Rehabilitating Postwar Plazas: A Primer

It has been said that time is change. If change is inevitable, then the best approach to treating cultural and historical resources is one that seeks to manage change through sound stewardship in an effort to achieve an appropriate balance rather than an impossible stasis. Achieving that balance is perhaps the most important part of any rehabilitation project. And, in fact, the rehabilitation of an historic designed landscape has the potential to offer more value than a do novo design because successfully rehabilitated landscapes retain their accrued cultural value in addition to providing the benefits of present and future use.

At the recent ASLA Conference on Landscape Architecture in San Diego, TCLF’s Charles Birnbaum, FASLA, FAAR, was joined by Susan Rademacher, Hon. ASLA, parks curator at the Pittsburgh Parks Conservancy, and Ken Smith, FASLA, principal at Ken Smith Workshop, to put forth a practical framework for rehabilitating postwar plazas. The following is based upon that panel discussion.

Plazas differ in their carrying capacity for change. Understanding historical context and integrity is key to determining an appropriate treatment.

As the presentations made clear, fully understanding the context of a postwar plaza, as with any discrete site, involves establishing its historical significance and its level of integrity. That critical context will determine the plaza’s carrying capacity for change, which is then balanced against contemporary needs and desires. The latter are often best discovered through public engagement and may involve consideration of accessibility, safety, ease of maintenance, environmental sustainability, future stewardship (e.g., via public-private partnerships), and future uses.

Union Bank Plaza (1968), in Los Angeles, is an exemplary design by Garrett Eckbo that retains a high level of integrity and remains in good condition.

Managing Change: A Certain Way of Thinking

When rehabilitating any designed landscape, it is helpful to begin by thinking in the terms and parlance of historic preservation. Such an approach recognizes that it is a plaza’s historical and physical contexts—two separate factors—that together determine its significance and, therefore, the appropriate type and level of intervention. Historical context refers to the historical patterns or trends through which an historic designed landscape is understood, and its meaning is formed. Is the plaza a strong example of the Modernist style? Is it a rare extant work by a noted designer? Is it an exemplar of that designer’s work or philosophy? Is it a progenitor of a certain typology (e.g., a Park-Plaza hybrid)? Answering these questions and many others helps to establish the site’s historical significance, and finding the answers most often involves rigorous research and analysis.

Created by M. Paul Friedberg + Partners in 1975 and rehabilitated in 2019, Minneapolis’ Peavey Plaza retained a high level of design integrity despite being in a dminished state. - Photo © Elizabeth Felicella, 2019

When considering a site’s physical context, one should assess its integrity, which, strictly defined, is its ability to convey its significance. Note, however, that a site’s integrity is not the same as its physical condition. The latter refers to the state of its appearance or function. But according to the guidelines of the National Register of Historic Places, integrity is defined by seven separate aspects that do not depend solely on appearance or function. Thus, a poorly maintained plaza may yet retain considerable integrity. In terms of designed landscapes, one might think of the dichotomy between condition and integrity as the difference between structural and cosmetic states. Note, too, that several aspects of integrity are interrelated and that, as with understanding historical context, discerning them will rely on research and documentation.

Applying the Seven Aspects of Integrity:

- Location: Location is the place where the historic property was originally constructed. For works of landscape architecture, it is highly unlikely that the location will have changed, so postwar plazas, generally speaking, will retain their integrity of location. Note, however, that Location is not the same as Setting (see below), although the two are related.

- Design: Design refers to the combination of elements that together express the form, plan, space, structure, and style of the plaza while also creating its overarching visual and spatial relationships. These elements in turn are derived from and express a particular use of proportion, scale, technology, ornamentation, materials, etc. Note that, importantly, these components derive from conscious decisions made when the plaza was originally conceived, planned, and built, which gives rise to the important notion of design intent—the way in which the designer intended the plaza to be experienced and understood.

- Setting: Setting refers to the physical environment of the plaza—the character of the place, not just its geographic coordinates. Assessing the integrity of the setting therefore involves assessing the plaza’s relationship to its surroundings.

- Materials: Materials are the physical elements used to create the plaza. These may convey preferences related to the design, but they may also convey historical conditions related to state of technology and the availability of resources.

- Workmanship: Workmanship generally refers to the physical presence of craft, skill, or artisanship that remains discernable in the plaza’s design and construction, either in the property overall or in its individual components.

- Feeling: Feeling refers to the plaza’s expression of the aesthetic or historic sense of a particular time. Although feeling results from the presence or absence of certain physical features, it also depends upon subjective, individual perceptions that, taken together, help to convey the property's historic character.

- Association: Association is the direct link between the plaza and some important historical event or person.

The setting of 140 Broadway is key to its significance. The 80-foot-wide, open plaza was designed as an expansive travertine plinth for Isamu Noguchi’s Red Cube (1968) amid a dense urban environment. - Photo by Charles A. Birnbaum, 2018

It is important to remember that the historical and cultural significance of plazas and other designed landscapes can also derive from the way they have been adapted after they were originally built, thus illustrating the changing preferences, attitudes, and uses over a given period of time. These and other points were further fleshed out and illustrated by four case studies.

Plantings at the David M. Lilly Plaza (left), designed by Oehme, van Sweden & Associates, and a spray fountain at United Nations Plaza, by Lawrence Halprin, contribute to the feeling of each plaza.

Four Case Studies

Mellon Square:

The case of Mellon Square was presented by Susan Rademacher, parks curator for the Pittsburgh Parks Conservancy, which oversaw the plaza’s rehabilitation. Completed in 1955 from a design by the acclaimed firm Simonds & Simonds and architects Mitchell & Ritchey, Mellon Square was Pittsburgh’s first Modernist garden plaza. By the 1980s, the site that had once been a popular urban oasis giving respite to local office workers had been left in relatively poor condition, which led to work in 1989 that diminished the plaza’s integrity. Efforts that began in 2008 would see some 80 percent of the plaza rehabilitated, based on extensive documentation, use analysis, and public engagement, along with ongoing stewardship and programming issues. The consultants to the conservancy included Heritage Landscapes, which led the design and construction team with Pfaffman + Associates (architecture), Atlantic Engineering, Hilbish McGee Lighting Design, and Mortar & ink (interpretation design).

Mellon Square - Photo © Richard Schiavoni, courtesy The Pittsburgh Parks Conservancy, 2014

Cowles Commons:

The case of Cowles Commons (along with that of Lever House and the Time-Life Building) was presented by Ken Smith, FASLA. Originally called Nollen Plaza and designed by Sasaki Associates, Cowles Commons is part of a two-block development that began in the late 1970s in Des Moines, Iowa. By the 2000s, the plaza had fallen into disuse. A key design issue in the rehabilitation was dealing with a diagonal wall that physically divided the plaza into two parts. Led by Ken Smith Workshop, the design team, which included Fluidity, James Urban, and others, developed a solution that grew out of a 2008 charette led by Des Moines City Planning staff and Cal Lewis.

Cowles Commons, Des Moines, IA - Photo courtesy Ken Smith

Lever House:

A landmark on Park Avenue in New York City, Lever House was designed in 1950 under the charge of Gordon Bunshaft of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM), with the landscape designed in-house as part of the architectural composition. Designer and artist Isamu Noguchi created several design studies for the plaza and gardens, but his work was never executed. Photographs made by Ezra Stoller during and after the building’s construction provided important visual evidence of the original design. When Ken Smith Workshop was commissioned to work on the landscape during the building’s restoration in 1999, the plantings had devolved into a mish-mash of remnant elements that bore little resemblance to the original design. Working with Gavin Keeney, who conducted the historical research, and in consultation with the Noguchi Foundation, a plan was developed to realize the original Modernist landscape concept with the addition of sculptural seating elements designed and detailed by Noguchi but never installed. In restoring and rehabilitating the landscape, some interpretation and modification was required, with the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission ultimately approving the project.

Lever House, New York City, NY - Photo by Peter Mauss, 2004

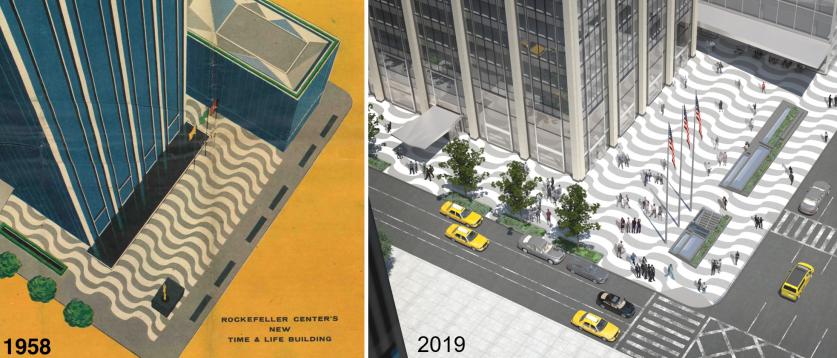

Time-Life Building:

Designed by Harrison and Abramovitz, the Time-Life Building at 1721 Avenue of the Americas opened in 1959 as the first of the urban renewal buildings, including the X, Y, and Z buildings, stretching along four blocks of the plaza-lined avenue. The building’s landscape is distinguished by a bold pattern of “Copacabana” terrazzo paving that extends from the plaza through the building’s interior lobby. A series of alternate design studies was done for the plaza features, and, in the final iteration, a large rectangular fountain was placed against the building’s facade in the front plaza. Working with Pei Cobb Freed Architects, Ken Smith Workshop collaborated on the restoration and rehabilitation of the design of the plaza and associated streetscape areas. Although the plaza itself was neither designated as a local landmark nor regulated as a public space, the significance of the original design made a sympathetic approach to the landscape a priority. The work aimed to strengthen the image and function of the public spaces. One result was a better-defined public space that includes the signature “Copacabana” paving (which had previously stopped at the properly line) extending curb-to-curb in keeping with the precedent of the subsequent X, Y, and Z buildings. The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission and the Public Design Commission approved the project.

Time-Life Building, New York City, NY

Graphing the Contexts

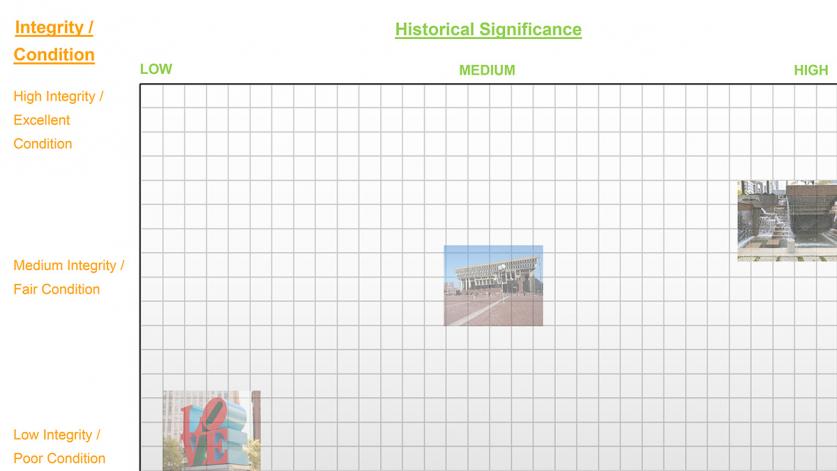

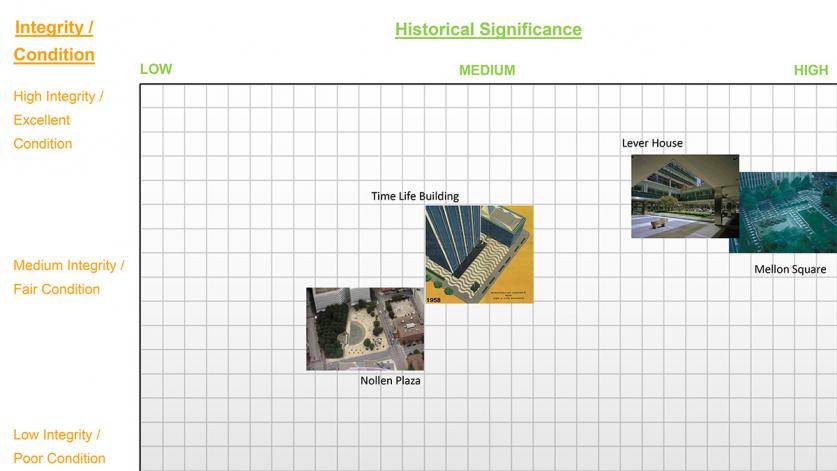

Placing these four projects on a simple line graph serves as a visual shorthand for the overall approach that guided each rehabilitation.

Each of the four case studies is placed on a line graph charting their historical significance (horizontal axis) and integrity (vertical axis), reflecting the varying approaches to their treatment.

Key Takeaways

- The rehabilitation of an historic designed landscape has the potential to offer more value than a do novo design.

- When rehabilitating postwar plazas, it is critical to establish thoroughly the site’s historical context and its level of integrity.

- Integrity refers to the plaza’s ability to convey its significance and is not the same as its physical condition.

- Aspects of a site’s integrity are distinct but interrelated.

Every historic landscape has a certain carrying capacity for change, and understanding that capacity is the necessary first step in any successful rehabilitation--a step in the direction of both responsible stewardship and great design.