One of the most visited National Park Service sites in the United States, the Gateway National Recreation Area (GNRA) comprises nearly 27,000 acres of islands, ponds, marshes, and meadowlands that span from Sandy Hook in New Jersey to Jamaica Bay and Staten Island in New York City. Included among these wildlife habitats are a trove of historic sites and recreational areas that together represent a unique collection of natural and cultural resources. The future of the GNRA’s myriad resources is inextricably linked to the ecosystems that undergird the landscape, and that landscape is, in turn, increasingly susceptible to the effects of a changing climate.

History

The present-day shoreline comprising the GNRA was originally occupied by several Native American tribes. The villages of the Canarsie, who engaged in cultivation, fishing, and the manufacture of wampum (small cylindrical beads made from seashells and used as money) dotted the Jamaica Bay area, where cornfields once stretched far inland from the shore. Rockaway and Staten Island were home to three bands of Lenape Indians—the Tappans, Hackensacks, and Raritans—who were some of the first people to inhabit North America when half the continent was covered by the Wisconsin glacier. The Lenape used tulip trees to make canoes and ‘dugouts,’ hunting beavers, rabbits, turkeys, and other small animals once the glacier receded.

Jacob Riis Park within the Gateway National Recreation Area, 1956; photo courtesy MTA Bridges and Tunnels Special Archive.

Jacob Riis Park within the Gateway National Recreation Area, 1956; photo courtesy MTA Bridges and Tunnels Special Archive.

The shoreline remained under the control of the native populations until 1630, when the Dutch attempted to establish coastal settlements. This led to several wars— the Pig War (1641), the Whisky War (1642) and the Peach War (1655)—before peace was brokered and trade finally flourished between the Dutch and the Lenape. As time passed, many of the Lenape left the region, moving westward to Ohio, Indiana, Missouri, Kansas, and, finally, Oklahoma. Meanwhile, the Canarsie Indians continued to manage their land, although the Dutch Republic had incorporated much of the region (now New York City) into the colony of New Netherland by 1624, expanding outward from Nieuw Amsterdam (present-day Manhattan). With the advent of the English in 1664 and the fall of Nieuw Amsterdam, epidemics and intertribal wars ravaged the remaining Native Americans, whose numbers significantly dwindled.

In the 1700s, the rechristened New York grew in importance as a trading port. Ships entering New York Harbor skirted the shore of Sandy Hook, where there was a comparatively deep channel. To assist in navigation, the Colony of New York built the Sandy Hook Lighthouse in 1764, whose inherent strategic value would herald a spate of military fortifications along the coast. The British easily captured the Sandy Hook Peninsula, which remained under their control until 1783. The demonstrated vulnerability of the coastline to foreign attack prompted the U.S. government to purchase northern Sandy Hook from private owners. The land would play a key role in the Second (1802-1815) and Third (1816-1860) Systems of coastal fortification, as well as the Endicott Period (1885-1904) fortifications, with Fort Hancock begun in 1857, Fort Wadsworth and Battery Weed completed by 1862, and Fort Tompkins completed in 1876. Later, Fort Tilden (1917) was built as an improvement on several temporary military installations built along the Rockaway shoreline in 1812.

The surrounding vernacular landscape was almost entirely devoted to agriculture, with a diversity of crops and livestock produced by myriad small farmsteads. Grist mills, tobacco farms, and crops like potato, rye, and barley flourished in the mid-to-late 1800s. After 1875, however, the character of the land began to change as agriculture declined. Land-use patterns changed accordingly, as larger tracts were devoted to residential or industrial purposes.

The later decades of the nineteenth century ushered in the age of industrialization and modernization. Barren Island in Jamaica Bay became the center of manufacturing. The original shape of the island was roughly triangular, with industries set along the Rockaway Inlet in the east and south. Fertilizers and fish oil were the main products, while disposing of waste from New York also became a primary activity. By the early twentieth century, contamination had killed the fishing industry and refuse disposal plants came to dominate the island’s economy. The busiest seasons saw 500 to 1,000 tons of refuse arriving daily from New York, along with the carcasses of horses, cows, and other domestic animals. The smells emanating from the island became a source of constant complaint for neighboring residents, and protests from citizen groups mounted. By 1919 city authorities began reducing the quantity of waste shipped to the island, and by 1933 the last garbage plant had closed.

The site of the city’s first municipal airport, Floyd Bennett Field (in the middle-ground) was established in 1931; photo by Martin Lewison, 2015.

The site of the city’s first municipal airport, Floyd Bennett Field (in the middle-ground) was established in 1931; photo by Martin Lewison, 2015.

It was in the early 1900s that the city and private developers began to dredge the bay for sediment to be used in infrastructure projects, and to establish a port in the bay’s shallow waters. But the latter project never came to fruition, and Parks Commissioner Robert Moses pushed for the bay to become the site of the city’s first municipal airport. Floyd Bennett Field was thus established in 1931. From the latter half of the 1930s, the filling of creeks and marshland to build the Marine Parkway Bridge, Belt Parkway, and, later, the John F. Kennedy Airport negatively affected the circulation of water in the estuarine ecosystem.

" I have no desire to get into an extended argument on the subject, but it must be made clear as crystal that the old scheme to make Jamaica Bay entirely an industrial section is just plain bunk... I am even hopeful that the waters will be sufficiently purified to encourage swimming, fishing, and boating on a large scale."

Robert Moses, New York Times, 1938

Yet Moses saw the bay as an environmental resource and led efforts in 1938 to incorporate Jamaica Bay as part of the New York City Parks Department. He appointed Herbert Johnson as the first manager of the newly created Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge, who went on to develop several artificial habitats in the bay landscape. Although by this time water quality had greatly deteriorated because of extensive dredging and development, new federal legislation in the form of National Environmental Policy Act (1969) and the Clean Water Act (1970) would prevent future dredging.

The development of Jamaica Bay as a wildlife refuge in the 1950s, coupled with the end of the Cold War and the concomitant withdrawal of a military presence, prompted the need for wise stewardship. In 1969 the Regional Plan Association proposed a new national seashore in the New York City metropolitan area. The plan was subsequently modified, leading to the establishment of the GNRA in 1972 (on the same day that the Golden Gate National Recreation Area in California was established). This new large-scale area was part of a strategic effort to create more national parks near urban centers in the eastern United States, envisioned as havens for daily recreation and leisure rather than tourist destinations. The GNRA was purchased with federal funds, rather than being donated or re-appropriated from federally held lands.

The NPS administers the GNRA in the form of three units: Sandy Hook, in Monmouth County, New Jersey, and Jamaica Bay and Staten Island, in New York City. Within these three units are many distinct park sites (see below), including the Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge, Fort Tilden, Breezy Point Tip, and Jacob Riis Park in Queens; Floyd Bennett Field and Canarsie Pier in Brooklyn; Great Kills Park, Miller Field, and Fort Wadsworth on Staten Island; and Fort Hancock and Gunnison Beach on the Sandy Hook Peninsula.

Threat: The Recreation Area in the Wake of Superstorm Sandy

The land and waters comprising the GNRA have had a long history of human alteration. Industrialization and the extensive dredging of the estuarine bed from the 1900s onwards continues to present challenges to the landscape’s environmental quality. Although the area’s marshlands are capable of flushing pollutants and regenerating, extensive dumping into Jamaica Bay has overloaded the natural capacity of the ecosystem. Dredging has increased the average low-water and high-water depths of the bay, whose volume has thus increased by some 70 percent. The hardening of the shoreline and extensive residential development along the coast have also disrupted the natural circulation of water within the bay, with pollutants taking three times as long to be flushed as compared to just 100 years ago. This has adversely affected the marsh root system, accelerated sediment deposition, and slowed salt marsh formation.

Taken together, these factors have significantly compromised the GNRA’s ability to cope with the threats posed by climate change. In 2009 the NPS and National Parks Conservation Association released a report titled "Long-Term Research Management Under a Changing Climate (LRM)", which outlined the climate-related consequences for ecological, cultural, and recreation resources, as well as policy goals for climate adaptation. The report identified the primary threats to the GNRA as sea-level rise, precipitation changes, temperature increase, and extreme weather events, which will result in habitat loss, species composition, and the loss of cultural resources. According to the coastal vulnerability index (CVI), one-quarter of the Gateway shoreline is highly vulnerable to sea-level rise, with a special emphasis on Sandy Hook. Sea-level rise is also predicted to adversely affect low marshland, which provides valuable habitat for migratory birds, fish, and other fauna—especially species like weakfish and winter flounder for which the marsh vegetation provides a critical food source and nesting habitat.

"We recognize wetlands as both habitat for species and even more used as a strategy in the Northeast post [Hurricane] Sandy to buffer the impacts from storm waves and surges."Rebecca Beavers, NPS Acting Coastal Adaptation Coordinator

Rising seas also present a significant threat to Jacob Riis Park, the Floyd Bennett Field, the Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge, and Battery Weed—all low-lying resources. In the case of Battery Weed, the existing sea walls have proved to be insufficient to protect the landscape from storm surge. Similarly, Swinburne and Hoffman Islands and Miller Field are vulnerable to inundation.

At the Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge, both the East and West Ponds—manmade, freshwater ponds—were breached by salt water during Superstorm Sandy in October 2012. While damage to the ponds was repaired, the West Pond still faces significant risk from rising sea levels and extreme weather. These ponds are important places for migrating shorebirds as well as popular destinations for bird enthusiasts, and their loss would have a significant impact on visitors and wildlife alike. Furthermore, an increase in hurricane and storm activity threatens to hasten habitat loss at the GNRA, leading to the demise of freshwater species due to saltwater intrusion. Cultural, historic, and recreational resources such as the Sandy Hook Lighthouse, Officer’s Row, and Fort Hancock have already shown signs of accelerated deterioration in the wake of multiple storms, as have the beaches at Jacob Riis Park.

Below are brief descriptions of several significant sites within the GNRA.

Jamaica Bay

Located in Brooklyn and Queens and enclosed by the Rockaway Peninsula, this 19,000-acre expanse of land, bay, and coastal waters includes numerous islands, meadows, and two artificially created freshwater ponds. Jamaica Bay contains critical wetlands and habitat for migrating birds, former defense installations, the area’s first municipal airport, and recreational parklands. Although the New York City Department of Environmental Protection (NYC DEP) has already invested more than $1.5 billion in improvements to sewer systems and the restoration of Jamaica Bay and surrounding estuarine ecosystems, including 442 acres of maritime forests and 137 acres of wetlands, approximately 85 percent of the coastal wetlands have been lost in the New York-New Jersey Harbor Estuary in the past century.

Floyd Bennett Field

Floyd Bennett Field

New York City’s first municipal airport opened in 1931 in response to the pre-war growth of the aviation industry in Europe. The city-owned Barren Island was devoid of obstructions and was sparsely populated, having hosted only a small glue factory and a garbage incinerator in the late nineteenth century. Named after the naval aviator and Brooklyn resident Floyd Bennett, the 1,300-acre airport was designed with concrete runways at a time when most airfields featured runways of grass or dirt.

From 1934 to 1938 the Works Progress Administration expanded the original runways, added two new ones, and built the Coast Guard air station and a more formal airport entrance. The airfield witnessed many record-breaking flights until World War II, when it became a key resource for the U.S. Navy. It was deactivated in 1971 and soon became part of the Jamaica Bay Unit of the GNRA.

Located in southeastern Brooklyn, the field is now the largest expanse of open land in New York City and hosts an array of recreational programs attended by approximately one million visitors annually. The landscape was dramatically altered after its induction into the GNRA, now emphasizing recreation and natural resources, hosting urban camping, kayaking, ranger-led ecology walks, and community gardens. Woods and trees now occupy what was formerly open, mowed airfields, and some World War II architecture has been removed. Some 328 acres of Floyd Bennett Field were listed in the National Register of Historic Places as an historic district in 1980.

Canarsie Pier

Canarsie Pier

Originally settled by Canarsie Indians, this area was transformed into a fishing community with the advent of European settlers. In the twentieth century, the picturesque nature of the neighborhood, the construction of the Brooklyn and Rockaway Beach Railroad, and several ferry services made this a popular summer destination. The 25-acre Golden City Amusement Park opened in 1907 and hosted a dance hall, roller-skating rink, miniature railroad, and other attractions. After World War I, the influx of industries and construction of piers along the bay led to the decline of fishing communities.

In 1926 the Canarsie Pier was built by the New York City Department of Docks as part of a larger project to expand Jamaica Bay—both physically, with sand dredged from the bay, and as a center of commerce. Envisioned as a commercial dock, the pier initially projected 600 feet into Island Channel and was bounded by the Belt Parkway to the east. By the 1930s, Parks Commissioner Robert Moses curtailed industrial development, wiping out Golden City Amusement Park and integrating Canarsie Pier into his greater vision for Jamaica Bay. Reclamation of the polluted landscape by the New York City Department of Parks took place with the simultaneous construction of concession areas and other amenities.

Currently approached by a circular drive through an entrance of arching bronze letters, the pier still hosts the original concession buildings in the northeast corner. A parking lot occupies the center of the site, while along the sides of the pier, enclosed by wrought-iron railings, benches and tree-lined paths of brick, stone, and granite form promenades with sweeping views. The pier was integrated with the Jamaica Bay Unit in 1972.

Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge

Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge

Located just a half-mile from John F. Kennedy Airport and encompassing 9,155 acres of open bay, saltmarsh, woods, and brackish ponds, this wildlife refuge lies along the route of the Atlantic Flyaway and is one of the most significant bird sanctuaries in the northeastern United States. Constructed from reclaimed landfill, this wildlife refuge was established in 1951. In 1972 the refuge was incorporated into the Staten Island Unit of the GNRA, becoming the only nature refuge managed by the NPS at that time. In 2007 a 1960s-era maintenance facility was adaptively reused to create a new visitor center.

This linear refuge is bisected by Cross-Bay Boulevard, which forms the spine of the site, flanked by the West and East ponds encircled by gravel trails and marshland. The North and South gardens lie between the two ponds and just west of Big John’s pond, which features duck blinds for birdwatching. The visitor center is located at the southernmost point of the site. The natural habitats of the surrounding bay and intertidal marshes host native reptiles, amphibians, small mammals, more than 60 species of butterflies, and horseshoe crabs.

Fort Tilden

Fort Tilden

Built in 1917 as a U.S. Army artillery post, this fortification on the Rockaway Peninsula was constructed to protect the entrance to New York Harbor from naval attack. Along with Fort Hancock on Sandy Hook, New Jersey, and Fort Wadsworth on Staten Island, New York, the landscape became part of a coastal defense system for the city. After World War II, 46 barracks were converted into housing units for veterans and their families, although these facilities were vacated in the wake of the Korean War. In the 1950s the fort became a missile base. It was transferred to the GNRA by the U.S. Army in 1974.

Now known as the Fort Tilden Historic District and located on a narrow strip of land between Jacob Riis Park and the Breezy Point Tip, the landscape of maritime forests, beaches, and sand dunes is dotted with abandoned military structures and bisected by the Rockaway Point Boulevard. Several of the barracks, batteries (which housed artillery), and magazines have been renovated and host local arts groups. Battery Harris East, featuring concrete casements built to protect guns from aerial attack, has been developed into a viewing platform that provides 360-degree views of the New York Harbor, the city, and the ocean. Fort Tilden was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1984.

Jacob Riis Park

Jacob Riis Park

Situated on the western section of the Rockaway Peninsula, Jacob Riis Park occupies land that possibly did not exist until the mid-nineteenth century. The accretion of sediment gave rise to this section of the peninsula by 1870, when it first appears in recorded history. The opening of a direct line by the New York, Woodhaven, and Rockaway Railroad company between Brooklyn and the Rockaways accelerated the development of the peninsula, and the ensuing boom in recreational park development laid the foundation for the design of Jacob Riis Park. The purchase of a barren, 600-acre parcel close to present-day 125th Street by Aaron A. DeGrauw preceded the proposal for a designed park comprising “hills and valleys” surrounded by pavilions, hotels, a racecourse, and theater. In 1879 Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., was commissioned to design the landscape, but plans failed to materialize as the property passed through a series of buyers during the financial crisis of the 1890s.

Interest in the project was revived when the New York Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor, headed by Jacob Riis and William Allen, decided that the beachfront property was ideal for convalescent homes. Originally called Seaside Beach, the property was acquired by the city in 1912. Although landscape architect Carl Pilat won a design competition to develop the property, little was achieved. The site was renamed Jacob Riis Park and was later appropriated for a naval station during World War I. The park was redesigned between 1934 and 1937 under Parks Commissioner Robert Moses. Landscape architect Gilmore Clarke, of Clarke & Rapuano, New York City Department of Parks Chief of Architectural Design Clinton Loyd, and architect Aymar Embury ll collaborated on the final 1936 plan, which remains largely intact.

The linear park consists of a series of artificial and natural strips that run parallel to the beach. The focal points of the park are the ocean and People’s Beach, along the southern edge. To the north of the beach is a mile-long boardwalk known as the Jacob Riis Park Promenade, which extends from the Back Beach to the Neponsit Health Care Center at the northern end of the park. The Back Beach, which features playgrounds, lawns, ball fields, and walkways bordered by black pine, seasonal flowering plants, and shrubs, is situated north of the boardwalk. To the north of the recreational area is a large parking lot, to the southwest of which lies a golf course. The park became part of the GNRA in 1972 and was listed in the National Register of Historic Places as an historic district in 1981.

Staten Island

Overlooking the Lower New York Bay and situated in the southeastern section of Staten Island, this linear park is connected to Brooklyn by the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge, which intersects the northern swath of the site. The landscape was developed in accord with its strategic location at the entrance to New York Harbor and is scattered with the relics of military installations.

Fort Wadsworth

Fort Wadsworth

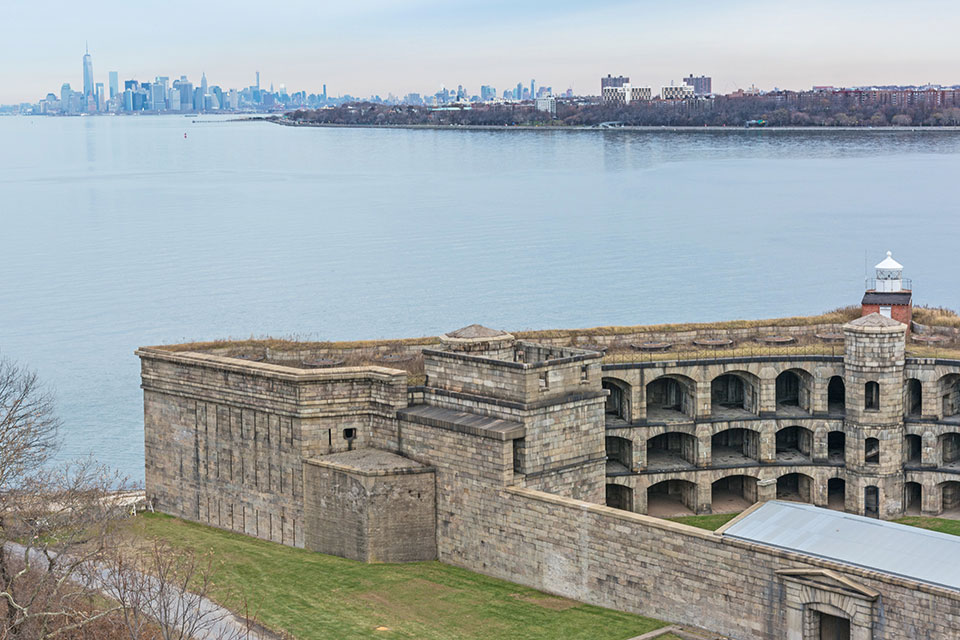

This 226-acre military installation is situated on the northeastern shore of Staten Island and is one of the oldest military sites in the United States. It is a product of the Second (1802-1815) and Third (1816-1860) Systems of coastal fortification, as well as the Endicott Period fortifications (1885-1904), featuring remnants of Battery Weed (1862) and Fort Tompkins (1876). The largely agrarian landscape of pastureland and commons remained untouched in the presence of military infrastructure due to the Second System of fortification’s emphasis on combining agricultural, defense, and recreational landscapes. Alterations during the Third System fortifications, designed by Major General Joseph Totten, included extensive grading, large areas of manicured turf, and a moat around the newly built granite Battery Weed. The Endicott Period brought the addition of a torpedo defense system and access via the railroad and streetcar.

Like other military installations along the coast, the fort experienced a lull in activity after the end of World War I. Its use as a park was encouraged by the construction of three walks extending along the overlook to Battery Weed. After World War II, the fort remained active, hosting the command control center for Nike missile systems from 1954 to 1966. Fort Wadsworth became part of the GNRA in 1994. Today, the irregularly shaped site overlooks the bay, with Fort Tompkins occupying the central swath of the landscape. A visitor center forms the western edge, while Torpedo Wharf and several batteries line the eastern coast. The Verrazano-Narrows Bridge (1959–1964) enters and crosses the site from the east.

Miller Field

Miller Field

Once owned by one of America’s most prominent families, Miller Field was originally farmland purchased by Cornelius Vanderbilt in 1836. The plot is named for James Miller, the first American flyer killed in action during World War I. Vanderbilt heirs sold the land to the federal government in 1919. The strategic location of the land made it ideal for the construction of a coastal air-defense system in 1921, including seaplane and airplane hangars, grass runways, and troop housing. An 80-acre flying field ran diagonally across the site. Used for training Coast Guard personnel, the field was closed as an airbase in 1969. Occupying the center of the linear Staten Island Unit, the 180-acre site still resembles the original landscape despite the addition of new structures and sports fields. The Miller Army Airfield Historic District was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1980.

Great Kills Park

Great Kills Park

Located in the vicinity of Lower and Raritan Bays of Great Kills Harbor on Staten Island, this 523-acre park known for beachfront recreation has a rich history. Popular for hiking and bird-watching, the site comprises four beaches—New Dorp Beach, Cedar Grove Beach, Oakwood Beach, and Fox Beach. Between 1944 and 1948, Parks Commissioner Robert Moses created the Great Kills Harbor by re-joining Crooke’s Point to Staten Island. Severely contaminated and buried in clay and sludge, the landscape that was once a repository for city sewage was reclaimed. As was common at the time, waste materials were used to fill the wetlands and elevate the property for development into a recreation area. The park was operated by the city until 1972, when it came under the purview of the NPS and was added to the Staten Island Unit of the GNRA. The park features a rich diversity of ecological resources, including the only osprey nesting site on Staten Island. Its recreational amenities include swimming beaches, a marina, a beach house, hiking and biking trails, fishing areas, and a boat launch.

Sandy Hook

Encompassing 4,688 acres of waterfront property, this linear peninsula has played a key role in coastal defense since the arrival of European colonists. Host to one of the oldest lighthouses in America, the landscape is a product of militarization dating from the War of Independence to the Cold War, against a backdrop of sandy beaches and maritime scrubland.

Fort Hancock

Fort Hancock

Developed during the Third System of fortifications, when coastal defenses were of great concern, this first fort at Sandy Hook began to take shape in 1857 but was left incomplete. Designed by Robert E. Lee, then an officer in the Army Corps of Engineers, the pentagonal fort featured two tiers of cannon with 173 guns along the seacoast and 39 guns covering the landward section. In 1885 most of the fort was incorporated into the Sandy Hook Proving Ground for weapons testing, and a new fort and seawall were built. The fort remained active through both World Wars and the succeeding Cold War, eventually including housing for some 12,000 military personnel. In 1974 the fort was deactivated and was transferred to the NPS to be administered as part of the Sandy Hook Unit of the GNRA.

Situated west of the Sandy Hook Lighthouse and south of the North Pond, the landscape hugs the western edge of the peninsula and is most distinguishable by its large central parade ground. A linear row of former officers’ quarters overlooks Sandy Hook Bay. East of these is Barracks Row, comprised of large buildings that host the Marine Academy of Science and Technology and the Mortar Battery. The Nine Gun Battery demarcates the northern boundary of the site, while the quarters of noncommissioned officers form distinct neighborhoods throughout the landscape.

Gunnison Beach

Gunnison Beach

Taking its name from Battery Gunnison (1904), the beach is located to the east of Fort Hancock. Located farther inland, Battery Gunnison provided critical defense during World War II, as U-boats and the Battle of the Atlantic came perilously close to the New Jersey shore, with some 60 percent of Allied war supplies to Africa, the Mediterranean, and Europe passing through the New York Harbor. After the battery was decommissioned in 1974, the site fell into disrepair until it was restored by the non-profit Army Ground Forces Association. Gunnison Beach is home to one of the most extensively preserved seacoast battery landscapes in the United States. Because of its secluded location, the beach became the only legal, clothing-optional beach in the State of New Jersey. The landscape also offers dramatic views of the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge and the Brooklyn Bridge, and it is the reserved breeding ground for the piping plover, an endangered native-shore bird.

What You Can Do to Help

The future of the GNRA’s myriad cultural resources is inextricably linked to the ecosystems that undergird the landscape. The NPS LRM has recommended increasing habitat connectivity, strategic land acquisition, cheaper methods of sediment trapping to control coastal erosion, improving water quality with the introduction of ribbed mussels, and monitoring the status of keystone species and invasive varieties.

In July 2018 the NYC DEP, along with elected officials, community leaders, and local stewards from Queens, announced a $400 million plan aimed at wetland restoration in Jamaica Bay to improve ecological health and deliver ancillary environmental and social benefits. If the plan is approved by the State of New York, advocates believe that restoring the wetland will increase the coastline’s resilience to climate change and protect coastal communities from storm surge while safeguarding local watersheds.

Support the work of the Jamaica Bay-Rockaway Parks Conservancy, a public-private partnership established in 2013 and dedicated to improving the 10,000 acres of public parkland throughout Jamaica Bay and the Rockaway Peninsula for local residents and visitors alike. The conservancy hosts volunteer shoreline cleanups and planting projects throughout the year within GNRA. With your support, the conservancy can continue its efforts to “expand public access; increase recreational and educational opportunities; foster citizen stewardship and volunteerism; preserve and restore natural areas, including wetland and wildlife habitat; enhance cultural resources; and ensure the long-term sustainability of the parklands.”

Support the work of the non-profit Sandy Hook Foundation, the official friends group of the Sandy Hook Unit of the GNRA, whose mission is to “provide support to programs and projects on Sandy Hook.”