Smithsonian Still Fails to do Job One in Hirshhorn Redesign

The federal review of the Hirshhorn Sculpture Garden redesign is fatally flawed because the Smithsonian officials who are managing the review have failed to do their primary and most important job. The road map for the review of a work of landscape architecture is carefully detailed in the Secretary of the Interior’s Guidelines for the Treatment of Cultural Landscapes and it starts with assessing the impact on visual and spatial characteristics (which is notably different from the guidelines for building architecture).

As TCLF’s president and CEO, Charles A. Birnbaum, wrote in an October 25, 2021, letter to the Smithsonian:

As the author of the Guidelines for the Treatment of Cultural Landscapes, I can state with great certainty that such a critical understanding of the landscape’s visual and spatial relationships has not been produced to date (the reference to views and vistas on pages 57-59 of the Smithsonian’s February 24, 2020, presentation is not an analysis of visual and spatial relationships). It is unclear whether this has been purposeful or out of ignorance on the part of the Smithsonian staff, and/or whether the project landscape architects, Rhodeside & Harwell, or any other qualified consultants, have been directed to undertake such an analysis as was done with other aspects of the undertaking.

This assessment is foundational to the decision making about the proposed Hiroshi Sugimoto redesign of the Sculpture Garden. Unfortunately, despite repeated prodding by consulting parties to the process, including by The Cultural Landscape Foundation (TCLF) and Docomomo US, Smithsonian officials have not done this primary and essential job. In fact, when queried during a July 7, 2021, Section 106 presentation the Smithsonian’s historic preservation specialist, Carly Bond, responded, “there is not a specific analysis for visual relationships [emphasis added].”

The requirement to assess the impact on visual and spatial characteristics applies because the Sculpture Garden, originally designed by architect Gordon Bunshaft with a subsequent overlay by landscape architect Lester Collins, is eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. Making that assessment requires proficiency with landscape architecture and landscape history, which are specific skill sets. The Smithsonian has already demonstrated a deficiency in their understanding of landscape architecture and landscape history when they claimed that the work of landscape architect Lester Collins was not eligible for listing in the National Register (for context, TCLF first made the case for assessing the significance of Collins’ contribution in 2015). When pushed the Smithsonian ultimately engaged a landscape history consulting firm that affirmed the importance of Collins’ work (which meant the Smithsonian’s in-house historic preservation experts were wrong).

As to the need for assessing visual and spatial characteristics, Smithsonian official can’t say they weren’t told. In an October 25, 2021, letter to the Smithsonian, Docomomo US stated: “The Cumulative Assessment of the Impacts on Visual and Spatial Relationships that were initially requested in our November 6, 2020, comment letter are still missing. This is the most critical analysis [emphasis added].” Moreover, TCLF’s October 25, 2021, letter to the Smithsonian stated: “On at least four separate occasions since the beginning of the Section 106 review process, including in our letter of October 6, 2021, we have pointed out that the principal work of this Section 106 review has not been done, namely assessing the impacts on visual and spatial relationships.”

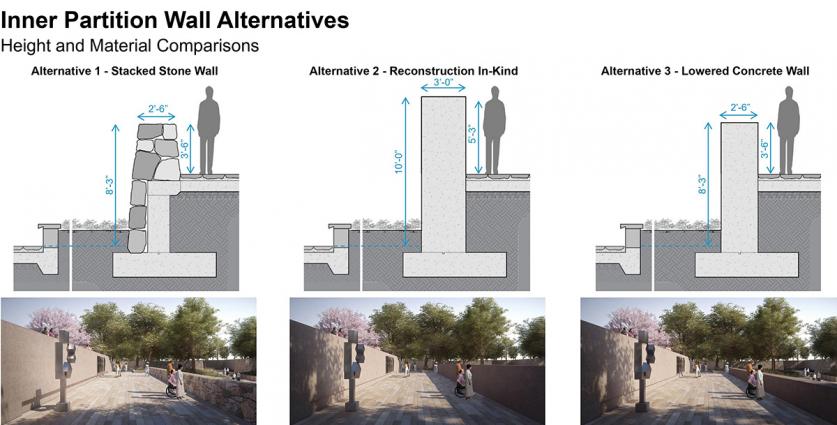

Nevertheless, the Smithsonian is not only pushing to complete the process, but they’re also asserting some of the proposed changes maintain “visual and spatial relationships” without providing any analysis or other documentation to substantiate the claim. In fact, their October 20, 2021, memorandum to consulting parties uses language that suggests the review process has all but concluded: “The Smithsonian Institution thanks you for your participation and engagement in Section 106 consultation and assistance in the resolution of adverse effects for the Hirshhorn Sculpture Garden Revitalization.” This led another consulting party, The Committee of 100 on the Federal City, to write that it “infers that the ‘final die’ is cast … and that further discussion or comment [is] futile.”

The Smithsonian’s hubris is not surprising. They got lucky with the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts (CFA), an important and influential reviewing agency that underwent a shakeup earlier this year that left the seven-member commission without a landscape architect for the first time in some twenty years. The newly appointed chair, helming only her second meeting, outsourced the CFA’s responsibility by securing the personal opinion about the proposed redesign from a landscape architect who had not previously been part of the review process and was apparently provided with limited information. As Birnbaum observed following the CFA’s July 15, 2021, vote, the Smithsonian and the Hirshhorn “benefitted from the commissioners’ very evident lack of understanding of landscape architecture.”

On December 2, 2021, the Smithsonian and Hirshhorn are expected to present a narrow set of design proposals to the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC) at which they’ll also likely trumpet their success at the CFA and the pending completion of the Section 106 process (the latter would require sign off by the Advisory Council in Historic Preservation and the D.C. Historic Preservation Office, among others). Now, the Section 106 process is not the purview of the NCPC; however, what is being presented to that body is a product of the Section 106 process. In essence, NCPC is being asked to ratify a design option based on fundamentally flawed and incomplete work by the Smithsonian.

So, ignore Smithsonian officials when they say: “Consultation occurred on this project over an extended period with seven consulting parties meetings and reviews of several supplemental informational packets.” Holding meetings to push an agenda based on flawed and incomplete research and analysis is disingenuous at best. Indeed, in the past, we have questioned whether Smithsonian officials have met the spirit of the law. By failing to do the most important identification and analysis of character-defining visual and spatial relationships (foundational to managing change in a historic designed landscape), we also question whether Smithsonian officials are fully adhering to the principles of the National Historic Preservation Act.