Threat to Weyerhaeuser Campus Increases

It was a lightning-bolt moment in the January 15, 2021 Section 106 meeting about the proposed construction of the first two of five warehouses on 132 forested acres of the iconic Weyerhaeuser site. Legendary landscape architect Peter Walker declared that his work on the Modernist gem was “more remarkable than anything I’ve worked on,” to which he added, “and I’ve worked on some pretty interesting stuff.” Not just stuff, mind you, but internationally lauded projects including the National 9/11 Memorial (co-designed with Michael Arad) and many, many others. He went on to describe the campus as a “jewel” and to say, “there’s nothing like it in the world.” It made the follow-up by Dana Ostenson, executive vice president with the Los Angeles-based developer Industrial Realty Group (IRG) that owns the site, all the more disconcerting: “We can’t change the footprint or the design” of the proposed warehouses.

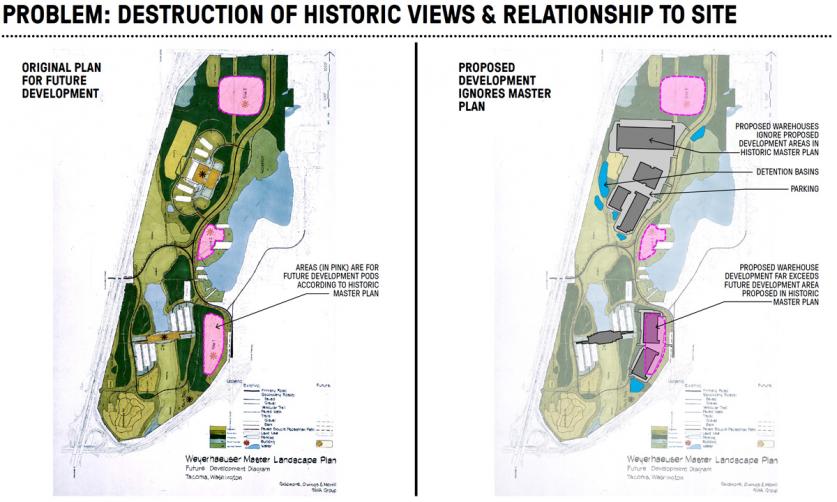

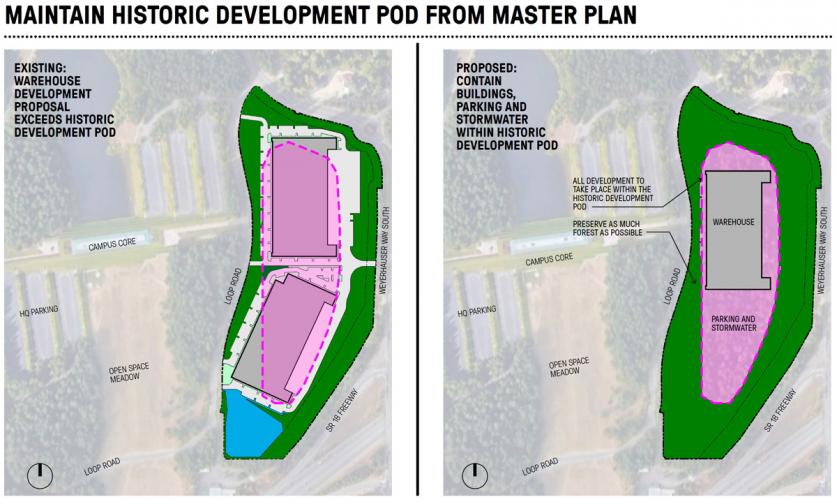

At the request of The Cultural Landscape Foundation (TCLF), Walker, architect Craig Hartman with Skidmore Owings & Merrill (the original architects for Weyerhaeuser), and landscape architect René Bihan principal at SWA’s San Francisco Office, created an analysis of the proposed development. Citing the mid-1970's master plan, they showed how several areas on the 425-acre campus had been identified as areas for possible development. However, as Bihan noted, their analysis concluded of the IRG proposal it’s “obvious that there’s too much development on too much site.”

Threats to the Weyerhaeuser campus led to its designation as a Landslide site in 2016. At the time, a 314,000-square-foot (or 7.2-acre) fish-processing plant on a nineteen-acre forested area adjacent to the headquarters building was proposed. That gave way to a more drastic and consequential proposal, the construction of 1.5 million square feet of warehouses on 132 acres – two warehouses adjacent to the headquarters building in the campus’ historic core and three more in the northern part of the site.

The campus in Federal Way, Washington, which was completed in 1972, was ahead of its time in merging Modernism with environmental sensitivity. Unlike other corporate campuses of the era, Weyerhaeuser was open to the public and was designed to include an extensive network of pathways. Walker termed the site a park that was gifted to the city by Weyerhaeuser. The campus is also notable for the synthesis of building architecture and landscape architecture. As Hartman observed in the presentation: “the landscape and architecture are absolutely inseparable” … “if you take away the landscape there is no architecture.”

IRG’s proposal was approved by the Federal Way Community Development Director, but it has drawn widespread concern from local, regional and national organizations including: Save Weyerhaeuser Campus; the Washington Trust for Historic Preservation; Rainier Audubon; Historical Society of Federal Way; SoCoCulture; Docomomo U.S.; the National Trust for Historic Preservation; and many others. During a Q&A following the presentation, Allyson Brooks, the State Historic Preservation Officer summed up the situation by first saying “this is obviously a nationally important landscape,” before asking “how do we balance the need for the [warehouse] square footage with the need to preserve the landscape?” Brooks also floated the idea of a design charette. IRG’s Ostenson, however, was not interested. In fact, he struck a somewhat ominous tone: “Unless the campus and the [headquarters] building become commercially viable … the beautiful architecture that’s involved in the campus just isn’t going to be there.”

The Section 106 process is being managed by the Army Corps of Engineers and centers on the use of some wetlands on the campus. As Brooks observed, “the tension we’re having is that the city council pooled all the authority to approve the project, but the federal government requires the [Army] Corps of Engineers to try to attempt to do the least impact or the least harm to a historic property that they can.” Referring back to the presentation by Walker, et al., she noted “we know we’re not going to get back to the original master plan … I’m sad about it,” but concluded, “the Corps and [the State Historic Preservation Office] have … the right to try to minimize the impact as much as possible. So as much landscape mitigation and size mitigation that we can do to minimize that impact is what I would like to see.”