With a history of settlement dating to 1889, the Buckner Homestead Historic District in North Cascades National Park comprises a complex cultural landscape intimately tied to the early pioneer settlements, mining booms, and apple industries of the Pacific Northwest. The cultural landscape is the setting of hayfields, pastures, and historic orchards of vintage apple varieties nourished by century-old irrigation techniques that have remained largely unchanged since William Buckner first cultivated the land in 1911. Yet this historic agrarian landscape is facing unprecedented challenges in the face of climate change.

History

The establishment of the Buckner Homestead is intrinsically tied to the larger history of orchards along the American frontier. As the Pacific Northwest was settled in the nineteenth century, the newly claimed lands were planted with myriad orchards where fruit was grown for human consumption rather than for livestock feed. Apples, pears, cherries, plums, and peaches were harvested from early summer to late fall, with even the most remote farms including a small orchard of some kind. But the late 1880s ushered in a new era of comparative modernization, with orchards increasing in productivity and size while shrinking in species diversity. The orchards at the Buckner Homestead represent a rare extant example of the modern period of American fruit culture, when, between 1880 and 1945, the Buckner family established a self-sufficient commercial enterprise.

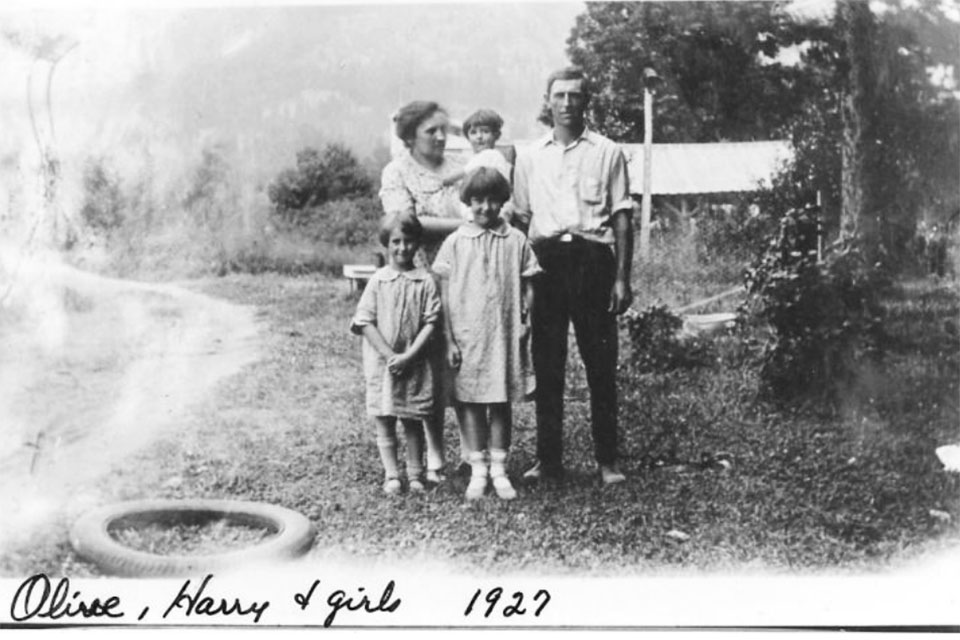

The Buckner family, photo courtesy NPS and North Cascades National Park, 1927.

The Buckner family, photo courtesy NPS and North Cascades National Park, 1927.

The early settlement of this region was initially spurred by mining, as pioneering homesteaders sought to rely on the area’s abundant natural resources. The influx of settlers and the Donation Land Claim laws of the 1850s encouraged permanent settlement and farming, effectively ensuring that riverside parcels were the most coveted and the first to be claimed. Despite the remoteness of the region, pioneers traveled by horse, canoe, and, later, steamboat to survey, claim, and cultivate land in this remote area of Washington State.

Located several miles north of Lake Chelan in a horseshoe bend of the Stehekin River, this property was originally purchased by William Buzzard in 1889. A miner, Buzzard claimed 160 acres where he built a small three-room cabin and cleared approximately one acre of the surrounding land for pasture and crop cultivation. Timber generated from clearing the land was sold to steamboats operating on the lake, while horses were lent to miners toiling in the nearby Horseshoe Basin. A small orchard was planted to provide goods to be bartered alongside other produce, like cabbages and potatoes.

But in 1910, after spending several summers at the ranch, Buzzard sold the property to William Van Buckner and his wife, Mae, who came from California on their way to Alaska, having stopped to visit Van's brother, Henry, a miner and innkeeper. The arrival of the Buckner family heralded the second phase of settlement in the region and a period of intense productivity at the homestead. Until then, only a single acre of the property had been cultivated, with the remaining land left studded with stumps in the wake of intense logging. Buckner cleared away the stumps and devised an elaborate, hand-dug, gravity-fed irrigation system to sustain his new orchard, initially occupying twenty acres. Gradually, the activities at the property grew to include vegetable gardens and extensive apple-farming operations. Although the small log cabin was enlarged and initially used as a family home, other outbuildings were required to house animals and to store equipment, tools, and produce. Comprising more than a dozen vernacular buildings, the homestead expanded to include large hayfields, extensive pastures, and a much larger orchard, with the land under cultivation growing to 50 acres.

The original three-room cabin of miner William Buzzard still stands at the Buckner Homestead; photo courtesy National Park Service, 2013.

The original three-room cabin of miner William Buzzard still stands at the Buckner Homestead; photo courtesy National Park Service, 2013.

From 1911 to 1955, the Buckners’ operations included pruning, irrigating, picking, packing, and shipping apples to other settlements in the area and the surrounding mining community. Throughout the 1940s the farm produced, at the peak of its production, approximately 5,000 boxes of apples each harvest season. Rainbow Creek, the Stehekin River, and a hand-dug concrete swimming pool provided much-needed recreation for the hard-working Buckner family.

By 1968 the U.S. Congress had created the North Cascades National Park. At the time, the Buckner Homestead was struggling to compete with the numerous orchards that had sprung up along Lake Chelan. In 1970 Harry Buckner, the son of William and Mae, decided to sell the property to the National Park Service. Listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1988 and located within the Lake Chelan National Recreation Area (a unit of the North Cascades National Park Service Complex), the 105-acre Buckner Homestead now serves as an early example of pioneer life in the region. Hemmed in by a meander of the Stehekin River along the west and south, Rainbow Creek along the east, and Stehekin Valley Road along the north, the picturesque homestead retains some twelve acres of orchards alongside pastoral land and numerous outbuildings, serving as an ideal interpretive site that is one of the best-preserved pioneer landscapes in the region. The thickly wooded, irregularly shaped site is bisected by the historic Buckner Orchard Road, which terminates in a clearing amid the orchard. Two offshoots in the form of unpaved lanes connect this central axis to the main residential compound to the northwest.

A section of the Buckner Homestead’s historic apple orchard; photo by Orygun—Flickr, 2008.

A section of the Buckner Homestead’s historic apple orchard; photo by Orygun—Flickr, 2008.

Representing the modern period in the history of fruit-tree culture in the United States, the orchard retains approximately 175 of the original 400 trees planted in the early 1920s, the last block to be planted and arranged in a characteristic 30-foot grid. Some 700 trees planted in 1911 are no longer extant, as the area was converted to hay production in the 1950s. Supporting vintage Jonathan and Rome varieties, the orchard also retains the Common Delicious apple, which, despite its name, is now a rare variety. Common Delicious is an ancestor of the globally significant Red Delicious variety, and is no longer commercially grown. Water from Rainbow Creek is still brought to the orchard via the 110-year-old, hand-dug irrigation ditch and plowed irrigation rills established by the Buckners, forming an intricate system of weirs, canals, and culverts that are still visible today.

The trees are pruned in an open-bowl style, which is highly characteristic of the era. Grafted to seedling cold-resistant rootstocks, the trees exhibit particularly short trunks with "low heads," referring to the point where the scaffold branches are attached to the trunk. “Low heading,” as it is called, became a popular technique in the 1880s and lasted until World War II, eventually being superseded by the advent of dwarfing rootstocks, a method of propagating smaller trees that grow from six to twelve feet high. A packing shed, outhouse, and the defunct swimming pool stand along the northern edge of the orchard. Other wooden outbuildings, including a barn, workshop, milk house, and smokehouse, are located immediately south of the clearing.

Threat

In 2017 the Cultural Landscape Research Group at the University of Oregon conducted a preliminary vulnerability assessment of the impacts of climate change on the Buckner Homestead landscape. The report found that the primary threats to the historic orchard are increased drought, flooding, erosion, wildfires, pests, and disease due to decreased summer precipitation and increased winter precipitation, as temperatures rise by a projected high of nearly five degrees Celsius by the end of the century. How a longer growing season and increased levels of carbon dioxide might affect the apple trees remains unknown. Although climate models may vary, invasive pests and diseases have already begun to adversely affect the site. For example, Botryspheria obtuse, otherwise known as Black Rot, has already been identified on some of the orchard’s trees. Black Rot advances when trees are stressed, so this condition is likely to accelerate as temperatures climb and precipitation patterns shift.

A shrinking snowpack in warmer winters will also affect Rainbow Creek, which is the main source of the orchard's irrigation system. Risks of floods in the Stehekin River Valley will certainly increase in the fall and winter seasons. Flooding events have already damaged sections of the orchard, and projected models indicate that a glacial outburst could cause a major shift in the river, impacting the homestead’s hayfields and pasture. As the landscape is subjected to stress from a lack of water in the summer months, vegetation will become more susceptible to insects, pathogens, and wildfires. The effects of wildfires are acute and manifold—photosynthesis, for example, could decrease due to smoke during the peak growing season, while the historic irrigation system would be affected by an abundance of sediment generated by fire erosion.

What You Can Do to Help

The National Park Service (NPS) has been caring for the orchard and the Buckner Homestead Historic District for many decades. The park’s skilled orchardist uses the historic technique of bridge grafting to repair cavities in the trunks of old trees and has been propagating replacement trees using cloned scionwood from the historic trees. The orchardist has been removing and disposing of diseased tissue, and by sanitizing tools between pruning cuts, attempting to prevent the spread of Black Rot. Park staff remove sediment from the irrigation ditches every growing season and use sluice gates to optimize the distribution of water. Slow-release, organic nutrients are introduced to address deficiencies in the soil, to try to alleviate stress on the fruit trees. Despite these efforts, the major threats that overshadow the preservation of the cultural landscape remain.

A report by the University of Oregon and the NPS titled “Study of Climate Change Impacts on Cultural Landscapes in the Pacific West Region” has outlined steps needed to help mitigate the effects of climate change in the Buckner Homestead Historic District. These include prescribed burns or mechanical thinning around the cultural landscape to reduce the threat of wildfires, restoring riparian vegetation, and bioengineering for a 300-foot-long stretch along the bank of the Stehekin River to slow the rate of erosion and reduce the potential for a major channel shift. Digging a series of wells to reduce summer water scarcity may also be necessary to adequately irrigate the orchard. To help achieve these and other measures, the public can donate to the Washington National Park Fund, which is helping to safeguard the future integrity of this and other park landscapes, or to the Buckner Homestead Heritage Foundation, which was created specifically to support and preserve the Buckner Homestead and orchard.