San Diego's Landscape Legacy

Early Colonization

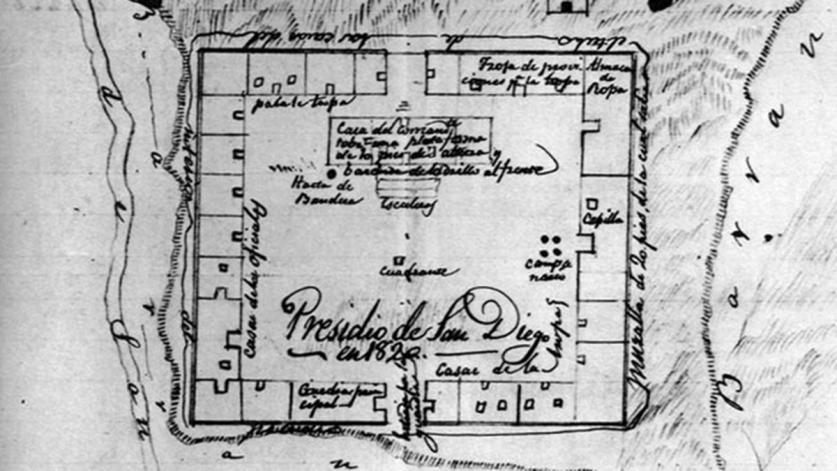

San Diego Bay was first claimed by Spanish explorers Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo and Sebastian Vizcaino in 1542 and 1606, respectively, the latter of whom named the region after the patron saint of the Roman Catholic Diocese of San Diego, San Diego de Alcalá. Threatened by encroaching Russian fur trappers, Spain began colonizing what was then the province of Las Californias in the mid-eighteenth century. In 1769 Spaniards led by Gaspar de Portola and Father Junipera Serra arrived from New Spain to establish the Fort Presidio of San Diego and the Mission Basilica San Diego de Alcalá on the western bluffs of the San Diego Valley. The Mission Basilica San Diego de Alcalá was the first in a chain of 21 missions built within California, including the Mission San Luis Rey De Francia in 1798, south of the San Luis Rey River. The missions were connected via the El Camino Real, a 600-mile-long road that stretched from the San Francisco Bay to the Mission Basilica San Diego de Alcalá, and whose markers can still be seen today. Supported by military garrisons, the missions were tools of conversion and conquest, as missionaries forced the indigenous Californians to live and work on settlements called reductions. The missionaries introduced western farming technology, supplanting the Kumeyaay’s seasonal agrarian pastures with large agricultural fields, whose produce were then traded to Boston, Lima and San Blas. The first major Colonial-era irrigation system used on the West Coast was the Old Mission Dam and aqueduct, now part of Mission Hills Regional Park, constructed by the Mission San Diego de Basilica San Diego de Alcalá in 1803. In 1804 Las Californias was split into the two provinces of Alta and Baja California, with San Diego forming aprt of the former.

San Diego as a Mexican Pueblo

After gaining independence from Spain in 1821, the Mexican government passed the Act for the Secularization of the Missions of California in 1833, resulting in the confiscation and sale of most of the missions’ extensive land holdings. Both the Mission San Diego de Basilica San Diego de Alcalá and the Mission San Luis Rey De Francia’s properties were divided and granted to prominent Mexican citizens. The disestablishment produced the Warner Carrillo Ranch in 1840, which in time became a notable way station along the Missouri Trail and is preserved as an historic site today, and Guajome Ranch in 1845, now Guajome Regional Park. Following Spain’s defeat, Fort Presidio was abandoned, and the soldiers formed a gridded community at the base of the hill, near the mouth of the San Diego River. In 1834 the Mexican Government recognized the community of San Diego as a pueblo, allowing the residents to form a municipal government and claim thousands of acres of surrounding land.

When the Mexican American War erupted in 1846, John C. Fremont, a major in the U.S. Army, seized San Diego’s town and harbor, where upon he raised the United States flag over the town’s Plaza de Las Armas. This occupation was short lived, however, and the town and its accompanying Fort Presidio, changed hands between the Americans and the native Spanish inhabitants, the “Californios,” several times during the Autumn of 1846. In December of that same year, American troops under the command of General Stephen Kearney engaged Colonel Andres’ Californios at the Indian village of San Pasqual, 30 miles north of San Diego. Following what is largely considered the bloodiest battle fought on California soil, commemorated today at the San Pasqual Battlefield State Historic Park, Kearney and Fremont conquered the Pueblo of Los Angeles. Their seizure of the city resulted in the signing of the Treaty of Cahuenga, effectively ending Californio resistance in the Alta California province. In 1848 Mexico surrendered to the United States, ceding its control of Alta California and New Mexico with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo. A year later the Mexican-United States Boundary Commission laid down the first boundary point on Imperial Beach, 24 miles southwest of San Diego, marked by a marble obelisk. The marker has been incorporated into the larger, binational Friendship Park, opened in 1971. Intended to symbolize cross-cultural communication and understanding, the park’s original message has been lost due to the site’s increased fortification following the September 11th terrorist attacks.

New Town and Horton’s Addition Established

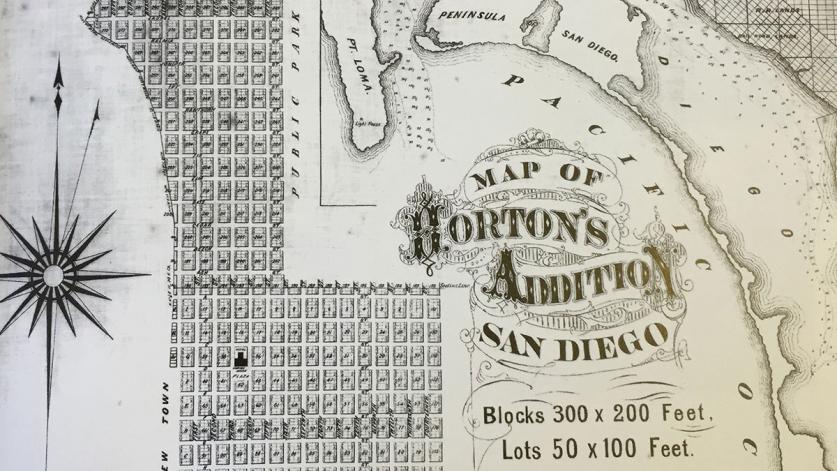

In 1849 Border Commission surveyor Lieutenant Andrew B. Gray suggested to trader William Heath Davis that a site closer to the San Diego Bay would be ideal for the formation of a new city. Shortly thereafter Davis partnered with four investors to buy 160 acres of pueblo land along the bay, where they built a harbor and laid down a street grid for their ‘New Town.’ Lacking access to fresh water, the new settlement, and the investment, floundered. Seventeen years after California’s admittance into the Union in 1857, American real estate developer Alonzo Erastus Horton bought 960 acres of pueblo land along the San Diego Bay, which included Davis’ New Town. Deemed attractive for its natural harbors, the settlement known as Horton’s Addition grew in population, supplanting the declining “Old Town” beneath Presidio Hill as the center of San Diego by 1880.

As the city continued to develop, civil and military institutions were formed. These included the city’s first public burial ground, Mount Hope Cemetery, founded in 1869, three miles beyond what were then the city’s boundaries, and the 1,400-acre City Park [today’s Balboa Park], established in 1868. Horton created a town plaza outside his hotel in 1870, which was deeded to the city in 1895. Initially designed by horticulturist Kate Sessions, the landscape that is today known as Horton Plaza Park was redesigned by Irving Gil in 1910, and Walker Macy in 2016. The city’s harbors were secured by the installation of Fort Rosecrans in 1873, along the peninsula of Point Loma, whose southern point had been reserved for military use in 1852. The fort’s burial ground, formed in 1879 and later expanded by the Works Progress Administration, was designated the Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery. During the interwar period civic leaders established a second public cemetery, the picturesque Greenwood Memorial Park designed by George Cook, adjacent to Mount Hope in 1907.

Late-Nineteenth and Early-Twentieth-Century Urban Development

The completion of the California Southern Railroad in 1885, which connected San Diego to the transcontinental Atlantic and Pacific Railroad, set off a land speculation boom that transformed the small town of San Diego into a bustling port city. As the population exploded from 5,000 to 35,000 between 1885 and 1888, a modern streetcar system was implemented to connect the downtown with growing neighborhoods on the outskirts of the city, reaching as far as Old Town San Diego. Among these new residential neighborhoods were the Gaslamp Quarter Historic District, developed from Davis’ New Town, established in 1850, and the coastal village La Jolla Park, formed by land speculators Frank Botsford and George Heald in 1886. Inspired by the City Beautiful movement, Botsford and Heald reserved five acres within their community for a waterfront park, designed in part by landscape architect Samuel Parsons, Jr. Known today as Ellen Browning Scripps Park, the blufftop site was at the forefront of a wider city beautification effort that would begin in earnest in the early twentieth century.

Despite an economic crash in 1889, growth continued at a steady pace throughout the 1890s and into the new century. The city became a tourist destination for thousands of health seekers who sought the advantage of the region’s tropical climate. Their presence spurred the development of spas and resorts, such as the Hotel Del Coronado, along the Bay. Meanwhile, suburban communities, including Golden Hill, Sherman Heights, and Banker’s Hill, continued to thrive farther away from the urban core.

At the turn of the century, civic leader George Marston, impressed by the beautification efforts undertaken in San Francisco and New York, pushed for an urban park system in San Diego. In 1899 he pressured the city council to reserve 364 acres of pueblo lands north of downtown San Diego as a public park. Designed by landscape architect Ralph Cornell and naturalist Guy Fleming in the 1920s, the reservation was expanded southward, eventually encompassing 1,750 acres. Acquired by the State of California in 1959, the park was renamed the Torrey Pines State Natural Reserve in 2007. In 1902 the San Diego Chamber of Commerce formed the Park Improvement Committee to develop City Park, which was constantly threatened by land speculators. Marston personally hired New York City landscape architect Samuel Parsons, Jr., who, with the assistance of local horticulturists Kate Sessions and T.S. Brandage, developed the 1902 Samuel Parsons & Company City Park Plan. Parson’s plan, carried out by George Cooke until 1906, transformed 300-acres of parkland into a picturesque landscape, complete with an ungraded, curvilinear circulation system that provided vehicular access, while also preserving viewsheds of the surrounding ocean, mountains and canyons. Assisted by Session, Parsons also implemented a planting palette of evergreen trees and exotic flora across large swaths of parkland, whose growth was supported by a series of reservoirs. An exception to this was the park’s system of canyons, which an admiring Parsons left relatively untouched. Parson’s landscape design would be altered only a few years later with the development of the 1915 Panama-California Exposition.

Desiring to boost both the population and economy of San Diego, G. Aubrey Davidson, President of the San Diego Chamber of Commerce proposed that the city host an exposition celebrating the opening of the Panama Canal in 1915. The Panama-California Exposition Company, founded in 1909, chose to host the event in City Park, renamed Balboa Park in 1910. The Company initially hired the Olmsted Brothers to design the exposition grounds, but the firm, who objected to the disruption of Parson’s design, soon dropped the project. Bertram Goodhue, taking over the design, laid out an axial plan surrounded by Spanish Colonial structures upon 167-acres of the parkland located atop the Vizcaino Mesa. Resulting from this design was the construction of the House of Hospitality and the International Harvester Building, later incorporated into the San Diego Zoo as the Reptile House. . A second master plan, designed by landscape architect John Nolen, was implemented in 1927, followed by the addition of the Alcazar Gardens, designed by architect by Richard Requa in 1935.

In 1907 Marston hired John Nolen to create a city plan for San Diego. Critical of the city’s existing grid of narrow, repetitive streets, he produced a plan that favored wide, planted boulevards, a European-style public plaza between today’s Cedar and Date Street, open recreational spaces along the bay front and a promenade to connect City Park to the plaza. Inspired by the City Beautiful Movement, Nolen also recommended that San Diego develop small, open spaces throughout the city with gardens, plazas, and playgrounds, as well as a system of parks for the mental and physical relief of residents. The city council was reluctant to adopt Nolan’s plan, and many of his suggestions went unrealized. However, Nolan’s 1908 proposal was influential in the design of the subsequent historic subdivisions of Mission, Marston, and Presidio Hills, all of which featured wide, curvilinear street patterns designed to follow the region’s natural topography. Additional elements of the 1908 city plan were realized in 1938, with the creation of the San Diego Civic Center, initially designed by landscape architect Roland Hoyt, and the Works Progress Administration, on infilled tidelands along the waterfront. In 1924 Marston again contracted Nolen to update the plan, which further recommended an eleven-mile-long, bay-front drive connecting the city’s south boundary to Point Loma, as well as the preservation of Old Town. Having been partially restored by sugar magnate John Dietrich Spreckels and architect Hazel Wood Waterman in 1909, Old Town was designated a state park in 1968.

Despite the council’s refusal to adopt the Nolen plan in its entirety, Marston continued to press for the creation of civic and recreational spaces. In 1907 he and members of the city’s Chamber of Commerce restored the Casa de Carrillo, the oldest surviving adobe home in San Diego, built in 1817, and converted the surrounding landscape into the Presidio Hills Golf Course. Marston purchased the nearby Presidio Hill, the site of the old Spanish Fort, that same year. John Nolen created a plan to convert the steep site into Presidio Park, accepting design advice and refinements from fellow landscape architect Roland Hoyt, horticulturalist Kate Sessions, and Percy Broell, who later served as the park superintendent. Marston further underwrote the building of the park’s Spanish Revival-style Junipero Serra Museum, designed by William Templeton Johnson in 1928. Patronage was and continues to be an essential ingredient in the formation of various public spaces across the city. Operating concurrently with Marston, fellow philanthropist Ellen Browning Scripps underwrote the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, (1905), the adjacent the Torrey Pines State Reserve (1921), and the Children’s Pool in La Jolla (1931).

During the early 1900s, San Diego’s city leaders acquired federal assistance to improve the harbor for commercial shipping, with funds coming from the sale of large tracts of waterfront property for use as naval installations. One of these sites included the Naval Training Center, placed along the shores of Point Loma in 1921. Initially sited on 200 acres, the base was expanded with the dredging of the adjacent harbor in 1939. The onset of World War II resulted in the creation of Camp Callan, adjacent to the Torrey Pines Reserve, in 1941 and Camp Pendleton on the former Rancho Santa Margarita y Las Flores, in 1942. The Naval Training Center remained active throughout the Cold War before being decommissioned in 1990, when the land was transferred to the city and subsequently developed into the mixed-use neighborhood Liberty Station and the Naval Training Center Park. Camp Callan, closed in 1945, was similarly transferred back to the city, and subdivided for educational and recreational institutions including the University of California, San Diego (1956), Torrey Pines Golf Course (1957), and Salk Institute of Biological Studies (1967).

Mid to Late Twentieth Century and Beyond

In the postwar years, increased suburban growth within Mission Valley, and the introduction of the highway system, shifted commercial and institutional development, such as the University of California, San Diego (1956), away from the city’s center to its periphery. As the region expanded, landscape architects played an increasingly important role in high-profile, public projects. Beginning in the 1960s, Garrett Eckbo created overarching design principles for the entirety of Mission Bay Park, encouraging a variety of uses while unifying the experience by maximizing waterfront access and orienting visitors towards the shoreline. Meanwhile, local firm Wimmer Yamada & Associates created plans for SeaWorld San Diego (1964) and Embarcadero Marina Parks, North and South (1978). Despite a rising population and the introduction of popular recreational spaces, the once bustling downtown San Diego entered a state of decline. In 1972 San Diego Mayor Peter Wilson announced plans to reduce urban blight by introducing mixed- use housing, educational, recreational, and cultural amenities to the downtown. In response, the Marston Family, continuing their legacy of patronage, sponsored a study by prominent urban planners Kevin Lynch and David Applewood. Called Temporary Paradise?, the study advocated for the creation of sharable cultural spaces that would democratize the city’s urban core.

Afterwards, in 1975 the city formed the Centre City Development Corporation (CCDC), a public, non-profit organization. The CCDC issued a master plan created by ROMA Design Group, which laid the foundation for urban renewal and resulted in the revitalization of historic landscapes and districts, such as the Gaslamp Quarter, and the creation of Modernist and Postmodernist urban spaces. The six-block-long Horton Plaza mall, by architect Jon Jerde, with a landscape design by Wimmer Yamada & Associates, opened in 1985. While successful in bringing businesses and visitors into downtown areas, renewal projects also sometimes resulted in the displacement of existing residents. In more recent decades the city has turned its view towards the water, transforming former industrial sites into public spaces that include Children's Park and Pond (1995), Martin Luther King, Jr. Promenade (1997), Tuna Harbor Park (2012), and San Diego Civic Center’s Waterfront Park in 2014.