San Antonio's Landscape Legacy

San Fernando de Béxar

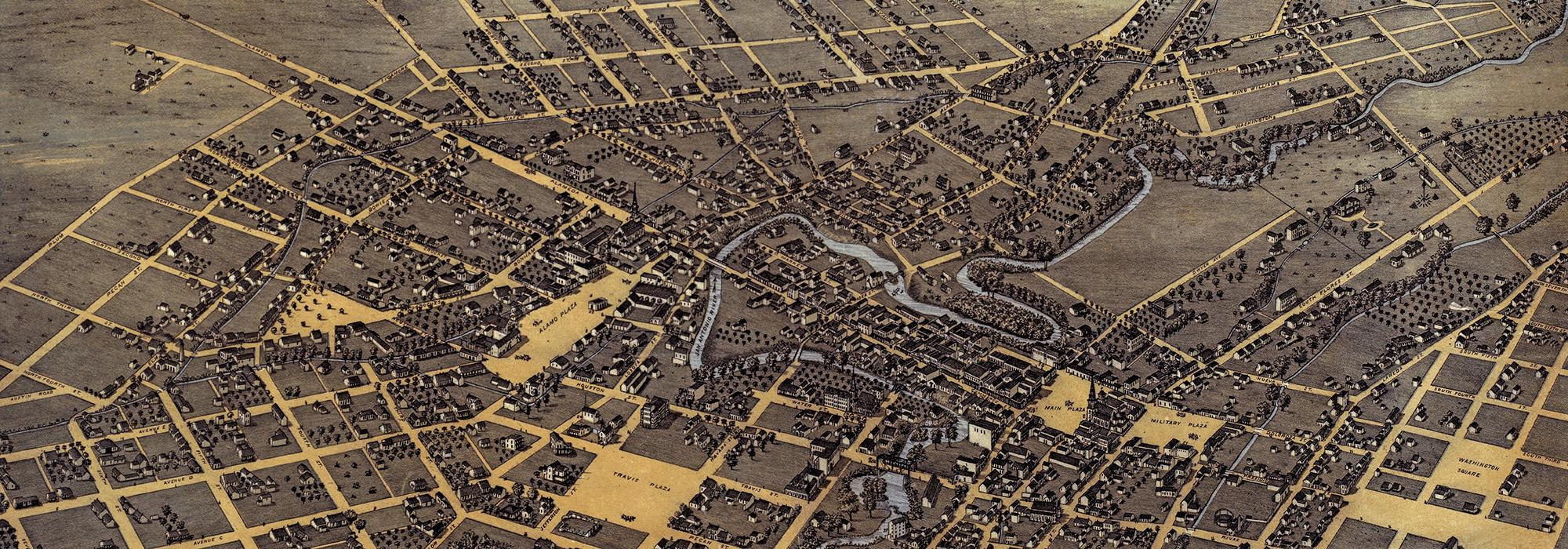

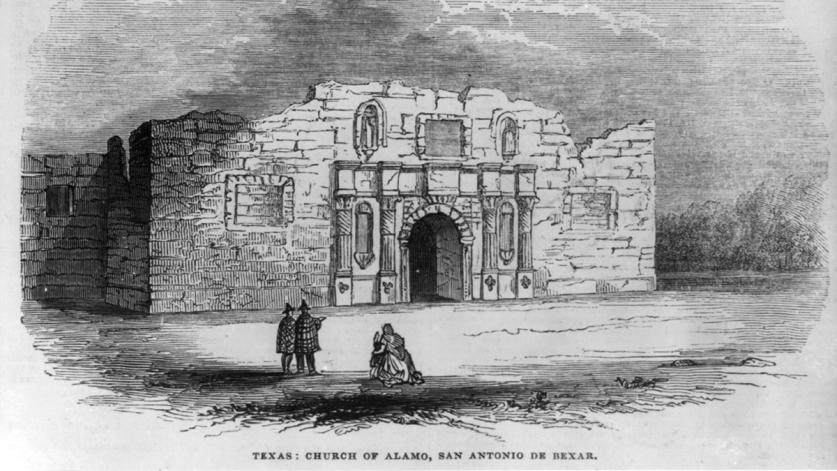

Although European explorers had been aware of the vast wilderness that comprises present-day Southern and Central Texas since the sixteenth century, it was not until 1718 that a Spanish presidio (fortified military settlement) was established along the banks of a prominent river there. The lush, riparian landscape was a prime location for a settlement, and in 1731 Villa de San Fernando was founded on a small hill just east of the presidio, between the San Antonio River and San Pedro Creek. Collectively known as San Fernando de Béxar, the villa, presidio, and accompanying mission (Misión de San Antonio de Valero, aka The Alamo) laid the groundwork for what would become the City of San Antonio.

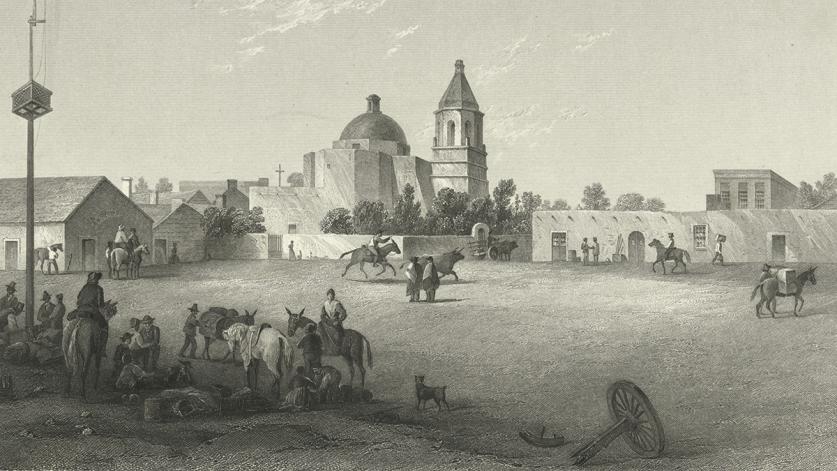

Today, San Antonio’s approximately three-acre Main Plaza, encompassing the original villa site, continues to serve as a focal point of downtown. Following Spanish colonial urban-planning principles, important structures, including the church and the seat of government, were arranged around the plaza in the eighteenth century. Originally a flat square of packed earth, the public space was improved with sidewalks and plantings in second half of the nineteenth century, and a small parish church along the western edge of the plaza was replaced in 1870 by the San Fernando Cathedral (listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1975).

Beyond the cathedral to the west of the plaza lies Military Plaza, established in 1722 as a parade ground and open-air market for soldiers garrisoned at the presidio. It remained an open square until 1891 when City Hall, designed by architect Otto Kramer, was constructed at its center, occupying most of the site. The last surviving remnant of the presidio, the Spanish Governor’s Palace (listed in the National Register of Historic Places and designated a National Historic Landmark in 1970) is connected to the west side of the plaza by a pathway shaded with staggered live oaks. Completed in 1749, this colonial adobe structure originally served as the comandancia (residence) for the commanding officer of the presidio.

In 1729 the Spanish monarchy designated a commons centered around a natural spring flowing from a terraced outcropping of limestone approximately two miles to the northwest of the presidio. This critical water source had been discovered by Spanish explorers in 1709, although it was known to Native peoples as early as 9000 B.C. The 46-acre square, which was later named San Pedro Springs Park, is considered among the oldest public parks in the United States. Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., would describe the site in March 1854 as follows:

There are, besides the missions, several pleasant points for excursions in the neighborhood, particularly those to the San Antonio and San Pedro Springs. The latter is a wooded spot of great beauty, but a mile or two from the town, and boasts a restaurant and beer-garden beyond its natural attractions. The San Antonio Spring may be classed as of the first water among the gems of the natural world. The whole river gushes up in one sparkling burst from the earth. It has all the beautiful accompaniments of a smaller spring, moss, pebbles, seclusion, sparkling sun- beams and dense overhanging luxuriant foliage. The effect is overpowering. It is beyond your possible conceptions of a spring.

The establishment of a military base and civic center encouraged missionaries throughout the region to relocate their missions to the growing settlement. Many of the early settlements in Southern Texas, including the Spanish missions, initially comprised temporary structures, but when Missions Concepción, San José, San Juan Capistrano, and Espada were relocated along what would come to be known as the San Antonio River, permanent church structures, living quarters, and utilities were erected. While much historic fabric has been removed over three centuries, the four original churches remain. The extant structures of the southernmost missions, Espada and San Juan, are situated within a predominantly rural setting and include a combined 200 acres of labores (fields) and historic acequias (irrigation systems), of which the Espada acequia is still in use by neighboring farming communities.

Nineteenth-Century Urban Development

The early nineteenth century was a period of unrest in the region, with near-constant strife among the Mexican, Spanish, and Native American populations. When Texas was admitted to the Union in 1845, the population of San Antonio was fewer than 1,000 people. However, the second half of the nineteenth century saw rapid growth in the city. The immigrant population was expanding, and real estate along the river and south toward the missions was in high demand. New neighborhoods appeared, and already existing residential districts expanded dramatically. Initially inhabited by Spanish settlers as early as 1768, the La Villita neighborhood became a hub for German, Swiss, and French immigrants throughout the nineteenth century. Many of the buildings constructed there in the Spanish Colonial and Mission Revival styles would later be restored by the National Youth Administration under the guidance of architect O’Neil Ford, and today the area is one of San Antonio’s most intact historic districts.

In 1877 San Antonio acquired its first street cars, spurring economic and commercial growth in the wake of an increasing population. This new technology provided connectivity between neighborhoods and encouraged development beyond the immediate downtown area. In 1887 George Russ, F. H. Brown, and W. P. Anderson of the West End Town Company purchased 1,000 acres of rural land known as Maverick’s Pasture to develop a streetcar suburb three miles northwest of downtown San Antonio. Two years later, they constructed a dam across Alazan Creek, creating a large lake with a small casting pond at its southeast corner, at the terminus of the line. In 1919 the lake and its surroundings were donated to the city for the establishment of a public park, subsequently named Woodlawn Lake Park.

From the Twentieth Century to the Tricentennial

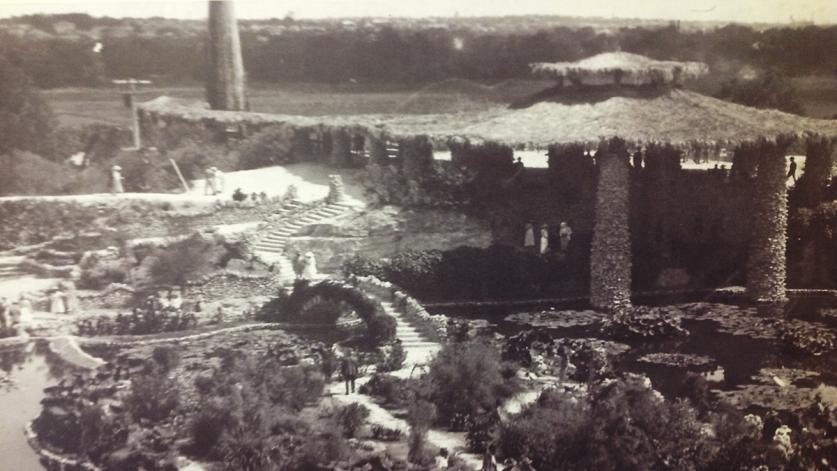

By the turn of the century, just 50 years after Texas had been admitted to the Union as the 28th state, San Antonio’s population had increased to more than 53,000 people. As the city’s ranks swelled, its leaders responded to the need for more civically minded public space. In 1899 George W. Brackenridge of the San Antonio Water Works Company donated 199 acres to the city for recreational use. Situated just below the headwaters of the San Antonio River, the site had been a gathering place since the time when Native Americans lived in the area. In the sixteenth century, Spanish settlers established a sophisticated water system there, remnants of which remain today. Brackenridge Park’s first improvements were led by City Park Commissioner Ludwig Mahnke (a friend of Brackenridge who had encouraged him to donate the land), who established a wild-game preserve and developed curvilinear paths and drives that wound through the trees along the river.

To the east of Brackenridge Park, on the east bank of the San Antonio River, Miraflores was derived from a fifteen-acre plot purchased in 1921 and developed over two decades as the private garden of Aureliano Urrutia, a renowned physician who fled to San Antonio in 1914 during the Mexican Revolution. The park features several works by sculptor Dionicio Rodriguez, whose signature faux bois (from the French for “false wood”) pieces can also be found elsewhere in the city.

Also in 1921, following a catastrophic flood that killed 50 people, plans were made to control the San Antonio River by creating an upstream dam and a bypass for a large bend in the river. According to the plan, the bend would then be paved and converted to a storm sewer. Opponents to the latter part of the plan included the San Antonio Conservation Society and local architect Robert Hugman, who submitted a proposal in 1929 for a linear public park flanking the natural riverbed. In 1938 funds were appropriated for the construction of 2.5 miles of the River Walk, which was largely undertaken with labor provided by the Works Progress Administration. Today, the River Walk, now five miles long, is a pedestrian way sunken twenty feet below street level and comprising stone-paved walkways on either side of the river, rusticated stone retaining walls, picturesque arched bridges, boat landings, and staircases.

Located north of downtown San Antonio and completed in 2009, the Museum Reach is a 3.5-mile-long linear urban park that extends the River Walk to the Witte Museum, the San Antonio Zoo, Brackenridge Park, the Pearl District, and the San Antonio Museum of Art. Mission Reach, an additional eight-mile-long extension of the River Walk completed in 2013, connects to the four eighteenth-century Spanish Colonial missions (now designated a UNESCO World Heritage site) via hiking and biking trails. A celebrated icon of the city, the River Walk and its associated extensions are a reminder of the critical role that the river has played throughout San Antonio’s history.

HemisFair ’68 was the official title of the 1968 World’s Fair, held in San Antonio in commemoration of the 250th anniversary of the city. Architects O’Neil Ford and Allison Peery oversaw the exposition’s development, beginning in 1964. To make way for the grounds, the diverse Germantown neighborhood was razed, displacing 1,600 people, demolishing 1,349 structures, and altering or erasing two dozen streets. Established by the San Antonio City Council in 2009, the Hemisfair Park Area Redevelopment Corporation adopted a master plan in 2012 to revitalize the site as a mixed-use district with improved public spaces. The first phase, the play environment called Yanaguana Garden (located in the southwestern zone of the park), was designed by a team led by MIG, Inc., and completed in 2015. A team led by GGN Landscape Architects was selected in 2014 to design a Civic Park as part of the second phase, slated for completion in 2021.

In 2007 the City of San Antonio purchased a 311-acre parcel to establish a nature preserve and recreational park. Located approximately ten miles north of downtown and surrounded by dense suburban development, Phil Hardberger Park, once an agrarian landscape, is being developed under a master plan by Stephen Stimson Associates and D.I.R.T. Studio. Another example of renewal, Confluence Park is located on a former construction storage yard approximately two miles south of downtown. The three-acre park is situated along the Mission Reach segment of the River Walk on a bluff overlooking the San Antonio River and San Pedro Creek. Designed by Lake|Flato, Matsys Design, and Rialto Studio, the park officially opened in 2018.

These and other recent projects represent the prospect of successfully striking a balance between nature and culture, and between design and historic preservation. As San Antonio moves boldly into the 21st century, the high bar already set by Hemisfair, the Pearl District, the San Antonio Botanical Garden, and other designed landscapes is a strong indication that, well beyond its tricentennial, the city and its unique juxtaposition of old and new will continue to inspire visitors and residents alike, just as it did Olmsted in 1854:

We have no city, except, perhaps, New Orleans, that can vie, in point of the picturesque interest that attaches to odd and antiquated foreignness, with San Antonio. Its jumble of races, costumes, languages and buildings; its religious ruins, holding to an antiquity, for us, indistinct enough to breed an unaccustomed solemnity; its remote, isolated, outposted situation, and the vague conviction that it is the first of a new class of conquered cities into whose decaying streets our rattling life is to be infused, combine with the heroic touches in its history to enliven and satisfy your traveler's curiosity.