Plaquemine Point Faces Imminent Threat

Plaquemine Point, a peninsula in a bend of the Mississippi River some eight miles south of Baton Rouge, LA, contains a nationally significant old growth forest that could be partially destroyed as the result of a proposed bridge and road project. This half-wooded, half-cleared oblong site approximately ten miles long and one mile wide in Sunshine, LA, is a significant cultural landscape; it is part of the ancestral home of a number of indigenous tribes, including the Chitimacha, Houma, and Bayou Goula, who inhabited the land for thousands of years, and also represents more than 300 years of Western settlement. The area was colonized by the French and Spanish and provided refuge for a group of Acadian exiles in the eighteenth century – several of whose descendants still reside there. In the middle of the peninsula is the 60-acre A.E. LeBlanc Forest Natural Area, an old-growth forest including trees between 220 and 360 years old. It is the only privately-owned old-growth forest in Louisiana included in the Old-Growth Forest Network (OGFN), a national non-profit established in 2011 focused on protecting native, mature forests, that includes more than 200 sites in 35 states. According to the OGFN, “only a fraction of [one percent] of Eastern original forests, on average, remain standing." The Louisiana Department of Transportation and Development (LADOTD) is examining three potential routes for the bridge and road project, one of which would traverse Plaquemine Point longitudinally, directly impacting more than 150 acres of forest and potential archaeological sites that could reveal the rich history of settlement in the region. A previously identified archaeological site on the peninsula located near the proposed route is an abandoned African American cemetery with one remaining gravestone, that of an African American Civil War veteran. If this bridge and road alternative were to be selected, it could be in violation of state laws protecting old growth forests and Governor John Bel Edwards’ Climate Action Plan, which calls for the retention of old growth forests.

History

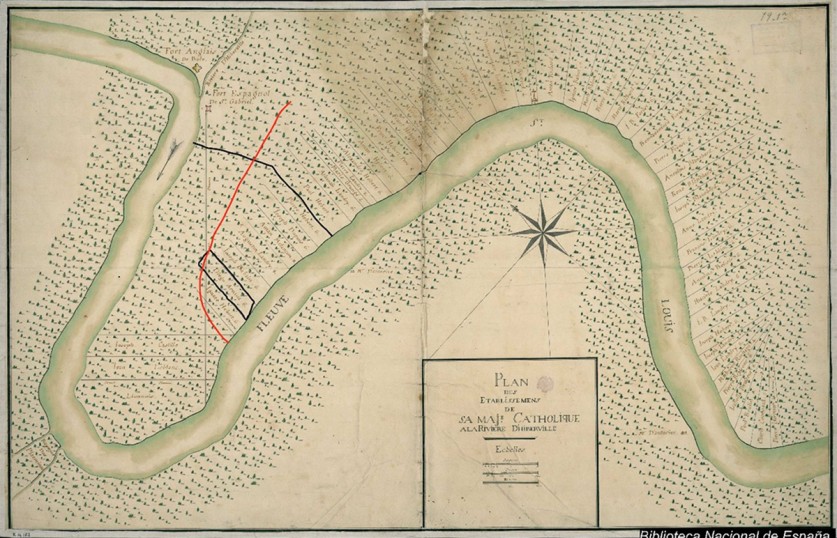

Plaquemine Point is part of Iberville Parish, on the east side of the Mississippi River, near the Baton Rouge metropolitan area. Historically, it was known as Riviere D’Hiberville or Manchac Point (French) or as Costa de Ybervile (Spanish). In 1767 the peninsula was a Spanish outpost, important militarily for the protection of navigation in and out of New Orleans. Spain had acquired Louisiana from France in 1762 and England had acquired the area north of Bayou Manchac (including Baton Rouge) in 1763; the Spanish built Fort San Gabriel on the south side of the bayou on the peninsula, across from the English Fort Bute, with the bayou the international border between the Spanish and British territories.

In 1767 a group of approximately 200 Acadians arriving in New Orleans who had been exiled from Acadia (today’s Nova Scotia) by the British in 1755, and who had spent more than a decade, unwelcomed, in Maryland, were invited by the Spanish governor to settle at Fort San Gabriel. The Acadian presence would help fortify the area against the British. Spanish land grants were distributed to the Acadians; they were told to immediately build cabins on the lands assigned to them, and to construct shed-like structures in the vicinity of the fort in the early days before their cabins were complete. A road divided the point longitudinally, with twelve yards between the properties. A Spanish Commandant’s letters written during 1767-1770 offer valuable insights into the life of the Acadians and Native American people in the area during this time; most have yet to be translated from Spanish to English.

A little under a decade after the Acadians’ arrival, in 1775, the Revolutionary War began. In 1779, Spain declared war against England and aided the Americans in their fight, crucially protecting New Orleans and the Mississippi River delta from the British. General (and Governor at the time) Bernardo de Gálvez and his army of Spanish soldiers, along with Acadians and Atakapa-Ishak Indians, hiked through the Plaquemine Point area to capture Fort Bute. The eighteenth (and nineteenth) century also saw the increase of enslaved Africans and African Americans on plantations and elsewhere, which added another layer of culture and history. Two plantations, the Bagatelle and Lucky Plantations – located on the northern and southern edges of the peninsula – are listed in the National Register of Historic Places and the latter is located very near the point at which the proposed bridge and road would cross into Plaquemine Point.

Remarkably, due to private ownership, the landscape of Plaquemine Point has been preserved over the centuries. (About 99% of the peninsula is privately owned.) In the middle of the point is the 60-acre A.E. LeBlanc Forest Natural Area, a nationally-significant old-growth cypress included in the Old-Growth Forest Network, a national non-profit established in 2011 focused on protecting native, mature forests, that includes more than 200 sites in 35 states. It is named after Alphonso Etienne LeBlanc, Sr., the grandfather of the eldest living LeBlanc landowners on the Point, and a descendant of Acadian settlers. The site is also registered with the Wildlife Diversity Division of Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries and the Louisiana Purchase Cypress Legacy Organization. Within the forest are many old-growth cypress trees between 220 and 360 years old, some registered as Legacy Trees, or trees (based on core samples taken from their trunks) that were alive at the time of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. Sixteen landowners, after learning the age of the cypress trees on their property, wanted to see the forest preserved long-term and pursued its designation on the Louisiana Registry of Natural Areas, a recognition bestowed by the state’s Department of Wildlife and Fisheries and by the Governor of Louisiana in 2022. Adjacent properties also have old-growth cypresses, and several neighborhood tracts are being used for Wetland Mitigation Credits in a Wetland Banking arrangement with the state – meaning that projects that negatively impact wetlands in one part of the state can be mitigated by creating or expanding wetlands elsewhere to offset the net loss. Some of the land on Plaquemine Point has been set aside and preserved in perpetuity so that other projects elsewhere could be built. Around the entire point is forested land that offers a continuous habitat for wildlife, including bald eagles, woodcock, turkeys, bobcats, gray and fox squirrels, hundreds of bird species, barred and great horned owls, and white-tail deer. With the animals’ nearby habitats decreasing, Plaquemine Point serves essentially as a wildlife refuge.

Threat

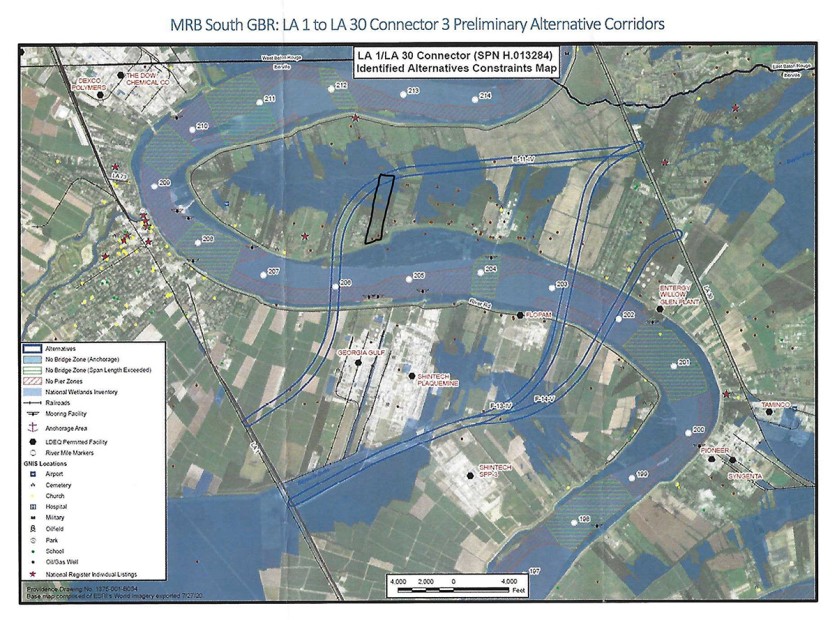

The Louisiana Department of Transportation and Development (LADOTD), in cooperation with the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), is planning a roadway and Mississippi River Bridge that would connect Louisiana Highway One (LA 1) to Louisiana Highway 30 (LA 30) via a controlled access, four-lane divided roadway. The bridge would span the Mississippi River, with travel lanes twelve feet wide and outside shoulders eight feet wide. Capital Area Road and Bridge District (CARB-D) was statutorily created “for the purpose and mission of planning, financing, and building a Mississippi River crossing and connectors,” with a commission comprised of representatives from five parishes, a governor’s appointee, and a representative from LADOTD. CARB-D hired Atlas Technical Consultants to carry out the environmental planning and review process, which began in July 2020.

In April 2022 a few residents of Plaquemine Point read an announcement of a public meeting in the local newspaper and heard about it on the local television news stations. During this meeting the public was informed that ten routes (down from 32) were being considered and would be narrowed down to three after a period of public comment. Three days before the public comment period was closed, the Iberville Parish president was quoted in a local newspaper, the Plaquemine Post South, stating: “The consultants know where the final three [alternatives] are…” On May 27, three final options were announced for the Mississippi River Bridge Project, all three located in Iberville Parish, with connections on the west side of the river south of Plaquemine, and on the east side of the river in St. Gabriel.

Alternative E-11-IV would cut through Plaquemine Point longitudinally, destroying the habitat in the middle of the peninsula, as well as the pathway of the road that the Spanish used to divide the land grants given to Acadian settlers in 1767. The land that this road traversed has never been archaeologically studied; doing so could yield important information about the history of settlement at the fort. E-11-IV would also pass very near Fort San Gabriel on the peninsula and the site where the Acadians built their shed-like structures when they first arrived. Many of the residents of Plaquemine Point are descendants of the original Acadian settlers; E-11-IV has the potential to wipe out an important part of their cultural legacy. Further archaeological investigation is also merited at the site of an African American cemetery and church where one grave marker and several depressions in the ground indicating unmarked graves were discovered in the late 1980s. This site could reveal previously unknown information about the history of African American life and culture in the area.

Significantly, based on a calculation of a 600 foot-wide path (used by Atlas in analyzing each potential route), the proposed bridge and roadway could destroy more than 150 acres of forest, approximately half of the area containing old growth forest, and potentially violating Louisiana law RS 3:4278.5, which expressly prohibits the cutting of cypress trees, stating, “it shall be unlawful for any person or government entity, or his agent or employee, to cut, fell, destroy, remove, or to divert for sale or use, any cypress trees growing or lying on public land owned by or under the control of the state of Louisiana or local governing authority.” LADOTD’s plan would further interfere with properties participating in the Ellison Wetland Mitigation Credits Program, which set aside wetlands in perpetuity, and would also undercut Governor John Bel Edwards’ 2022 Climate Action Plan, which promotes the critical importance of old-growth forests.

Thus far there has been minimal active outreach from LADOTD to the Plaquemine Point community; the public have to regularly search the CARB-D website and scour local news outlets to stay informed about public meetings and other updates. Most of the previous stakeholder engagement has been with large industrial companies on the other side of the Mississippi River. The first time LADOTD directly contacted members of the Plaquemine Point community was in late August 2023, when they requested access for their representatives to several properties to conduct studies on the final alternatives.

When federal funds are involved, as is the case with this project, a National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) review process must be undertaken, which results in an Environmental Assessment (EA) or Environmental Impact Statement (EIS), before the project can proceed. An EA is much shorter than an EIS and involves cases when an agency is unclear about whether a proposed action will have significant environmental or cultural effects. An EIS is undertaken when it is clear that a project will significantly affect natural and cultural resources; regulatory requirements for an EIS are more detailed and rigorous than for an EA, and the process can take up to two years. During a September 2023 public meeting an Atlas representative (the project’s manager) stated that they are working under the assumption that they will be proceeding with an EA, and that Atlas anticipates being done with the entire environmental planning process, with a “signed environmental document” ready, no later than winter 2024 – a timeline incompatible with an EIS. Presuming that no EIS will be necessary, especially when old-growth forests, wetlands, and potential archaeological sites are present, would appear to be a premature and troubling assumption. It is clear from the recorded and publicly accessible meeting that LADOTD and Atlas are under pressure to remain within a strict timeline and that they are unwilling to entertain extending it past 2024.

Thus far the State Historic Preservation Office has not been consulted on the project, nor has a review pursuant to Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act, which considers potential effects to historic properties and cultural resources for projects that involve federal funds, been initiated.

How Can You Help

Tell decision makers to abandon the bridge and road alternative known as E-11-IV (as part of the MRB South GBR: LA 1 to LA 30 Project), which would damage a rare old growth forest. Please contact each of the following:

Governor John Bel Edwards

Office of the Governor

PO Box 94004

Baton Rouge, LA, 70804

https://gov.louisiana.gov/index.cfm/form/home/4

Mr. J. Mitchell Ourso, Jr.

Iberville Parish President

P.O. Box 389

Plaquemine, LA, 70765-0389

esongy@ibervilleparish.com

Mr. Jerry Pitts

Federal Highway Administration, Louisiana Division

5304 Flanders Drive, Suite A

Baton Rouge, LA, 70808

jerry.pitts@dot.gov

Ms. Nicole Hobson-Morris, Louisiana Division of Historic Preservation

P.O. Box 44247

Baton Rouge, LA, 70804

nmorris@crt.la.gov

Noel Ardoin, Environmental Administrator, LADOTD

1201 Capitol Access Road

Baton Rouge, LA, 70802

noel.ardoin@la.gov

Atlas Technical Consultants

c/o Kara Moree

8440 Jefferson Hwy, Suite 400

Baton Rouge, LA, 70809

https://www.oneatlas.com/contact-us/

A Friends of Plaquemine Point website is being developed that will have more detailed information about the cultural landscape and how to support the community. TCLF will share the link in a future update.