New York City's Landscape Legacy

The What’s Out There Cultural Landscapes Guide to New York City is the second in an ongoing series of guides being produced as a collaboration between The Cultural Landscape Foundation (TCLF) and the National Park Service (NPS). Launched in March of 2016, the inaugural guide in the series covers Philadelphia, just 100 miles southwest of New York. These two Mid-Atlantic cities, both planned in the seventeenth century, continue to be important urban centers.

The important position that New York would come to occupy in the history of urbanism could not have been foreseen in 1609, when the British explorer Henry Hudson was engaged by the Dutch to find a faster route to the Orient. During this voyage, Hudson accidentally arrived at one of the world’s three greatest natural harbors—an expansive, sheltered bay off the Atlantic Ocean that came to serve as a gateway to North America, while also proving to be the perfect location for a city, New Amsterdam.

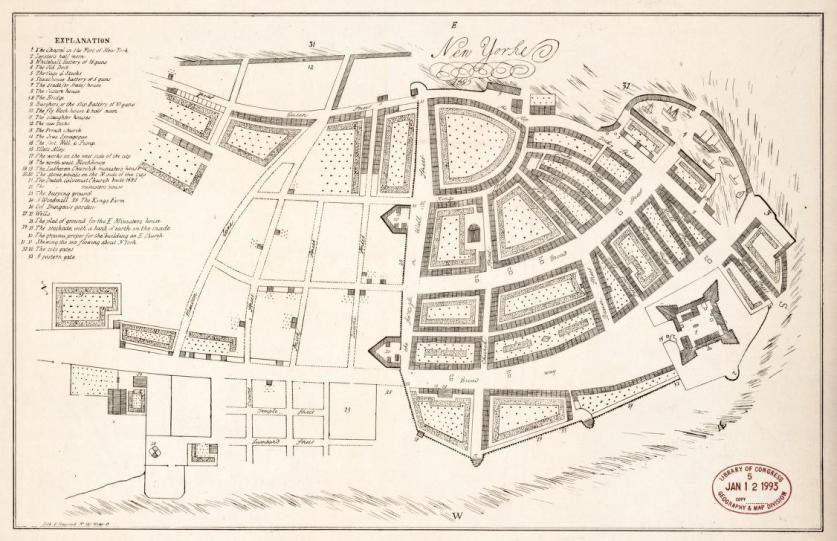

By 1664, Dutch rule had come to an end (except for a brief period from 1672 to 1674) and within a year’s time, the city was renamed New York by the English. With this transition came the city’s first municipal oversight for the entire island of Manhattan and a surge in manufacturing and trade. By the turn of the next century, the city expanded to the East River, and the first large-scale subdividing began downtown, on a track of land just north of Maiden Lane. By mid-century, several land development schemes formalized the rectangular street system of the city, while the city’s first public park, Bowling Green, was established by a resolution of the Common Council on March 12, 1733. Commercial growth and land development continued apace until the city was occupied by British troops. During this time (1776 and 1778), population trends reversed -- the latter the result of fires that swept through the city.

Following the Revolutionary War, the city became the temporary capital of the new nation. Land formerly owned by British loyalists (e.g. the DeLancy subdivision) came back into public ownership. As a result of this land sale, which generated much needed revenue, a new open space, Hudson Square, appeared on maps for a short period of time. But this small public space eventually vanished. The planning actions employed at this time, according to historian John Reps, would inaugurate “a series of events that culminated in a street plan for most of the Island of Manhattan.”

The turn of the next century ushered in many cultural shifts: the emancipation act was passed in 1799, leading to the abolition of slavery by 1824 in New York State (the first state to do so); Alexander Hamilton was killed in 1804 in a duel with rival Aaron Burr (his death was mourned by thousands in the largest funeral procession in the city's history); and, in 1807, inventor Robert Fulton launched the world's first practical steamboat off the West Side of Manhattan. City Hall Park, which had been improved with trees and grass sometime after 1784, saw the cornerstone laid for a new City Hall in 1803, while its public common came to be known as "The Park."

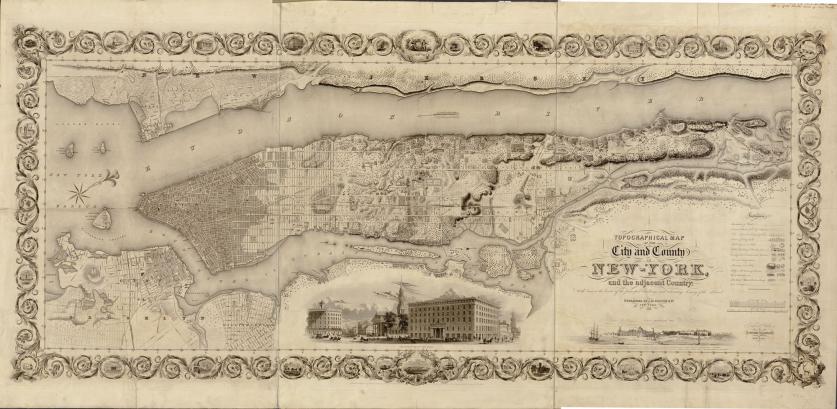

By the next decade, De Witt Clinton (who served as both the city's mayor and the state's governor), proposed two audacious plans: one resulted in a re-design of the city into its famous geometric "grid" of intersecting avenues and streets, while the other resulted in the construction of the Erie Canal (completed in 1825). The impacts of these endeavors were lasting and significant, supporting the rational and organized growth of the city and connecting it with America’s heartland. As a result, New York City became the economic center of the young nation.

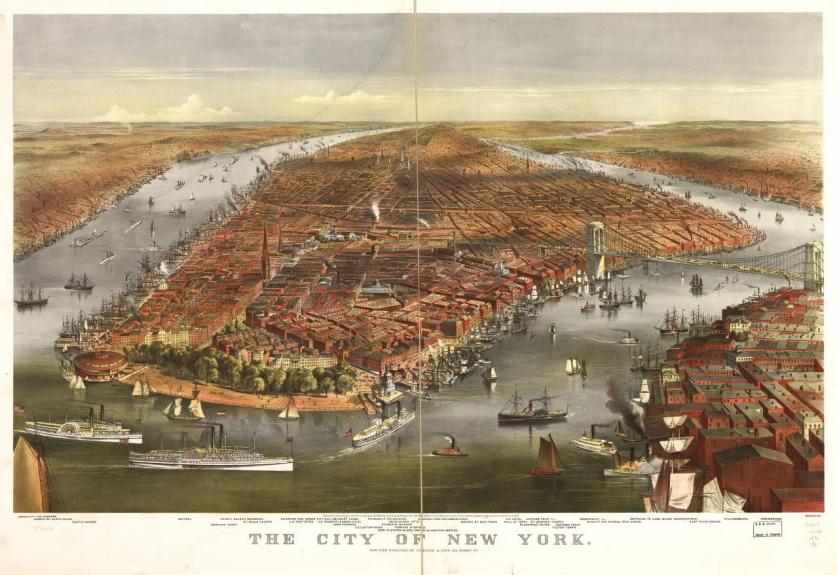

As New York grew both physically (to now include Brooklyn, which was incorporated as a borough in 1834, and had its own plan for neighborhood parks) and symbolically, there was an increasing demand for civic assets worthy of a great city. By the mid-nineteenth century, nature and wilderness were rapidly disappearing in the region, and there was a general sense of overcrowding. And although the city had its share of parks and public spaces, including Battery Park, Bowling Green, City Hall Park, Madison Square, Reservoir Square (now Bryant Park), Union Square, Washington Square, and Washington Park in Brooklyn (now Fort Greene Park), not to mention cemeteries and burial grounds both small (Trinity Church) and large (Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn), it could not boast of a major urban park in the European tradition, such as Birkenhead Park in Liverpool, England, for example.

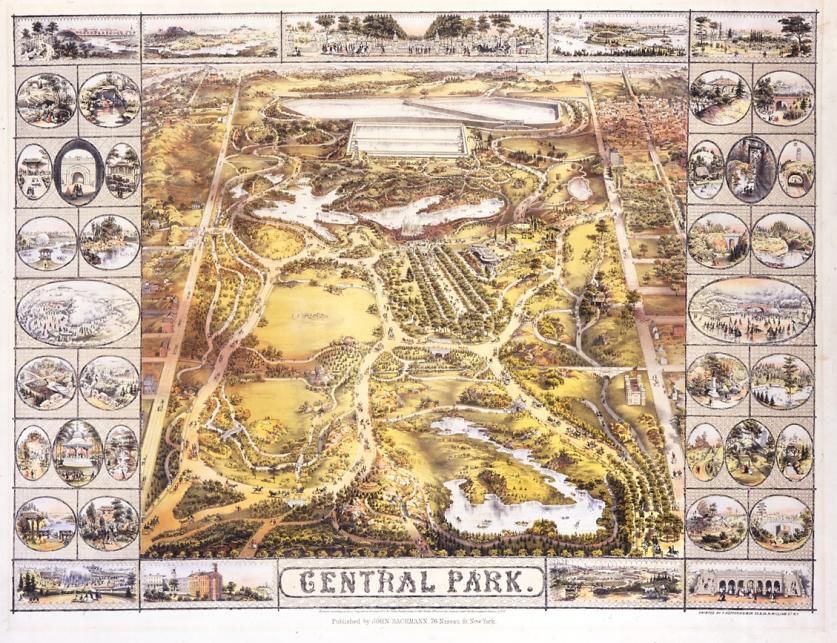

By 1850, Manhattan’s population had swelled to more than 500,000 (from a mere 97,000 in 1811) to become an exploding metropolis, but its public squares measured a paltry 63 acres. Two years later, after significant public discourse and debate, the site for Central Park was selected, and by 1857 the New York State Legislature created the Board of Commissioners of Central Park. The following year, on April 28, the award-winning plan for Central Park, by Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., and Calvert Vaux, titled "Greensward," was selected by the Board of Commissioners. By that summer, select sections in the park’s southern corner would be open to the public.

Brooklyn, which by 1859 had a population of nearly 280,000 (up from 48,000 in 1840), created its own Board of Park Commissioners, which engaged Olmsted and Vaux the following year to design the 585-acre Prospect Park. Here the designers got to define the park's size, shape, and location, while also supervising its construction. Building on Central Park’s success, the two men were able to extend the idea of a park to a truly metropolitan scale. As detailed in their 1866 report titled “Suburban Connections,” the idea of the parkway and a park system was born with Ocean and Eastern Parkways, which were built out in the 1870s.

The 1880s and 1890s saw the continuation of park acquisition and park making throughout the city. Other picturesque parks were built, including Morningside Park and Riverside Park in Manhattan, and Forest Park in Queens. Meanwhile the State Legislature passed the Small Parks Act of 1887, a pioneering law that enabled land acquisition for new small parks in overcrowded neighborhoods. This resulted in a number of parks, including Mulberry Bend (now Columbus Park), Hudson (now James J. Walker Park) and De Witt Clinton. The following year, in 1889, the city took title to St. Mary's, Claremont, Crotona, Bronx, Van Cortlandt, and Pelham Bay Parks, as well as the Bronx, Pelham, Crotona, and Mosholu Parkways. For the Bronx, this collection brought 3,495 acres of new parkland.

The turn of the century ushered in City Beautiful design principles, reflecting the influence of the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition held in Chicago. It was the end of an era for park-making in the Picturesque tradition. This new period is best illustrated by such parks or park features as Grant's Tomb or the Soldiers and Sailors Monument in Riverside Park in Manhattan; Grand Army Plaza and the Prospect Park Boathouse in Brooklyn; or the master plan of Ellis Island by the New York architectural firm of Boring and Tilton.

In 1898, the Boroughs of Staten Island, Brooklyn, and Queens were incorporated with the city to form "Greater New York." At the time, this was the world's second largest city (after London) with a population of 3.5 million.

With the boroughs united as one city, during the first quarter of the twentieth century, progressive ideals of social activism and political reform took hold. In the public realm, this resulted in leisure activities where families required healthy, wholesome environments, which lead to the idea of smaller parks and playgrounds, including Seward Park, which, in 1903, became the first municipal park furnished as a permanent playground. Others followed, including Thomas Jefferson, St. Gabriel's (now St. Vartan), and East River (now Carl Shurz), mostly designed by Samuel Parsons, Jr.

However, it was not until the 1920s that grand, municipal-scale planning advanced, enabled by the Parks Commissioner Robert Moses. Backed by New Deal-era funding and responding to city streets choked by a half a million new motor vehicles, Moses commissioned the construction of parks, highways, zoos, swimming pools, civic centers, sports stadiums, exhibition halls, 13 bridges, 658 playgrounds, 416 miles of parkway, 150,000 units of public housing, and the 1964-65 World’s Fair. Park acreage under Moses increased from 14,000 to 34,673 acres. Among his most noteworthy projects are Jacob Riis Beach in Brooklyn, Jones Beach State Park in Long Island, the Belt, Grand Central, Cross Island, and Henry Hudson Parkways, as well as a number of outdoor pool complexes.

On a parallel track with these municipal-scale developments, the early twentieth century witnessed the rise and maturation of historic preservation in the United States. The National Park Service was created in 1916, and with the passage of the Historic Sites Act of 1935, the responsibility of preserving and interpreting buildings, landscapes, and objects that were emblematic of American heritage fell upon the NPS. These events paralleled the rise of American suburbs, made possible by the increased federal funding of highways and home loans. As a result, many affluent urbanites relocated to the suburbs.

If Moses, along with his consulting landscape architects Clarke & Rapuano, ushered in the Modernist era for landscape architecture in the city, innovation also took hold with the creation of new plazas (Lincoln Center), cantilevered walkways (Brooklyn Promenade), vest pocket parks (Paley and Greenacre parks), and adventure playgrounds (designed by M. Paul Friedberg and Richard Dattner). Complementing these efforts, grants from the Land and Water Conservation Fund in the 1960s and 1970s improved several parks, playgrounds, and amenities in neighborhoods throughout the city, including St. Catherine’s Park in Manhattan, St. Mary’s Park in the Bronx, and the Playground for all Children in Queens.

Perhaps the single biggest increase in the city’s parkland came in 1972 when the 26,607-acre Gateway National Recreation Area (GNRA) was established. Rich in ecological and cultural assets, the park was one of the first to be purchased with federal funds, rather than being donated or re-appropriated from federally held lands. The GNRA also signaled a new and significant direction for the NPS—a large eastern park was added to a portfolio otherwise characterized by large parks concentrated in the West and Mountain states, where Federal lands were typically held.

Today, New York City has an unrivaled and diverse collection of National Parks, cultural properties, and municipal parks, including a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the Statue of Liberty. Throughout the city, there are 268 National Historic Landmarks (e.g. New York Botanical Garden and Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx, Central Park and Rockefeller Center in Manhattan, and Governor’s Island National Monument); 5,630 National Register of Historic Places designated properties (including the Bronx Zoo and the Bronx River Parkway, the Liz Christy Community Garden in Manhattan, and the Alice Austen House in Staten Island); and more than sixteen million annual visitors to the National Parks. In addition, the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation manages more than 1,700 parks, playgrounds, and recreation facilities, not to mention 23 historic houses across the five boroughs, all totaling more than 30,000 acres.

This cultural landscapes guide aims to bring to life the rich diversity and interconnectedness of this unrivaled, shared heritage.