Richmond's Landscape Legacy

The What’s Out There Cultural Landscapes Guide to Richmond is the fourth in an ongoing series of guides being produced in a collaboration between The Cultural Landscape Foundation (TCLF) and the National Park Service (NPS). The series launched in March of 2016 with a guide to Philadelphia, followed later that year by one to New York City. The Boston guide was published in 2017, and the final guide, to Baltimore, will be released by the end of 2018.

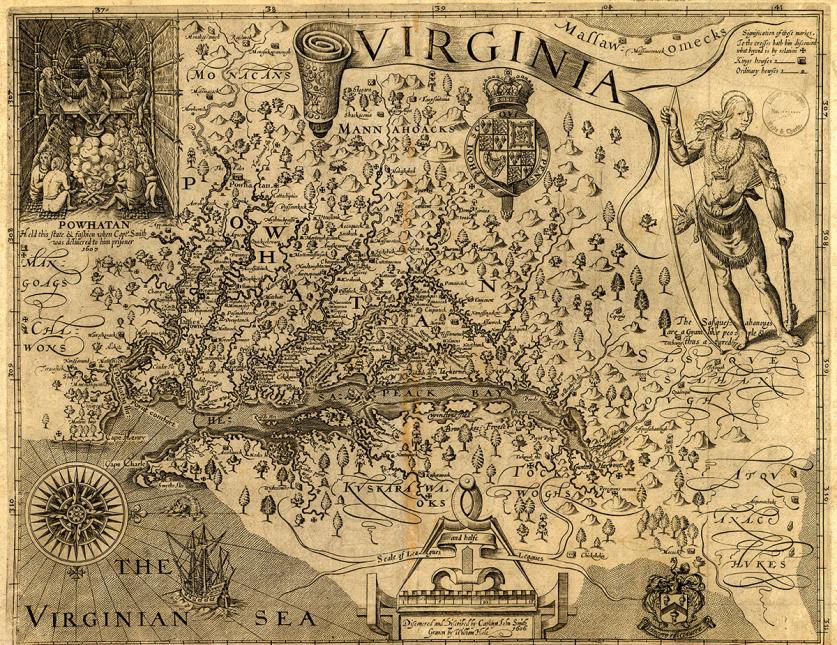

Prior to English settlement of the Colony of Virginia in the early 1600s, the region that would become Richmond was home to the Native American tribes of the Powhatan Confederacy. Spurred by royal charter from James I, John Newport led the first colonists to this hilly, wooded landscape along the banks of a river, which they dubbed the James in honor of their king, in 1607. Although Newport’s expedition reached the site of modern-day Richmond, the colonists ultimately turned back to found Jamestown downriver. An encampment was established at the upriver site two years later, when explorer John Smith famously proclaimed that there was “no place so strong, so pleasant, and delightful in Virginia, for which we called it None-such.” Several decades of conflict between the Powhatans and the English followed, and it was not until 1673 that William Byrd I was granted land for a permanent settlement at the falls of the river, near Smith’s original camp, on a portion of the site that would become Richmond.

The meandering James River has been a determining feature of Richmond’s cultural landscapes since the city’s inception. Unable to maneuver their ships farther upriver, the colonists were forced to settle along the Fall Line, where hard bedrock gives way to the soft sediments of Virginia’s coastal plain. What was at first a limitation proved advantageous as the area was well-suited to host a port; its varying topography provided natural defense; and, later, the rapid, falling waters were essential to the growth of industry (water-powered mills, for example).

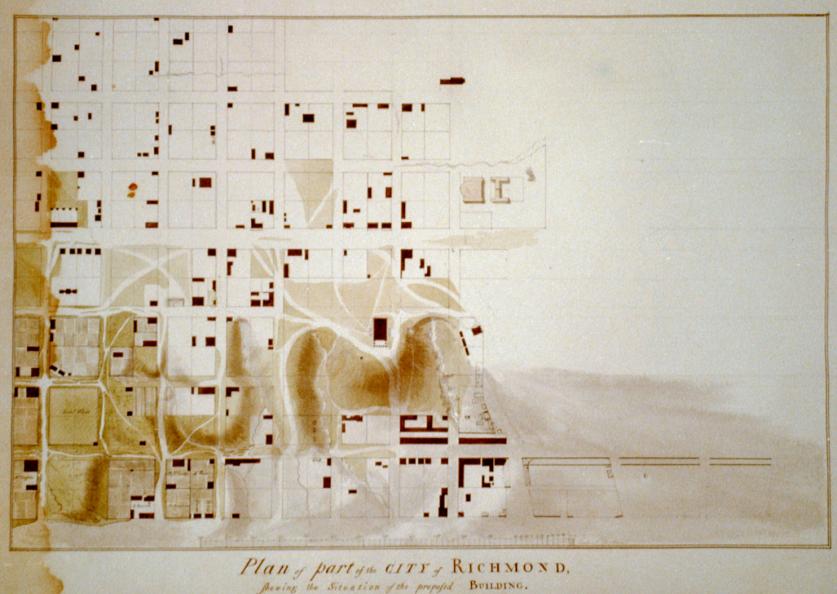

In 1733 William Byrd II (son of William Byrd I) founded the Town of Richmond. Four years later, Major William Mayo laid out a grid of 32 streets in present-day Church Hill, a high point overlooking the river on its north bank. Richmond was officially incorporated by 1742. Meanwhile, a new settlement was developing on the south side of the river—Rocky Ridge (later called Manchester), which would not benefit from a formal plan until 1769 (by Byrd II’s son, William Byrd III). Remnants of this plan are still discernible in the Manchester Residential and Commercial Historic District, listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1998.

Unlike other planned colonial cities, such as Philadelphia or Savannah, public space in the form of squares or greens was not included in Richmond’s original design. Rather, town commons were relegated to the outskirts of the street grid, primarily along the riverfront. This decision would profoundly impact the siting and development of nineteenth-century public parks.

In its early years, Richmond was a small town, yet its connection to the tobacco industry and proximity to the river helped solidify its role as a critical port and commercial center. The rich soil of the region fueled the growth of expansive plantations, primarily for the sourcing of tobacco, and by the turn of the eighteenth century the Byrd family had established several tobacco warehouses. The burgeoning tobacco industry was boosted by the expansion of the roadway system to reach Williamsburg, the well-established city located approximately 50 miles southeast of Richmond. By the second half of the eighteenth century, at least one-sixth of all of the colonies’ tobacco crops were passing through Richmond for shipment across the Atlantic. Local commerce was also thriving, and the open-air market at 17th and Main Streets, still in operation today, was created at this time. While few significant structures of the period remain, one extant example is the Old Stone House (now the Edgar Allen Poe Museum), constructed circa 1740 and saved from demolition in 1911 by the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities.

In 1779 Virginia’s seat of government moved from Williamsburg to Richmond, the latter believed to be more defensible. Then-Governor Thomas Jefferson chose a gently sloping knoll atop Shockoe Hill as the site of his Classical Capitol building, evoking the Athenian Acropolis, and secured twelve acres of the surrounding land for its grounds. The landscape was dedicated as the "Public Square" by 1798, and the City of Richmond assumed ownership in 1804. An 1816 plan by Maximillian Godefroy incorporated walkways, terraces, fountains and plantings, and in 1851 John Notman implemented a naturalistic plan with meandering walks and a planting scheme of native trees.

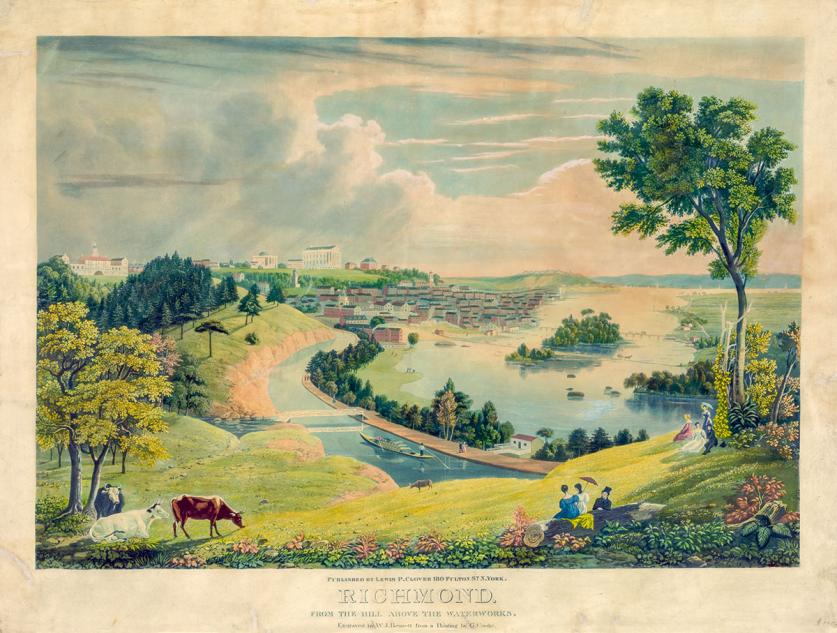

Jefferson’s siting of the Capitol on a hill took full advantage of the topography, a strategy that was frequently implemented for other important buildings and landscapes in the years that followed. One example is Hollywood Cemetery, also designed by Notman, an expansive rural cemetery developed for the interment of Richmond’s elite at Harvie’s Wood, another high point overlooking the James.

In 1785 George Washington proposed plans for the James River and Kanawha Canal, significantly impacting the development of the city. The canal provided a means to bypass the falls, thus enabling ships to reach Richmond from upriver. Industrial facilities, including quarries and mills, were established along the river, and Shockoe Slip was constructed as a means of access between the city and canal. One such industrial complex was Tredegar Iron Works, established in 1837 to produce iron and ammunition, which would prove to be an asset during the Civil War.

Most residential properties in antebellum Richmond were vernacular detached houses placed on large lots with outbuildings. Many are still standing today in neighborhoods such as the Jackson Ward, St. John’s Church, and Shockoe Valley and Tobacco Row Historic Districts. In the more densely populated areas of Richmond, attached housing began to develop—Carrington Row in St. John’s Church Historic District, designed circa 1810, is one of the earliest and most prominent examples.

Richmond’s population increased tenfold from the 1780s to the turn of the nineteenth century, with nearly 6,000 residents by 1800. This number would grow to 38,000 by 1860, making Richmond one of the largest cities in the South at the outbreak of the Civil War. This rapid population increase led to significant density in residential neighborhoods, which, along with the loss of green space along the river, prompted the need to establish dedicated public open space. The City of Richmond thus acquired land for three public squares in 1851: Gambles Hill, Western Square (now Monroe Park), and Eastern Square (now Libby Hill Park), the latter two of which are listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

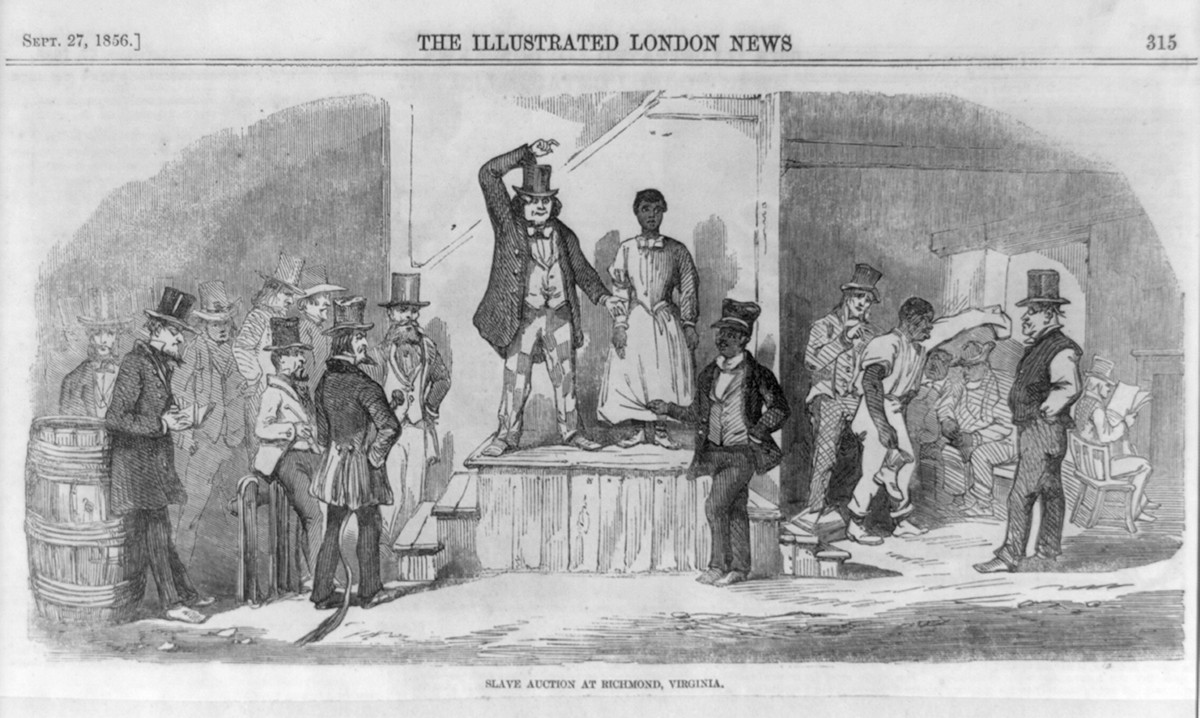

In 1808 Congress enacted a law prohibiting the importation of enslaved peoples to the United States, resulting in the rise of the domestic slave trade. By 1840 Richmond was the largest slave-trading center in the Upper South (second to New Orleans in the South overall). Shockoe Bottom served as the center of the city’s slave trade, hosting numerous auction houses, offices, hotels for traders, and holding facilities, known as “slave jails.”

Virginia seceded from the Union on April 17, 1861, and on May 8, Richmond became the new Capital of the Confederacy (replacing Montgomery, Alabama). A Classical Revival mansion, constructed in 1818 several blocks from the Virginia State Capitol, was selected to be the executive mansion (now known as the White House of the Confederacy) for Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederacy from 1861 to 1865.

The landscapes of the greater Richmond area were irrevocably shaped by the war. Many battles were waged in the region, and the Richmond National Battlefield Park, established in 1932, preserves thirteen of the most significant sites, commemorating the Seven Days Battles of 1862, the Overland Campaign of 1864, and the Richmond-Petersburg Campaign of 1864-65. Located near strategic geographic features, including rivers and bluffs, these landscapes highlight the critical role that topography and infrastructure played in determining battle strategies and outcomes. Malvern Hill, for example, exhibits the strategic advantage Union forces gained as they positioned themselves between the hill’s slopes and the adjacent lowland swamps.

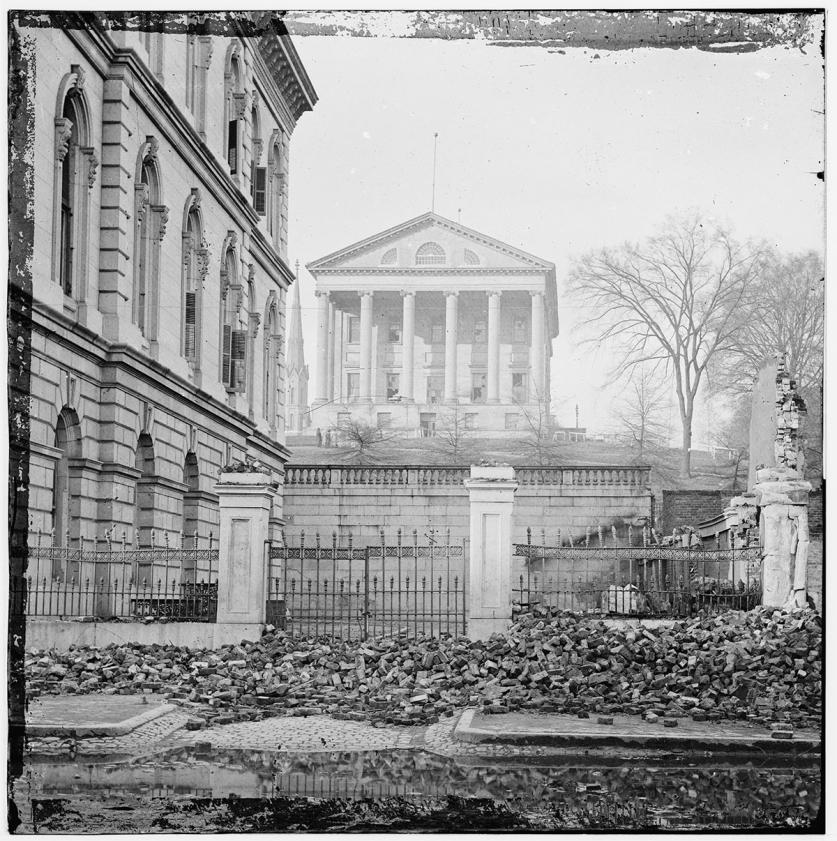

As an industrial center, the city was poised to supply not only ammunition, but tents, uniforms, and other necessary goods to the military. Many of the city’s public spaces became wartime utilities, including Chimborazo Hill, the site of a major military hospital from 1861 (now a public park), and Belle Isle, which was used as a Union prison camp. In 1865 a devastating fire consumed much of Richmond’s core as the Confederate army evacuated the city. While the city rapidly rebuilt, myriad original buildings and landscape features were lost.

Jackson Ward, a north Richmond neighborhood established in 1793 by emancipated slaves, was the destination for many of the African Americans who relocated to Richmond from throughout the South during Reconstruction. In the latter half of the nineteenth century, the area became a hub for prominent African American business owners and entrepreneurs, including Maggie Lena Walker, the first African American female president of a bank in the United States (her home is now a National Historic Site). Today, Jackson Ward is one of the most historically intact neighborhoods in Richmond.

Hired as Richmond city engineer in 1873, Wilfred Cutshaw was key in developing and rejuvenating many public parks at the end of the period of Reconstruction, including Byrd Park, Chimborazo Park, and two of the public squares set aside by the government in 1851, Libby Hill and Monroe. Cutshaw’s work was a sign of progress to come.

The first successful electric streetcar system in the United States was established in Richmond in 1887, designed by Philadelphia engineer Frank Sprague. This gave rise to some of the first streetcar suburbs, many of which are historic districts today, including Ginter Park and Frederick Douglas Court. Belle Isle, left empty after it ceased to house Union prisoners, became the site of a hydroelectric plant to power the streetcars on the south side of the river, including a trolley line that led to Forest Hill Park.

During this period the prominent boulevard, Monument Avenue, was developed. The earliest design of the avenue, attributed to civil engineer C.P.E. Burgwyn in 1888, proposed the extension of Franklin Street through a meadow west of downtown. Two years later sculptor Jean Antoine Mercie’s towering statue of General Robert E. Lee was sited within a 200-foot-diameter traffic circle. The boulevard was gradually extended one block to the east and thirteen blocks to the west as new structures, monuments, and plantings were added, including a monument dedicated in 1996 to Arthur Ashe, a Richmond-born tennis champion and African American civil rights leader. As part of a national reckoning with Confederate-associated monuments, five of the six memorials were removed from the avenue’s one-and-a-half-mile length between 2020 and 2021.

Several key people and firms shaped Richmond’s landscapes in the twentieth century. Charles Gillette, a young landscape architect who worked for Warren Manning and relocated to the Commonwealth in 1913 to develop Manning’s plans for Richmond College (now the University of Richmond) designed several Colonial Revival gardens. In 1927 Gillette was commissioned to develop the grounds for Virginia House, an English mansion located in the 444-acre garden suburb of Windsor Farms, which was laid out by planner and landscape architect John Nolen. Over the course of twenty years, Gillette worked closely with the owners to create a Tudor-style garden that complemented the sprawling mansion on a dramatically sloped one-acre lot. Expanded to nine acres in 1939, the property lies adjacent to another imported English manor with a landscape designed by Gillette, the 23-acre Agecroft Hall. On both properties Gillette’s garden terraces accommodate the steeply pitched topography extending to the James River. Gillette also designed a two-tiered Colonial Revival memorial garden at Tuckahoe Plantation, Thomas Jefferson’s boyhood home, on a bluff several miles west of the city.

Richmond is also the setting for several significant Modernist landscapes designed by Gillette and others, including the Altria Headquarters (formerly Reynolds Metals Company International Headquarters). A decade before his passing in 1969, Gillette collaborated with architect Gordon Bunschaft to develop the 121-acre campus with a long reflecting pool, allées of willow oaks, and a courtyard housing fountains and a specimen magnolia. Shortly thereafter, Zion & Breen Associates designed the three-acre Kanawha Plaza, a distinctly Modernist public space with a stepped fountain rising from a sunken pool. By the end of the 1970s, Danadjieva and Koenig Associates had developed their conceptual design for the 550-acre James River Park System, which includes Modernist insertions at Belle Isle and the Postmodernist reinterpretation of Tredegar Iron Works.

In recent decades there have been efforts to address and interpret those histories associated with the city’s African American heritage. In 1998 the Richmond City Council Slave Trail Commission was established to lead this effort, engaging a team of archeologists to investigate Lumpkin’s Slave Jail, among Richmond’s largest and most notorious “slave jails,” which is now commemorated along the city’s 2.5-mile pedestrian route.

A rebirth has also taken hold at Richmond’s many African American cemeteries and burial grounds, long desecrated and neglected, which are receiving renewed recognition and commemoration from the efforts of dedicated local non-profit groups. Two such cultural landscapes, Barton Heights Cemeteries and Shockoe Hill African Burying Ground, were listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2002 and 2022 respectively illustrating their historic significance.

As evidenced by the city’s vast and unique cultural landscapes, and its ability to accommodate changes in style and taste over time (from Colonial Revival to Modernist and Postmodernist works), the capital of the Commonwealth continues to preserve, protect and interpret its natural and cultural heritage while continuing to move forward.