The Hirshhorn Sculpture Garden Redesign: between a fait accompli and auto-da-fé?

The approvals process for the proposed revitalization of the Hirshhorn Museum’s Sculpture Garden, like other building projects in the nation’s capital, is following a well-worn path including reviews by the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC) and the US Commission of Fine Arts (CFA). And, since the Hirshhorn is eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places and part of the National Mall Historic District, there are also reviews pursuant to Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act. This is underscored by the Smithsonian’s own “policy for carrying out the Institution’s commitment to protect and preserve those Smithsonian buildings, structures, and sites in its care”, which makes clear that “Smithsonian employees are responsible for ensuring that both the spirit and intent of this policy are fully implemented throughout the Institution.”

That’s being done selectively at the Hirshhorn Sculpture Garden, a modernist masterwork designed by architect Gordon Bunshaft (1974) with a subsequent overlay by landscape architect Lester Collins (1981). On April 13, 2021, the Smithsonian decided that the Sculpture Garden Section 106 review had gone on long enough. In an “all pencils down” type declaration the Smithsonian notified “official consulting parties” to the review that they “will move the Sculpture Garden Revitalization project forward” to conclude the 106 process. In doing so, they will ignore repeatedly raised objections to avoidable negative impacts on the historic core that would be caused by the introduction of stacked stone walls and alterations to the pool area. The message is clear: The Smithsonian and the Hirshhorn have abided the Section 106 process (because they had to), but they’re just not interested in the counsel of official consulting parties about these key issues.

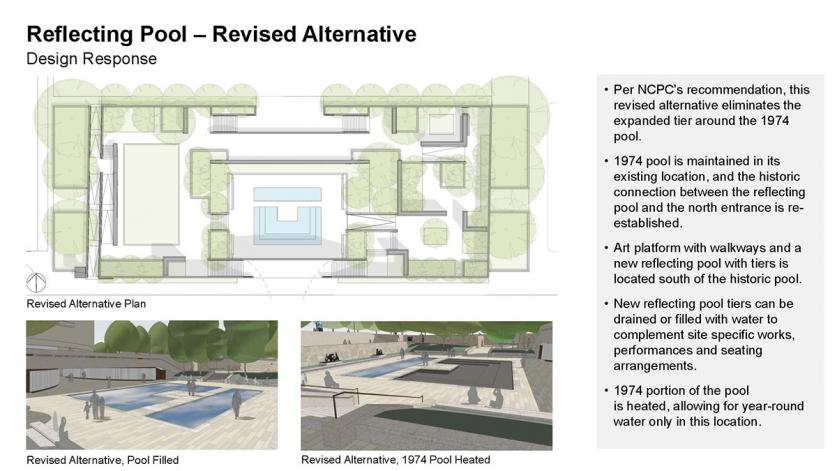

For two years official consulting parties have been largely supportive of (or silent about) nearly every aspect of the proposed redesign, except the stone walls and pool area alterations. Those are the only two changes around which The Cultural Landscape Foundation (TCLF), Docomomo US, The Committee of 100 on the Federal City, the DC Preservation League and other official consulting parties are united. The DC Historic Preservation Office has also been adamant about the stacked stone walls.

Nevertheless, the Hirshhorn has not budged at all on the introduction of the stacked stone walls. And their reconfigurations of their original pool area proposals are largely insignificant. Indeed, they have repeatedly failed to provide defensible programmatic justifications for these two design elements. Michael Lewis, in an opinion piece for the Wall Street Journal, was more pointed: "The Hirshhorn Museum’s Sculpture Garden in Washington is nearly perfect; of course, it must be destroyed."

Now the Hirshhorn and Smithsonian are hoping to muscle their way through the CFA and NCPC. The CFA has not visited this project since May 16, 2019, before the garden’s period of significance was expanded to include Lester Collins’ contributions while NCPC raised substantial concerns, especially about the stacked stone walls, during their last meeting on December 3, 2020.

Against this backdrop is a recent Wall Street Journal Magazine article by art's editor Cody Delistraty - “Hiroshi Sugimoto’s Radical Traditionalism” - with some interesting observations by and about the artist Hiroshi Sugimoto who is charged with redesigning the Hirshhorn Museum’s Sculpture Garden.

The article included a subheading with some notable declarations: “The Japanese photographer and architect, who’s redesigning the Hirshhorn Museum’s sculpture garden, is tired of modern architecture and much of the art made amid contemporary capitalism [we assume Sugimoto, the Hirshhorn and the Smithsonian agree these are statements of fact since they have not been the subject of corrections].”

So, the person engaged by the National Museum of Modern Art, as Hirshhorn museum director Melissa Chiu describes the institution, to redesign the modernist Sculpture Garden is “tired of modern architecture”? The Journal’s profile of Sugimoto prompted this tweet from the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation: “That article makes us wonder why [Sugimoto] was even considered for the project?”

It’s perplexing given the artist’s statement in 2015 about his installation in Venice, “The Glass Tea House Mondrian”: “My tea house has such a simple form. In a way, it’s like an extension of modernist studies.” And that he has labeled himself “a postmodern-experienced pre-postmodern modernist.”

Could this be calculated messaging by the Hirshhorn designed to appeal to CFA Chairman Justin Shubow and other commissioners who were appointed by former president Trump because of what Washington Post art and architecture critic Philip Kennicott says is “their ideological conformity to a rigid doctrine of architectural classicism”? For answers we can turn to then CFA meeting minutes of May 16, 2019 when the Sculpture Garden project was last reviewed by that agency: “Mr. Shubow expressed support for the design … [h]e commended in particular the proposed stone walls and the idea of providing a background for modern art that suggests ancient building techniques. He added that the stone walls would moderate the austerity of the concrete walls.” The messaging in the Journal profile suggests Sugimoto agrees with the CFA about modernism. Perhaps that’s why he said in a recent interview: “my heart belongs to ancient and medieval times.”

This may also be viewed as a move to pivot attention away from the museum’s leadership and onto Sugimoto, thereby allowing opponents to be labeled as “anti-art” and worse.

Again, the Hirshhorn and Smithsonian have repeatedly failed to provide defensible programmatic justifications for the introduction of stacked stone walls and the pool area alterations sufficient to unnecessarily alter the integrity of the original design intent.

For seasoned participants in these reviews, there once was faith in an honest and transparent process that resulted in compromise. Now, Hirshhorn and Smithsonian officials will claim, as they have previously, that the process has been transparent, even though a FOIA request had to be filed for some information and there’s an ethics complaint about the process siting with the Smithsonian Office of Inspector General.

As noted earlier, the official consulting parties have supported nearly every other aspect of the revitalization. The intransigence of the Hirshhorn over concerns raised about the stone walls and pool area alterations suggests they never had any intention of seriously negotiating these elements; indeed, they are acting more likely private property owners than stewards of a public institution. And, they are counting on reviewing agencies to endorse and give cover to their unnecessary and ill-advised choices.