systems and attempted to rebuild and reunify the divided nation.

Newly emancipated African Americans strove to own land and while some gained temporary access to 40-acre plots along the Carolina and Georgia coast, most worked for or rented land from white landowners. The system of sharecropping emerged, in which landlords allowed a tenant to use land in exchange for a share of the crop.

Following the Military Reconstruction Acts of 1867 and the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870, emancipated African American men were able to participate in politics and vote. Enfranchisement coupled with the transformation of southern labor and law, inspired a violent counterattack by individuals and vigilante groups. To avoid emotional and physical terror, some African Americans relocated north and west, establishing settlements or enclaves where they could govern independently. Among those included in this guide are: Nicodemus National Historic Site, KS; the Village of Brooklyn, IL; and Freedmen’s Town, Houston, TX.

Simultaneously, there was a pressing need to establish a new social structure as well as societal institutions that promoted the civil and political rights of formerly enslaved people. Institutions of higher education now referred as Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU) and other institutions were founded throughout the United States (though mostly in the South). The early twentieth century saw chapters of exclusively African American fraternities and sororities established on these campuses. Examples include: Fisk University, Nashville, TN; Howard University, Washington, D.C.; and Alcorn State University, Loreman, MS.

The ten-year period from 1954 to 1964 saw some of the most significant developments in Civil Rights history and is defined by the NPS as the Modern Civil Rights Movement. This includes the signing in 1957 by President Dwight D. Eisenhower of the first civil rights bill since Reconstruction, creating the independent U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, along with the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education (mentioned below) and the 1964 Civil Rights Act (also mentioned below). Parks, streets, and other public open spaces served as the staging grounds for some of the movement’s most critical demonstrations and peaceful protests, including the Birmingham Campaign (1963), and the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (1963). This period had a profound impact on the southern urban landscape that survives to this day.

As crucial and impactful as the period from 1954 to 1964 was, numerous consequential events took place before and after that decade-long time that aimed to grant African Americans equal rights under the law and to end racial segregation and exclusion.

The struggle to end chattel slavery and racial inequities began in the 1730s with a Quaker-led abolitionist movement. Decades later, the words of Thomas Jefferson in the Declaration of Independence asserting that “all men are created equal” were adopted by abolitionists to condemn the institution of slavery and continued to do so leading up to the Civil War.

Passed during Reconstruction, the Thirteenth (ratified 1865), Fourteenth (ratified 1868), and Fifteenth (ratified in 1870) Amendments to the U.S. Constitution abolished slavery, guaranteed equal protection under the law and due process, and gave all male American citizens the right to vote regardless of their “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” However, the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) derailed that progress by permitting racial segregation of public spaces as long as they were equal to the facilities for whites, the doctrine known as “separate but equal.”

In 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802 prohibiting discrimination in the defense industry. It was spurred by a meeting between First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, cabinet members, A. Philip Randolph, president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, and other African American leaders who threatened to bring tens of thousands of protestors to the White House unless their demands were met. The movement demonstrated the effectiveness of grassroots African American politics and that an African American-led mass movement of nonviolent protest could mobilize for civil rights. Seven years later, in July 1948, President Harry S. Truman, issued Executive Order 9981 desegregating the U.S. Armed Forces. (“During World War II, the Army had become the nation’s largest minority employer.”)

Examples include: Kelly Ingram Park, Birmingham, AL and Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historical Park, Atlanta, GA.

The 1954 unanimous U.S. Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education mandated racial desegregation in public schools and overturned the “separate but equal” doctrine. As the NAACP Legal Defense Fund notes, “Brown v. Board of Education itself was not a single case, but rather a coordinated group of five lawsuits against school districts in Kansas, South Carolina, Delaware, Virginia, and the District of Columbia.” The ruling’s impacts changed the face of public education across America. Sites associated with this historic milestone include: Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Park, Topeka, KS; and, Little Rock Central High School National Historic Site, AR.

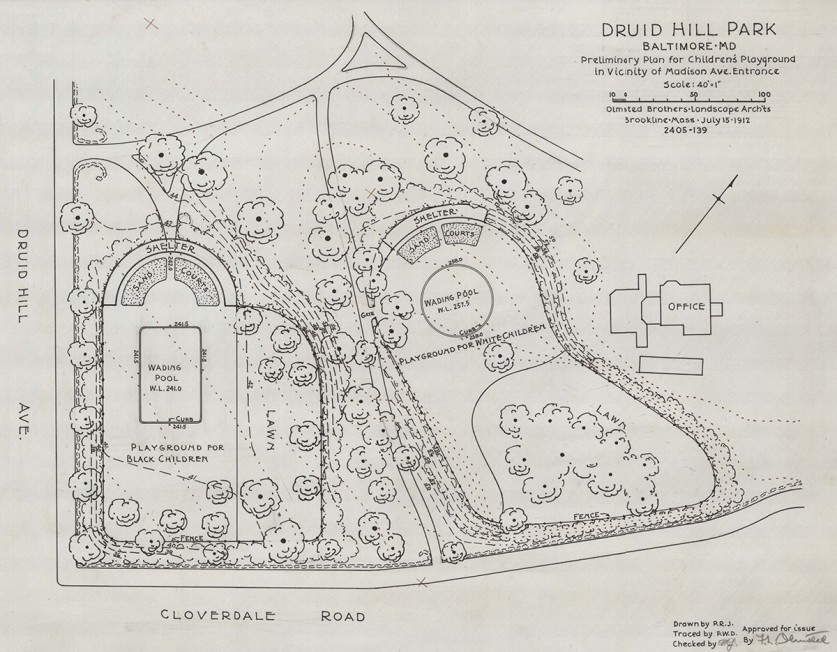

An integral part of the historic context for the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson and “prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex or national origin,” this specific theme focuses on the physical separation of the races in public accommodations.

The idea of “separate but equal” was not just for buildings, it extended outdoors to include public parks and open spaces, swimming pools, and other park amenities. So limiting was this issue of accommodations for African Americans that from 1936 to 1966, “The Negro Motorist Green Book” was published annually to help African American travelers locate safe lodging, restaurants, gas stations, and accommodations.

This theme encompasses the following: Chickasaw Park, Louisville, KY; Druid Hill Park Memorial Pool, Baltimore, MD; Fairground Park, St. Louis, MO; and, John Chavis Memorial Park, Raleigh, N.C.

In addition to the theme studies identified by the NPS, and methods for recording history, this guide aims to highlight contemporary efforts by landscape architects, artists, architects, historians, interpreters, and others to redefine notions of commemoration beyond traditional memorials, historical markers, and interpretive/wayfinding signage.

Parallel with the surge in scholarship outlined in earlier themes, there has been a burgeoning movement to address the often messy and complicated histories associated with many African American cultural landscapes. These memory-laden sites have been historically devalued, forgotten, confiscated, or erased. Efforts to spatialize these public memories, buoyed by a groundswell of community-based collective actions, have ushered in a new era of storytelling, remembrance, and recognition.

Examples include: Black Lives Matter Plaza, Washington, D.C.; The National Memorial to Peace and Justice, Montgomery, AL; and Rondo Commemorative Plaza, St. Paul, MN.

Elevating Designers and Shapers

This guide makes visible a number of African American designers, place makers and shapers who created many of the cultural landscapes highlighted, including former estates and plantations, college campuses, institutional grounds, and site-specific artwork.

From the seventeenth century until the 1860s African Americans shaped the nation, clearing forests, dredging swamps, cultivating and harvesting crops, and many other related activities. For example, during this era of enslavement, African American gardeners and horticulturists, both emancipated and enslaved, contributed to the development of numerous plantations and estates.

Pioneers include Izadod Conner (1779-unknown), James F. Brown (1793-1868) and Alexander Gilson (1824-1889).

While African Americans were afforded opportunities to attend and acquire degrees from institutions of higher education in the late nineteenth century, there were few opportunities for African Americans to make a career in landscape architecture or architecture. Many of those who were successful in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries contributed to the development of HBCUs, designing structures and planning and laying out entire campuses. African Americans designers continued to influence institutions of higher learning throughout the twentieth and early 21st centuries, serving as campus landscape architects and architects, master planners, instructors, and heads of programs. Examples include David Augustus Williston (1868-1962), Albert Irvin Cassell (1895-1969), and Edward Lyons Pryce (1914-2007) and Perry Howard (1952-). Nevertheless, as of 2023, only 0.8 percent of the U.S. landscape architects are African American men and 0.3 percent are women.