The Trails of the Weyerhaeuser Campus

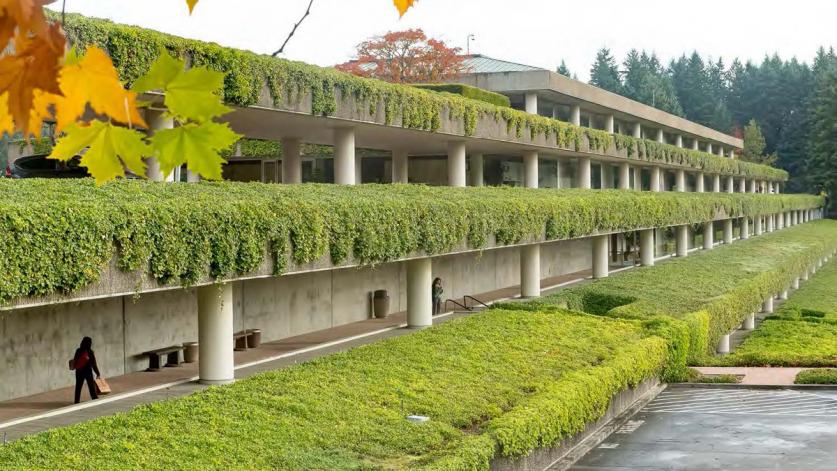

The more than 490-acre former Weyerhaeuser Corporate Headquarters Campus in Federal Way, Washington was the first suburban corporate office park built on the West Coast. With initial planning underway by 1964, and substantial development completed by 1971, the property centralized the Weyerhaeuser company’s headquarters and research facilities, provided outdoor laboratories in the managed forests, and symbolized in a bold manner the change in management approach by the company from resource extraction to forest management.[1]

The campus design sets lightly on the landscape and won the 1975 federal Department of Transportation’s highway and environmental competition as an “outstanding example of highway-oriented public or private enterprises which preserves the environment.”[2]

Public relations through open access

Public access to trails on the campus formed an integral part of the company’s larger approach to public relations for their managed forests and was unique for a time when other designed campuses remained closed to the public.

“I don’t think [public use] was actually encouraged, but it was never discouraged. People were always welcome there. We appreciated people. We had a lot of conversations with people in the area that would walk on [the campus] and about how much they enjoyed it.”[3] -Dave Dickerson.

During the early 1970s, “To a public increasingly concerned about preserving wilderness areas and old-growth, Weyerhaeuser helped provide a solution: more wood from well-managed forests allowed more public forestland to be available for other uses.”[4] George Weyerhaeuser, in a 1969 Sports Illustrated interview expressed his vision for the company in that “Our approach to outdoor recreation is going to be positive,” he said, “not a negative reaction to increased population pressure. In the future, as recreation needs grow, we will develop recreation as a primary land use. So will all other responsible timber companies.”[5]

Translating these values into an approach for shaping the campus landscape and forest, was described by Dave Dickerson, former Weyerhaeuser Facility Manager as,

“The whole thing that was always a conversation [was], ‘It’s gotta be a showpiece, it’s gotta last forever, it’s gotta represent what the Weyerhaeuser company’s all about.’ And that’s why I keep telling everybody, the building is nothing without the forest. If you lose the forest, you lose the building. The building is no longer that beautiful because the building was built, designed to blend in with the landscape. That’s the purpose of the ivy, that’s the purpose of the pond, that’s the purpose of everything was to make that building behave like it was in nature.”

“…And it was to be enjoyed by everyone, not just people that worked in the facility.”[6]

On the campus, Weyerhaeuser had a recreation department that centered on the health of his employees, including exercise programs created by fitness staff for employees—incorporating fitness through the trails. Recreation supported public relations by providing an amenity that also educated the public on the value of managed forests through first-hand experience.

Trails and site permeability

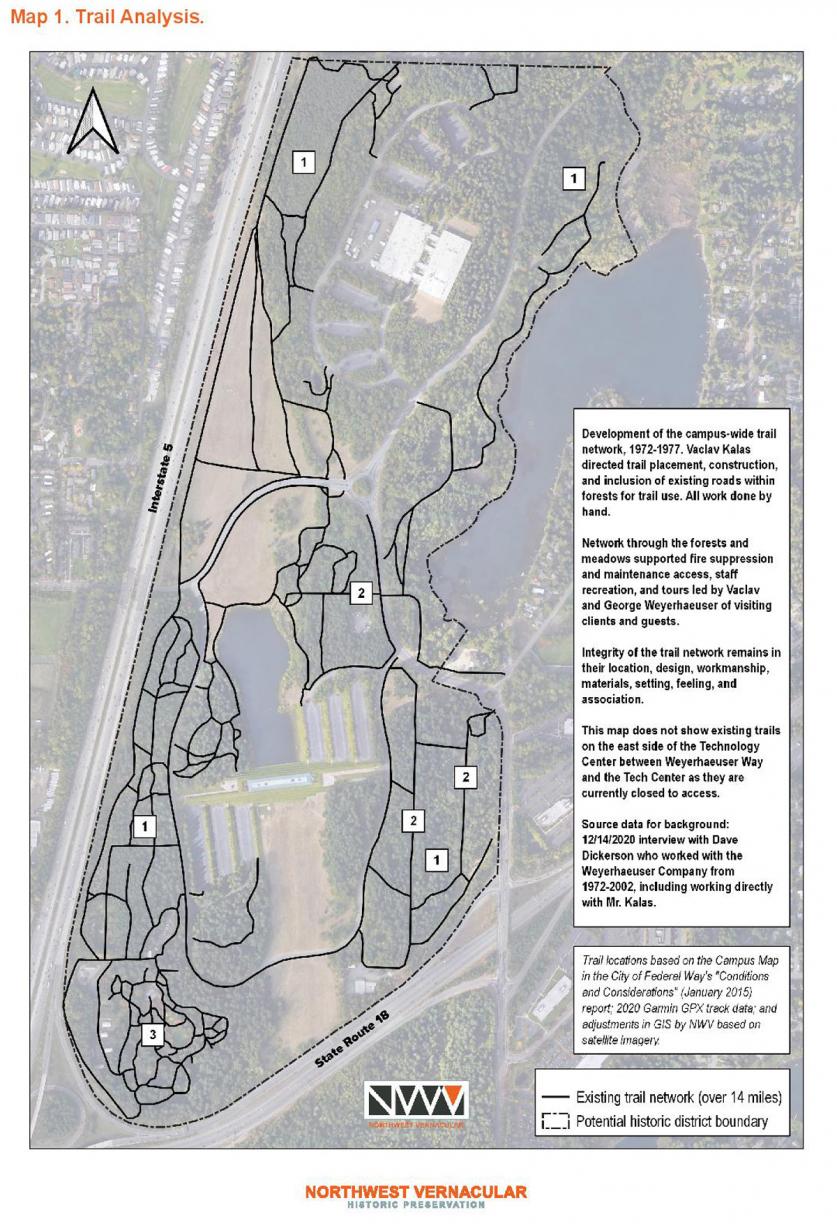

The light approach to site and trail development, and interconnectedness with surrounding areas expanded under direction of Vaclav Kalas (a trained forester, started at the headquarters forest in 1971, retired in 1986) as a show piece for the company to illustrate what the management of natural resources can do for both tree production, long-term sustainability, and recreation for the public and staff.

This work grew from the foundation of Sasaki, Walker and Associates’ (Peter Walker, partner-in-charge, core campus landscape 1969-1972, Technology Center landscape 1975-1978) landscape design that transformed the property from a cut-over forest with multiple existing roads and houses into a fully designed site. One that connected with the surrounding forest and integrated notable works including those by landscape architects Richard A. Vignolo (roof garden, 1974), William Callaway and Stephen Wheeler (John Shethar Memorial Garden, ca. 1989), and Thomas L. Berger Associations (Pacific Rim Bonsai Collection, 1989).

The relationship between George Weyerhaeuser and Vaclav Kalas (known as Vac, pronounced “Vas”) supported the landscape as it matured. Weyerhaeuser drew from his involvement with Sasaki, Walker and Associates in shaping the landscape design and his corporate leadership. Kalas brought experience in European forest estate management.

“From my understanding, [Vac] and George talked and they decided to have Vac more involved in what the landscaping was going to look like, what kind of tree plantings were going to be there. … George wanted a forest that would last forever around the site. That’s why [Vac] put a lot of different varieties of trees around there, so that if one got a disease you wouldn’t lose all of them.”[7] -Dave Dickerson

This stewardship included maintaining commercially thinned stands of second- and third-growth Douglas fir and Western hemlock, comparative un-thinned areas, a tree nursery for regeneration, selective tree removal to turn groves into mixed forests, and planting of cloned and selectively bred Douglas firs.[8] Vac had his crew remove many alders that had been planted around the site as well as ones occurring naturally in the forest. He introduced a lot of specialty trees, including pines, sweet gum and different varieties of oak and birch.[9] This consistent work produced the managed forest character.

Dave Dickerson, hired as a member of the grounds crew in 1972 and other members of the grounds crew built the campus trails, planted hundreds of trees, maintained the trails and constructed the Rhododendron Species Botanical Garden. The campus trails were purposely designed,

“primarily for employees so they could walk around the campus in the woods, rather than walking along roads. The trails were designed to connect all parts of the campus.”

“We started building [the trails] really right away, once we got everything else planted.” All the trails were created by hand, with no equipment used. “It was a real manual job. We hand-made every single one of those trails. That was kind of Vac’s object. He didn’t want to go in and destroy the woods. He wanted things to be as natural as he could.”[10]

The main trails “would kind of go through the middle of the woods” both for recreational purposes and

“to be almost like a fire trail if we had to get equipment and things down inside there, that we could. So they had kind of a dual purpose. Basically you’ll see that most of them kind of go down the middle of the forest in most places, the main trails.”[11]

In the southeast corner of the campus, there were “a couple of main trails … one that was an ex-old road and we turned into a trail. The trails were designed so that

“any level of the [headquarters] building that you went out of — no matter if it was out of the back doors or out of the front doors — you could pick up a trail and go anywhere without having to go on the streets,” or have very minimal need to use the streets. “It was to let people enjoy the woods, not to have a street to contend with.”[12]

Soon, members of the public began parking on the streets adjoining the campus and using the trails.

Demonstration of a shift in company vision

George Weyerhaeuser is recognized nationally for his role in changing both the practices and public image of the Weyerhaeuser Company from resource extraction to a forest management corporation during his 1966-1991 tenure as company president.[13] Collectively the development of trails and approach to campus design and stewardship convey this shift making the property of exceptional value in understanding the influence and complexities of the Weyerhaeuser Company’s corporate identity.

The ethos of Weyerhaeuser’s approach is conveyed in the conservation practices, landscape architecture, and architecture of the Weyerhaeuser Headquarters Campus of which he was directly involved and exerted a significant influence. As Jory Johnson and Felice Frankel, authors of Modern Landscape Architecture: Redefining the Garden, state “the boldness of Weyerhaeuser’s planning and design, as well as its northwestern sensibility, owes much to George Weyerhaeuser, the great grandson of the company’s founder, who became president and CEO in 1966.”[14]

Due to the massive scale of their national land holdings, the company’s policy and public image shift from resource extraction to forest management under the guidance of George Weyerhaeuser had a ripple effect of change in forest management practices through the national and international forest industry.

This change was deliberately and publicly symbolized in the landscape architecture of the Weyerhaeuser Corporate campus to serve as the corporation’s public image, immersion of staff in the corporate ethos, and provide marketing for visiting clients. Site location along and view connections from Interstate 5 and State Route 18, of and through the building were integral to the broad public conveyance of the company’s image of a corporate headquarters in a managed forest setting.

Louise Mozingo summarizes this transition in Pastoral Capitalism: A History of Suburban Corporate Landscapes, stating, “This remaking of the company’s public image and the role the “After Earth Day” [1970] and the rise of the contemporary environmental movement, many corporate estates explicitly used their landscape spaces to orchestrate an environmentally positive image of their businesses. The first corporate estate on the West Coast, and still the only one that rivals in scale and grandeur its East and Midwest counterparts, the 1971 Weyerhaeuser Corporate Headquarters outside Tacoma, Washington, further articulated the corporate estate as a vehicle for public display.”[15]

In April 1976 for Arbor Day, George Weyerhaeuser planted a “descendant” of the Medicine Creek Treaty Tree on the campus (reported in the Federal Way News, 04-18-76). Seeds collected from the original tree in Thurston County were grown in Weyerhaeuser’s Rochester nursery.

Studies of the campus and its relative role in modern landscape architecture and corporate campus design have been published in multiple journals and books, including Johnson and Frankels 1991 Modern Landscape Architecture Refining the Garden. In addition the headquarters building and campus received the following awards: National Honor Award from the American Institute of Architects (AIA) in 1972; AIA Bartlett Award for Disabled Access, 1972; and the Twenty-five Year Award from the AIA in 2001 as having “stood the test of time for 25-35 years and continues to set standards of excellence for its architectural design and significance.”

Weyerhaeuser acknowledges that, “Sometimes the recreational value exceeds the value of any other land use, and sites with historic interest should be preserved for the public to enjoy.”[16]

In the meadow just north of the headquarters building pond,

“we planted a whole bunch of lupines there. Vac would collect the seeds each year and we would plant more in that area. It wasn’t natural. It was Vac collecting the seeds, drying them out, holding them for a year and then we would go back and plant them in the spring. In the spring you’d get hundreds of visitors just to come to see the lupine. That was a big showcase.”[17]-Dave Dickerson

[1] Cardno, Built Environment Survey of the Former Weyerhaeuser Corporate Headquarters Campus, 4-9, 5-26; “Configurations in a landscape,” Interiors, March 1972: 78.

[2] “Weyerhaeuser offices honored,” The Seattle Times, Sunday, December 7, 1975: H13.

[3] Dave Dickerson, interview by Spencer Howard, Northwest Vernacular, December 14, 2020, transcription prepared by Jean Parietti, Save the Weyerhaeuser Campus, Project file 2020_019 Weyerhaeuser Campus, Seattle, WA.

[4] Joni Sensei, Traditions Through the Trees: Weyerhaeuser’s First 100 Years (Seattle, WA: Documentary Book Pub Corp, 1999), 143.

[5] Robert Cantwell, “The Shy Tycoon Who Owns 1/640TH of the U.S.,” Sports Illustrated, August 18, 1969.

[6] Dave Dickerson, interview by Spencer Howard, Northwest Vernacular, December 14, 2020, transcription prepared by Jean Parietti, Save the Weyerhaeuser Campus, Project file 2020_019 Weyerhaeuser Campus, Seattle, WA.

[7] Dave Dickerson, interview by Spencer Howard, Northwest Vernacular, December 14, 2020, transcription prepared by Jean Parietti, Save the Weyerhaeuser Campus, Project file 2020_019 Weyerhaeuser Campus, Seattle, WA.

[8] “Czech Woodsman Turns out to be Fine Managerial Timber,” The Seattle Daily Times, February 7, 1973: 10; “This Man Can See the Forest for the Trees,” The Seattle Daily Times, July 15, 1981: 23.

[9] Dave Dickerson, interview by Spencer Howard, Northwest Vernacular, December 14, 2020, transcription prepared by Jean Parietti, Save the Weyerhaeuser Campus, Project file 2020_019 Weyerhaeuser Campus, Seattle, WA.

[10] Dave Dickerson, interview by Spencer Howard, Northwest Vernacular, December 14, 2020, transcription prepared by Jean Parietti, Save the Weyerhaeuser Campus, Project file 2020_019 Weyerhaeuser Campus, Seattle, WA.

[11] Dave Dickerson, interview by Spencer Howard, Northwest Vernacular, December 14, 2020, transcription prepared by Jean Parietti, Save the Weyerhaeuser Campus, Project file 2020_019 Weyerhaeuser Campus, Seattle, WA.

[12] Dave Dickerson, interview by Spencer Howard, Northwest Vernacular, December 14, 2020, transcription prepared by Jean Parietti, Save the Weyerhaeuser Campus, Project file 2020_019 Weyerhaeuser Campus, Seattle, WA.

[13] Cardno. Built Environment Survey of the Former Weyerhaeuser Corporate Headquarters Campus, Federal Way, Washington, prepared for Federal Way Campus, LLC, July 2020: 4-4.

[14] Jory Johnson, Felice Frankel, Modern Landscape Architecture: Redefining the Garden (New York: Abbeville Press, 1991), 42.

[15] Louise Mozingo, Pastoral Capitalism: A History of Suburban Corporate Landscapes (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2011), 140.

[16] George H. Weyerhaeuser, “Letter to Federal Way Mayor Jim Ferrell and Federal Way City Council Members,” October 26, 2016.

[17] Dave Dickerson, interview by Spencer Howard, Northwest Vernacular, December 14, 2020, transcription prepared by Jean Parietti, Save the Weyerhaeuser Campus, Project file 2020_019 Weyerhaeuser Campus, Seattle, WA.