Characterized by barrier islands, ridges, forested wetlands, natural levees, and marshes, the Isle de Jean Charles, which lies in Louisiana’s Mississippi Delta, became a sanctuary to Native Americans escaping slavery and the horrors of the infamous Trail of Tears (1830–1839). Descended from French settlers, the Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw community has kept their cultural lifeways alive for more than 170 years, engaging in subsistence living on their ancestral lands. But the arrival of the fossil fuel industry in the 1950s and the growing ferocity of storms in the wake of global warming have hastened the loss of one of the last Native American cultural landscapes in the region.

History

Located in Terrebonne Parish, some 80 miles southwest of New Orleans at the southernmost reaches of Louisiana, the Isle de Jean Charles is first mentioned in oral histories as an uninhabited swampland. Situated between Bayou Terrebonne and Pointe-aux-Chenes, Terrebonne Parish was cleaved from the Lafourche Interior Parish by the Bayou Saint Jean Charles in 1822. Reachable by wagon only during low tide, the island remained effectively isolated from the mainland for more than a century, making it an ideal refuge for native peoples fleeing the forced relocations of the mid-1800s.

Children enjoying a moment of leisure in the Isle de Jean Charles (date unknown); photo courtesy Chantel Comardelle.

Children enjoying a moment of leisure in the Isle de Jean Charles (date unknown); photo courtesy Chantel Comardelle.

The Mississippi River Delta was inhabited by the Chitimacha tribe for several millennia before the arrival of Europeans. Occupying the Atchafalaya Basin, one of the richest estuaries in the region, the Chitimacha villages once covered bayou, swamps, and rivers, an environment that provided natural defenses against enemy attack. Agricultural produce such as corn, beans, squash, and melons were grown and supplemented by hunting. Winter grains were stored in elevated granaries, and dugout cypress canoes were used for transport to the mainland.

When Columbus arrived in America, the Chitimacha numbered approximately 20,000. Although the tribes did not interact with colonists directly for nearly two centuries, measles, smallpox, and typhoid fever found them, nevertheless, often spread through trade, with the Chitimacha suffering high fatalities. By the time the French arrived in the Mississippi River Valley in 1700, the Chitimacha population had decreased to some 4,000—just one-fifth its former strength. Unable to keep their soldiers fed and clothed in the harsh frontier, the French relied heavily on the skills of the Chitimacha to survive. But when threatened by famine, the French raided the Indian villages for food—and women. Native retaliation eventually resulted in war from 1706 to 1718, during which most of the eastern Chitimacha were annihilated by the superior French firepower. Those who survived moved farther north along the river, finding sanctuary on a slender strip of land between Bayou Terrebonne and Bayou Pointe-aux-Chenes.

The Trail of Tears

The migration of the Biloxi-Choctaw nations to the island began against the backdrop of the Indian Removal Act and the ensuing forced relocations known as the Trail of Tears. Little is known of the Biloxi tribe before the arrival of the colonizers in 1492. But after being decimated by an epidemic of smallpox, the Biloxi of southern Mississippi are said to have moved westward into Louisiana around 1763. The influx of the French and the ensuing French-Indian War of 1764 increased the movement of the tribes within Louisiana and increased the commingling among native populations. Early treaties signed between American agents and Indian representatives both protected Indian territory and maintained the peace necessary to continue lucrative trade in fur and timber. In 1830 five ‘civilized’ Indian Nations (the Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee, Cherokee, and Seminole tribes) lived as autonomous nations in the American south. But the expansionist aims of European settlers pressured the federal government into removing the Indians to make more land available for settlement.

The ascent of Andrew Jackson, whose central legislative agenda was the removal of Native Americans, meant that the opposition of dissenters like Davy Crockett and John Quincy Adams had little effect. With the passing of the Indian Removal Act of 1830 in defiance of a Supreme Court decision, some 46,000 Native Americans from the southeastern states were displaced by U.S. Army troops and state militia from 1830 to 1839, opening nearly 25 million acres of land for settlement. The dispossessed tribes, numbering some 100,000 people, along with 4,000 freedmen, trekked westwards in ‘death marches,’ constantly exposed to disease, extortion, violence, and starvation. Fully one-third of those who marched perished along the way.

"In the whole scene there was an air of ruin and destruction, something which betrayed a final and irrevocable adieu; one couldn't watch without feeling one's heart wrung. The Indians were tranquil, but sombre and taciturn. There was one who could speak English and of whom I asked why the Chactas were leaving their country. "To be free," he answered, could never get any other reason out of him. We ... watch the expulsion ... of one of the most celebrated and ancient American peoples."Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America

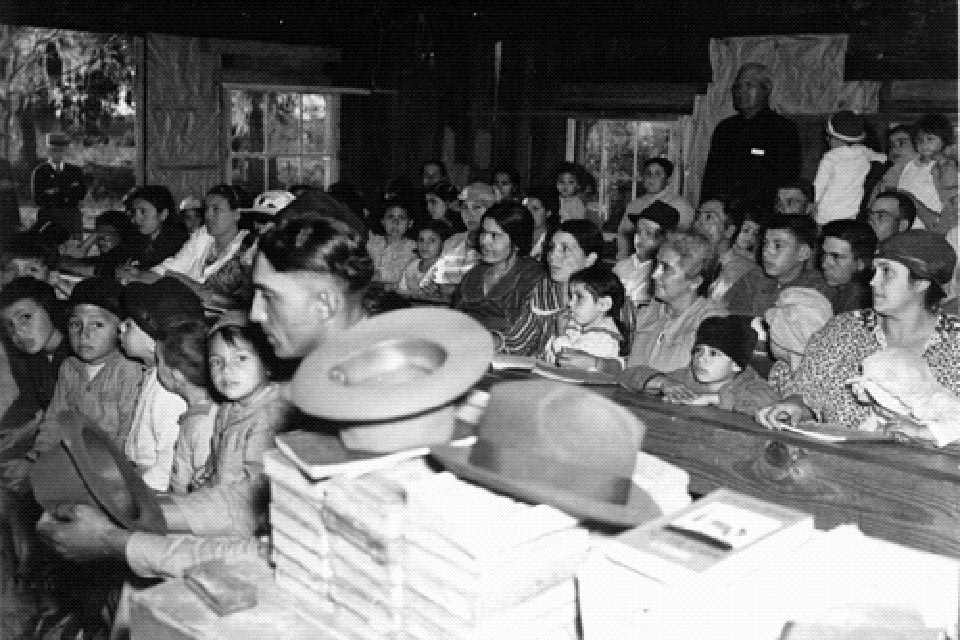

The first school serving the island was built in the 1930s on the mainland at Pointe-aux-Chenes; photo courtesy IsleDeJeanCharles.com, ca 1930’s.

The first school serving the island was built in the 1930s on the mainland at Pointe-aux-Chenes; photo courtesy IsleDeJeanCharles.com, ca 1930’s.

The Last Mississippi Indians

The word ‘bayou’ originates from the now-extinct language of the Choctaw. Although the Isle de Jean Charles remained inhabited by native peoples throughout the nineteenth century, this fact is largely erased in government records. In 1876 the area was described as “uninhabited” because the State of Louisiana did not recognize native peoples as landowners. Hence the first recorded inhabitants of the island’s community are Jean Baptiste Narcisse Naquin, Antoine Livaudais Dardar, Marcelin Duchils Naquin, and Walker Lovell. A Frenchman disowned for marrying Pauline Verdin, an Indian woman, Jean Naquin visited the area several times to assist the French pirate Jean Lafitte, who operated along the coast. The descendants of Naquin and Verdin intermarried with the Indian inhabitants, forming the first four families, comprising 77 people, to be officially recorded in the census of 1910. Sustained by a subsistence economy of farming, fishing, and trapping, the community’s original dwellings had dome-shaped roofs constructed from a mixture of mud and moss, with six-inch-thick walls covered with palmetto.

Buoyed by their ties to the land, the island’s people were largely unaffected by the Great Depression. The first school serving the island was built in the 1930s on the mainland at Pointe-aux-Chenes, the children arriving for their daily lessons on pirogues. A single-room Mission School was built on the island in the 1940s, offering an education through the eighth-grade level. Although the Island Road was constructed on marshland in 1953, forming a connection with the mainland, the only school there to admit Indian students was Daigleville Indian High School, established in 1959 in Houma, some 25 miles away. Thus many native peoples sought to conceal their race to gain admission into nearby public schools. It was not until 1967 that the desegregation of state schools granted the tribe full and easy access to education.

In the late 1920s, Texaco discovered oil in the bayous and marshlands of Louisiana, resulting in a renegotiation of land leases to benefit the oil companies. By 1929 oil was discovered at Terrebonne Parish, soon leading to offshore drilling and dredging along the shoreline. The Houma Canal was constructed in 1962, connecting the county’s only city to the Gulf of Mexico to facilitate the extraction and transportation of oil and natural gas.

The island has always been vulnerable to storm-related flooding because of its location and elevation. But drilling and the dredging of canals throughout the cultural landscape by the fossil fuel industry have accelerated the processes that are making the island sink. The topsoil of the land consists mainly of organic matter that sustains plants. The dredged canals are much deeper than natural channels and are formed by piling dredged materials on either side to make a levee. This prevents water from percolating into the island’s soil, drying and oxidizing it, and hastening the island’s subsidence. Yet oil companies form the backbone of the region’s economy and provide jobs to the island community, making it difficult to separate ecological threats from economic necessity.

Threat

The inspiration for the fictional ‘Bathtub’ community in the film Beasts of the Southern Wild, and the subject of the 2013 documentary Can’t Stop the Water, the Isle de Jean Charles exemplifies the plight of many rural communities along the Louisiana coast, where the state has been losing a landmass the size of Manhattan every year.

Characterized by dwarf palmettos, bald cypress, and sawgrass swamps, the vast 22,000-acre forested landscape that was the Isle of Jean Charles has lost 98 per cent of its landmass since 1955, leaving just 320 acres and an indigenous community on the front lines of climate change. The community’s ties to its ancestral lands and its traditional lifeways are vanishing. In 2002 the island was home to 78 households, but now fewer than 25 families remain. Rapid environmental changes coupled with stronger storms caused by climate change have led to ever-increasing flood risks. Although small levees can protect the island during high tide, a surplus of barriers has led to coastal erosion and the intrusion of salt water, killing the once-thriving ecosystem. The crumbling subsistence economy and the need for reliable access to jobs have already forced several inhabitants to relocate to nearby areas, including Pointe-aux-Chenes, Bourg, Montegut, Chauvin, and Houma. Chantel Comardelle, tribal secretary of the Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw, described the situation in these terms:

"We are displaced. Our once-large oak trees are now ghosts. The island that provided refuge and prosperity is now just a frail skeleton. For our Island people, it is more than simply a place to live. It is the epicenter of our Tribe and traditions. It is where our ancestors survived after being displaced by Indian Removal Act-era policies and where we cultivated what has become a unique part of Louisiana culture."

Abandoning an island slowly sinking into the Gulf of Mexico is an unavoidable reality. In 2016 the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development earmarked $48 million for the Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw planned resettlement, representing the first government-funded project aimed at resettling an entire community as a result of the effects of climate change—the first case of “climate change refugees” in the United States, as some have dubbed it. In January 2019 the Louisiana Land Trust purchased 515 acres in Terrebonne Parish as the site for a new community. But there are already disagreements between the tribe and the government about how such plans should be implemented, and there is little trust to build upon.

What You Can Do to Help

The Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw community on the Isle de Jean Charles will be the first community in the United State forced to retreat in the wake of coastal land loss, but it will not be the last. Visit the website of the non-profit Isle de Jean Charles to learn more about the history of the island and its people. The Isle de Jean Charles Tribe is currently working to complete the “Preserving Our Place” project, which will further document and share the history and experiences of the tribe and its community. A new museum, documentary materials, and other resources are being developed in an effort to share this “place” with the world before it disappears. More information about how to get involved in the project is available through the project’s website. While the relocation is underway, tribal citizens continue to face the brunt of ever-stronger storms. Most recently, Hurricane Barry inflicted extensive damage on the island. Contact tribal leaders to learn more about the ways in which you can help.