WWI Memorial in Pershing Park Takes Final Form

The efforts to create a new World War I memorial at Washington, D.C.’s, Pershing Park began in earnest with a design competition announced in May 2015 that generated more than 350 submissions. By August, five finalists had emerged, and on January 26, 2016, the World War I Memorial Commission announced the winning design, The Weight of Sacrifice, by architect Joe Weishaar and sculptor Sabin Howard. With news of a competition winner, the Washington Post’s Philip Kennicott noted that “anyone who has watched the extended process of creating a memorial in Washington knows that the design could evolve greatly from what it is now.” Those words would prove prescient.

Weishaar’s original vision for the memorial included an 81-foot-long sculptural relief wall that framed three sides of a raised rectangular lawn—an at-grade ensemble that would have obliterated the large pool, cascade fountain, and amphitheater-like seating at the heart of Pershing Park. With its enclosed central space, the design would have likewise entirely altered the landscape’s character-defining visual and spatial relationships. Indeed, as the Washingtonian reported about Weishaar’s design, “the only element of the original park that will be retained is the statue of General John Pershing.”

Opened in 1981, Pershing Park was designed by landscape architect M. Paul Friedberg as an integral part of the long-range plan to transform Pennsylvania Avenue into the nation’s preeminent street. Friedberg is a celebrated practitioner who was named a Fellow of the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA) in 1979 and went on to win his profession’s top honors, including the ASLA Design Medal in 2004 and the ASLA Medal, the society’s highest award, in 2015. Given Friedberg’s stellar career, it is no surprise that Pershing Park was officially determined eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places in July 2016—something that the National Park Service (NPS) had forewarned the competition jury about in January of that year, before the competition’s winning design was announced.

But what had been clear to the NPS and the preservation community about the park’s pedigree only began to crystalize publicly in a succession of tense design reviews before the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts (CFA) and the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC), where it soon became evident that any new WWI memorial would have to respect the “signature elements” of Friedberg’s design. Initially, that was perhaps not as obvious to the World War I Memorial Commission as it otherwise would have been, because the park had suffered greatly as a result of years of deferred maintenance. Its animated fountain, whose soothing splash had quieted the noise of surrounding traffic, no longer functioned, the once-shimmering pool—which doubled as an ice skating rink in winter—had for several years been dry, and the lush and leafy oasis that regularly attracted scores of lunch-time onlookers (thanks in some measure to a planting plan by Oehme, van Sweden) had become a bleak repository of refuse and detritus. But the bones of Friedberg’s Modernist landscape were still undeniably there.

Thus the original Weight of Sacrifice began its long and slow transformation to the design that was finally approved by the CFA on April 18, 2019, bringing to an end an incremental tug-of-war that witnessed some seven different plans for a “pool and plaza” concept, which included an ever-shrinking sculptural wall—from 81 to 75, then 65, then 56.6 feet long—that alternated between an engaged and freestanding edifice before finally arriving at the latter. Along the way, the WWI Commission enlisted landscape architect David Rubin as a consultant, who was introduced in early 2018 to help steer the flagging review process back on track.

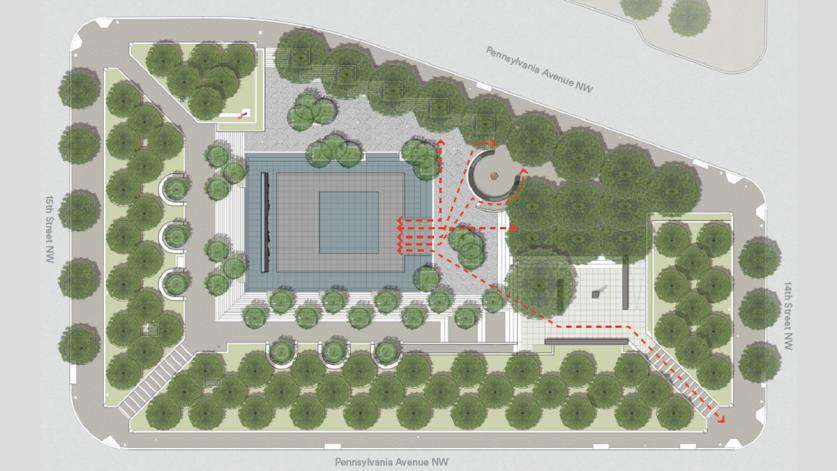

The recent CFA meeting thus marked the culmination of an iterative exercise by which a Modernist public park, worthy of the National Register, will become the site of a contemplative war memorial. The outline of Friedberg’s pool basin will remain, and the amphitheater-style seating will also be kept in place and repaired, as will the park’s paving. The planting plan will be respected, with materials replaced in-kind to “perpetuate the historic landscape design.” The footprint and shape of the park’s original kiosk will be echoed in a new circular belvedere—a viewing platform that will also contain interpretive features. And a variety of documentary and interpretive materials about the park’s original design will be produced and made publicly available, including a Historic American Landscape Survey (with measured drawings, photographs, and narrative history), a Modernist landscape study, and the park’s nomination to the National Register of Historic Places.

Many of the visual and spatial relationships that characterized the park’s original design will also be honored in the new scheme. Notably, the high berms that edge the southern and western perimeter of the site, designed by Friedberg to buffer the multi-lane traffic just beyond, will remain in place. Although they were once disparaged by the World War I Memorial Commission as foreboding and isolating elements that severed the landscape from its urban environment, the berms have now been declared an asset—"the huge advantage of the site,” in fact, according to comments made during the commission’s presentation on lighting the park, at the recent CFA meeting.

A new hardscape enveloping a square scrim of water will, however, take the place of a considerable area of the original pool basin, which will be reduced in depth and entered via a walkway/bridge on the east that is shifted slightly south of the pool’s longitudinal axis. The cascade fountain, on the western side of the pool, will be replaced by a freestanding wall that supports a narrative sculptural relief cantilevered over a base that doubles as a fountain. Water will also flow over the western (rear) façade of the wall, which will bear an inscription. Owing perhaps as much to fatigue as forethought, the length of the sculptural wall was extended by 22 inches at the recent CFA meeting, where an edifice 58.3 feet in length, with figures that are 6.5 feet high, gained final approval.

One of TCLF’s major—an often repeated—concerns about the sculptural wall was that it would visually and spatially divide the park, creating an awkward zone behind the western perimeter of the pool where visitors would be confronted by a monolithic, nearly blank, stone canvas—essentially the back of an artwork. It was for that reason that a drum-like sculptural relief, to replace the round kiosk, seemed an appealing alternative, but one not ultimately pursued by the design team or championed by the CFA. One also wonders whether the gushing waters of Friedberg’s fountain will be missed in the re-envisioned, contemplative space. Conceived as a way to drown out the noise from the surrounding traffic and streetscape, the fountain will be replaced with a much gentler—and presumably quieter—fall of water.

Even so, the approved memorial design can be claimed as a shared victory by all involved because there was compromise all around. TCLF’s advocacy of Pershing Park was never about preserving the landscape—or the past—in amber; it was about appropriately managing the inevitable change that confronts all types of cultural resources that comprise a living city. The Section 106 review process (in which TCLF was an official consulting party) is often an arduous affair, whose slow progress is marked by reams of letters and testimony and seemingly innumerable meetings, but ultimately one that can bring resolution. It is also a messy and, at times, adversarial process, which is to be expected in any endeavor in which the public is truly given a voice—much like the very democracy that we are afforded by the sacrifice and heroism that the new memorial will commemorate. For three decades, Pershing Park, as originally conceived, served its purpose well as an oasis of respite from the summer heat and an animated recreational space in winter, all set amid a bustling urban landscape. What has been averted is a radical intervention that would have erased all evidence of that success. Only time will tell whether the new World War I Memorial will achieve its altogether different goals, but we should all hope it will.