Dan Kiley - Almost Famous

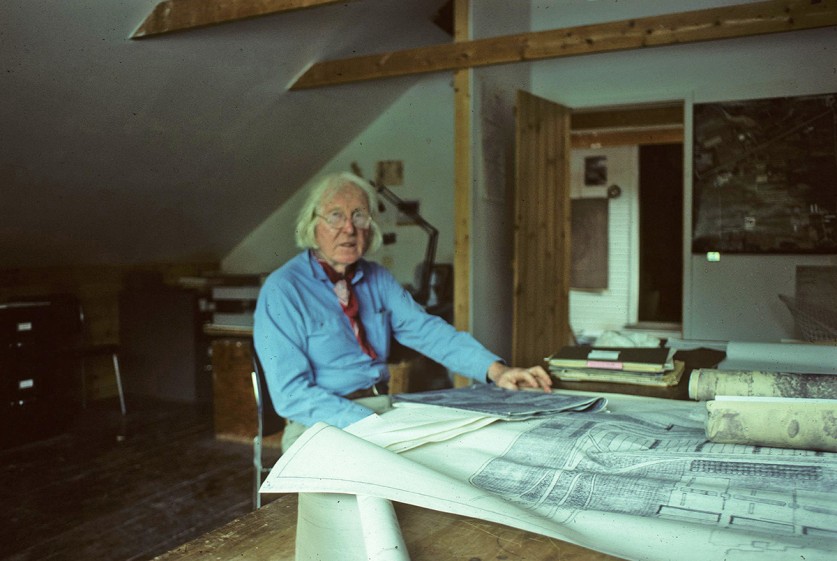

In his later years, you could find Dan Kiley with his wild hair and pants hiked up to his waist always brimming with opinions and ideas - or as the celebrated landscape architect Laurie OIin once observed: "Dan's thoughts are like rabbits - they just keep leaping out." The peripatetic, Boston-born Kiley was an avid skier who could readily quote Thoreau, Kierkegaard and Henry James. Creativity, he said, was "a patient search and a joyful discovery."

Kiley was also among the most important, influential and personally idiosyncratic landscape architects of the 20th century and designer of more than 1,100 projects - yet today he is not well known. As Calvin Tompkins wrote in his New Yorker profile of Kiley: "Even a partial listing of Kiley's more important commissions makes you wonder why his name is not better known outside the profession."

Kiley passed away nine years after that article was published. Since then, aside from the excellent Dan Kiley Landscapes - the Poetry of Space (Reuben Rainey and Marc Treib, editors), there have been no significant national or regional symposia, or any comprehensive surveys ... not even a postage stamp (Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., the only landscape architect ever honored with a stamp, was dead nearly a century before his was issued - by contrast, fifteen architects have gotten stamps). In 2012, the centennial of his birth came and went with no fanfare - in fact, no one really seems to know what remains of his built work in the US and abroad.

Regular readers know that through The Cultural Landscape Foundation, books, articles, symposia and more I'm committed to making landscape architecture and its practitioners more visible. So later this year, Landslide, my foundation's annual thematic compendium of threatened and at-risk landscapes, will focus on Kiley's extant legacy, along with an exhibition at the Boston Architectural College.

In preparation, let's take a moment to consider Kiley's most famous project, the Miller House and Garden in Columbus, Indiana - the former residence of J. Irwin and Xenia Miller. Mr. Miller was a passionate patron who made Columbus a Modernist Mecca by bringing in leading practitioners to design projects throughout the city.

The Miller home was a collaboration between Kiley, architect Eero Saarinen, assisted by Kevin Roche, and interior designer Alexander Girard. As landscape architect Peter Walker, the 9/11 Memorial designer, said of the property: ''For many of us, that was where Modernism began.'' The Indianapolis Museum of Art made one of the boldest and savviest of museum acquisitions when it acquired the Miller property, which opened to the public in 2011, making Kiley's iconic residential masterpiece accessible to all.

As a former Kiley employee, Gregg Bleam wrote: "[T]he Miller garden represents transformation ... to the use of the grid as the primary ordering device." He added: "Kiley extended the lines of the interior rooms ... to form a structure of grids that would order the surrounding gardens. By using the classical planting forms of bosques, hedges, and allées juxtaposed against flat ground planes of crushed stone or lawn, Kiley extended the diagram of the house design to the remaining site."

Ironically, Kiley's greatest education as a Modernist came not from studying at Harvard, where Walter Gropius was leading the architecture department, but from visiting European gardens, particularly great 17th century French gardens designed by André Le Nôtre. The order, geometry, and endless sweep of landscapes at Versailles and Vaux-le-Vicomte are the conceptual underpinning of his oeuvre.

If that sounds like a rigid approach to design, consider this observation from the New Yorker: "A design should grow out of a landscape, rather than be imposed on it. That is Rule No. 1 for Kiley, who doesn't suffer rules gladly. He is a functionalist, who argues that there are no universally applicable design principles, and who approaches each job as a completely new set of conditions and problems." As Kiley put it: "[the] thing I hate is principles - rules, questions and answers, all tied up in a ribbon. That's what most people want - they want all the answers." He was also disdainful of fashionable design: "I think when people have to be amused and it's fashionable, that's when the whole thing comes apart. If you do that in architecture and landscape architecture, you're in the fashion business, doing the latest thing that titillates, and it's not that serious."

Kiley's genius involved understanding the dimensions of space. As Tompkins' wrote: "Garden design is only one aspect of landscape architecture, which concerns itself primarily with space and structure and only incidentally with garden beds, herbaceous borders, and ornamental shrubbery." Kiley talked about the spacing of trees in a landscape as being "like the windows in the Palazzo Farnese. Those things are what make it wonderful or not, the spatial proportion."

Now, for those still wondering "Dan who?" his major public projects range from Dulles Airport to the Dallas Museum of Art, the John F. Kennedy Library in Boston and the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial in St. Louis (site of the Saarinen-designed arch), the Oakland Museum of Art in California, and the South Garden at the Art Institute of Chicago. In fact, Kiley is second only to Olmsted, Sr. for sites that have National Historic Landmark (NHL) status.

Other showstoppers include Fountain Place in Dallas, NationsBank Plaza ( now called Kiley Garden), in Tampa, and the US Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, Colorado an NHL designated in 2004. That's just the beginning - there are hundreds and hundreds more: public, private, institutional, and residential.

Unfortunately, Kiley's signature grid design has proved challenging for some stewards and several important projects have been destroyed including the Third Block of Philadelphia's Independence Mall and New York's Lincoln Center. Others are threatened including his commissions for the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception in his adopted state of Vermont and the Nelson-Atkins Museum in Kansas City. Conversely, some sites are on the road to renewal, most recently Kiley Garden.

The challenge: we don't know how many projects survive and in what condition. Making matters worse, his archive at Harvard's Loeb Library is incomplete because a substantial number of records at Kiley's Vermont home and office were destroyed when the property was struck by lightening and burned to the ground.

My foundation is initiating this national dialogue about Kiley's work because landscapes are innately fragile and frequently disappear without any discourse or debate. If you know of a public or private Kiley landscape, particularly one under threat or in need of assistance, we would like to hear from you.

Postscript

While Kiley didn't like to write about his work, there are several well illustrated books that delve into his life and career including: Dan Kiley: The Complete Works of America's Master Landscape Architect by Jane Amidon and Dan Kiley; The Miller Garden: Icon of Modernism by Gary Hilderbrand; Dan Kiley Landscapes - the Poetry of Space, Reuben Rainey and Marc Treib, editors; Landscape Design: Works of Dan Kiley (Process Architecture No. 33); Dan Kiley: Landscape Design II, in Step with Nature (Process Architecture No. 108); Preserving Modern Landscape Architecture I: Proceedings from the Wave Hill Conference, edited by Charles A. Birnbaum; and Preserving Modern Landscape Architecture II: Making Postwar Landscapes Visible, edited by Charles A. Birnbaum, with Jane Brown Gillette and Nancy Slade.

This blog first appeared on the Huffington Post Web site on February 11, 2013.