Located within the Blackwater Wildlife Refuge in Dorchester County, Maryland, the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Monument commemorates the site of the clandestine efforts of legendary abolitionist Harriet Tubman. Born into slavery, Tubman eventually escaped bondage only to return nineteen times to free her family and friends, going on to become the first woman to lead an armed assault during the Civil War. Although President Barack Obama established the monument in 2013 “for the benefit of present and future generations,” the coastal landscape that bears witness to Tubman’s story is now in danger of being lost forever.

History

A haven for migratory waterfowl, the iconic American bald eagle, and the Delmarva fox squirrel, the vast tidal marshes of the Chesapeake Bay region known as the “Everglades of the North” are also home to the Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge (BNWR), which, in 1933, was designated as a sanctuary for birds migrating along the Atlantic Flyway. But this cultural landscape of deep natural beauty bears witness to migrations of an altogether different variety—those fleeing from what was the northern slave state of Maryland, across the Mason-Dixon Line, to the free state of Pennsylvania.

The rich tidal marshland of the Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge was a landscape that the young Harriet Tubman knew well; photo courtesy Chesapeake Bay Program, 2017.

The rich tidal marshland of the Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge was a landscape that the young Harriet Tubman knew well; photo courtesy Chesapeake Bay Program, 2017.

Formed in the late 1700s, the Underground Railroad was a secret network of escape routes, wayside safe houses, and meeting points established by African slaves and fellow abolitionists in the United States. Running northwards from Florida along the Eastern Seaboard to the free states and Canada, the routes were lifelines for those who would dare to cast off their yoke of bondage. Aided by myriad sympathizers, including the formerly enslaved, free-born African Americans, White abolitionists, Native Americans, and Quakers, the Railroad, at its height, brought approximately 1,000 enslaved people per year to freedom. To hamper these efforts, Southern politicians lobbied heavily for the Compromise of 1850 and a stringent Fugitive Slave Law, which sought to compel officials in free states to assist professional bounty hunters in their operations. The law also deprived enslaved peoples of their right to legal defense and resulted in slave catchers kidnapping countless free African Americans—mainly children—and selling them into slavery.

Against this historical backdrop of resistance, Harriet Tubman was born into slavery in Dorchester County, Maryland, ca.1820. One of nine children, she was, from the age of five, regularly leased to nearby families for whom she worked as a babysitter or a capable field hand. Abused by multiple overseers, she suffered a severe head injury when an irate slave owner, intending to punish another enslaved person, struck her with a metal weight. Nevertheless, under the care of her family, Tubman survived and grew to become a skilled logger and an expert hunter. Facing the likelihood that her family would be sold and separated after her master, Edward Brodess, died, Tubman used her prowess as a scout and a hunter, along with her familiarity with the marshy, wooded landscape, to escape to Philadelphia in 1849. Her journey, nearly 90 miles on foot, was long and arduous. She likely followed the route commonly taken by those escaping enslavement, one that had been passed down through oral tradition. Guided by the North Star, she traveled northeast by night to avoid slave catchers, following Maryland’s eastern shore before slipping into Delaware and eventually reaching Philadelphia.

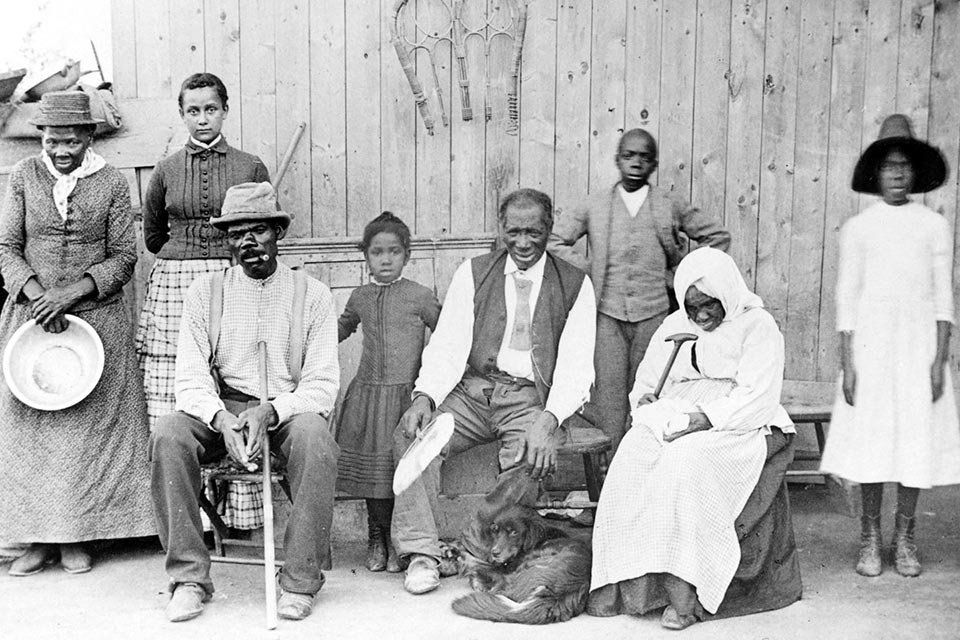

Harriet Tubman (far left) with family and neighbors, ca. 1886, in Auburn, NY; photo by William H. Cheney, courtesy Library of Congress.

Harriet Tubman (far left) with family and neighbors, ca. 1886, in Auburn, NY; photo by William H. Cheney, courtesy Library of Congress.

After working several odd jobs in Philadelphia, Tubman decided to return to Dorchester County to rescue her niece and her husband. The success of this mission emboldened her to return to the area nineteen times over the next eleven years, rescuing some 70 of her friends and family members. Her resourcefulness during these perilous rescues is well documented. She is said to have carried a pistol, urging her charges onward without turning back. Walking, riding horses, sailing on boats, and traveling by train, Tubman, who was often in disguise, would issue bribes when necessary to ensure the success of her plans. Slaveholders, meanwhile, remained flummoxed by the escapes, never connecting Tubman to the increasing success of the Underground Railroad.

"I freed a thousand slaves. I could have freed a thousand more if only they knew they were slaves."Harriet Tubman

Nicknamed “Moses” by notable abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, Tubman went on to aid both John Brown’s failed 1859 raid on Harper’s Ferry and the Union cause, where her knowledge of the landscape again proved invaluable. She became the first woman to lead an armed assault during the Civil War as part of the Combahee River Raids during which 750 enslaved people were freed. In her later years, she lent her support to the cause of suffragettes, working alongside activists Susan B. Anthony, Emily Howland, and others. Tubman toured Boston, Washington, D.C., and New York City, speaking in favor of women’s voting rights. In 1896 she established the Harriet Tubman Home for the Aged and Indigent Negroes near Auburn, New York. When Tubman died in 1913, she was buried with semi-military honors in that town’s Fort Hill Cemetery.

Characterized by rich tidal marshland, hardwood and pine forests, and freshwater wetlands, much of the landscape that Tubman knew as a youth now falls within the BNWR. Before the area’s designation as a refuge, the marshes along the river were part of a fur farm that mainly depended on muskrats. The woodlands were heavily timbered, with ditches and furrows from its agrarian past still in evidence. Located twelve miles south of Cambridge, Maryland, the 30,000-acre refuge is part of a large complex of tidal wetlands, which provide storm protection to lower Dorchester County, including the town of Cambridge, making it an ecologically significant area within the state. The Blackwater, Little Blackwater, Choptank, and Transquaking Rivers drain the region. Managed by the National Wildlife Refuge System, the refuge is home to many species of endangered plants and several species of birds, reptiles, and amphibians. Among them are three recovered species: the American bald eagle, the Delmarva fox squirrel, and the migrant peregrine falcon.

In March 2013 President Barack Obama authorized the creation of the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Monument and National Historical Park, which occupies an eastern swath of the BNWR. Comprising a composite of federal, state, and private lands along the Eastern Shore of Maryland, the parkland is bisected by the 125-mile-long Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Byway, which connects 36 significant sites along the shoreline. At the center of the byway, within the monument, lies the seventeen-acre Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Visitor Center, commemorating Tubman’s early life in enslavement and her legacy as the most successful “conductor” of the Underground Railroad. The westward loop of the byway further connects to the seven-mile-long Joseph Stewart’s Canal, constructed between 1810 and 1832 by enslaved and free African Americans. Tubman’s father, who was involved in nearby timbering operations, is said to have transported materials along the waterway. To the east, at the edge of the refuge, lie the Bucktown Village Store, the location of Tubman’s first act of resistance and childhood injury, and the Brodess Farm, where she toiled in slavery.

Threat

The historic landscape of Tubman’s youth, which includes a segment of the Underground Railroad, is an integral part of American history, recalling the efforts of abolitionists and enslaved alike, whose work paved the way for Emancipation. This mosaic of rural landscapes and agricultural easements also plays an important role in helping to absorb the impact of storm surge for southern Dorchester County, as well as the town of Cambridge.

The primary threat facing both the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Monument and the BNWR is sea-level rise. Affected by both the rising waters and subsidence, the refuge has lost some 5,000 acres of wetlands since 1938. Only twenty years ago, however, most roads along the coastal edge remained dry during high tide, but over the last two decades, every tide has begun to creep farther inland. Residents of southern Dorchester County have learned to schedule their commutes around the tides, and flooding has become a regular occurrence. Moreover, this steady rise in tide, known as “sunny day flooding,” occurs in the absence of storms, making several historic properties associated with Tubman and close to the shoreline extremely vulnerable. The sea-level rise is also increasing the salination of the groundwater, which will eventually destroy the local farms and the woodlands of the refuge. Additionally, endangered bird species with habitats exclusively in the salt marshes have also seen a significant decline in population as the coastal land sinks.

What You Can Do to Help

In December 2018 it was announced that a partnership between the Chesapeake Conservancy and the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) had led to the permanent protection of 155 acres of land as part of the Nanticoke Unit of the BNWR. In addition to the work of the conservancy, the nonprofit The Conservation Fund has also worked with the USFWS and National Park Service for decades to add nearly 8,000 acres to the BNWR, including 480 acres to the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Monument. The Conservation Fund has also played a key role in establishing the Harriet Tubman Rural Legacy Area and has backed efforts to rebuild the coastal marshes with strategies that are outlined in Blackwater 2100, a report produced along with the Audubon Maryland-DC and the USFWS.

While it is inevitable that much of the current land beneath the monument will be lost to sea-level rise, the strategic conservation of adjacent uplands will allow for new marshland to be created. This is essential to buffer communities, farms, and infrastructure from storm surge and flooding. Although new acreage has been acquired, further efforts are needed to ensure adequate space and connectivity for migratory corridors.

Donate to the Chesapeake Conservancy and to The Conservation Fund and support these organizations’ ongoing efforts to save critical wetlands and a cultural landscape that is steeped in history.