The sequoia genus of redwood trees dates to the Jurassic period and was once abundant across the northern hemisphere. Only three descendants of these trees survived the Ice Ages and are around today: the coast redwood, dawn redwood, and giant sequoia. With their thick bark and elevated canopies, giant sequoia are the quintessential fire-adapted species, but due to past forest management practices and the warming climate, these trees are now threatened by wildfires that are increasing in their intensity. Three severe wildfires have burned through giant sequoia groves in the last five years alone.

History

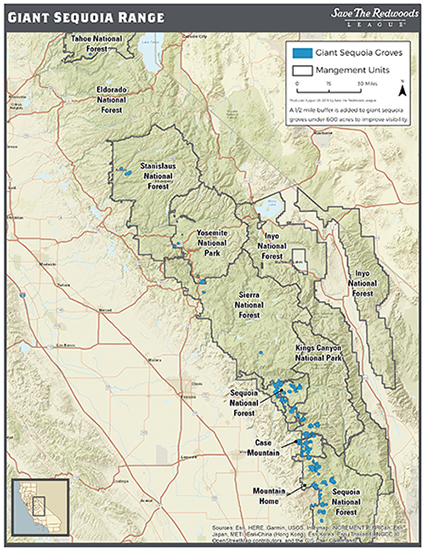

Giant sequoia (Sequoiadendron giganteum) are found within some 73 isolated groves that span approximately 48,000 acres on the western slopes of California’s Sierra Nevada mountain range. Also known as Sierra redwoods, these trees are the largest trees on Earth, growing up to 30 feet in diameter and 300 feet in height. They are also among the oldest living things on Earth, with individual specimens living for thousands of years.

Hikers enjoying the giant sequoia forest at Calaveras Big Trees State Park; photo by Max Forster, 2019.

Hikers enjoying the giant sequoia forest at Calaveras Big Trees State Park; photo by Max Forster, 2019.

While Native Americans had long revered the giant sequoia, the first records of the trees in the journals of European explorers can be traced to the 1830s. What followed was a period of heavy lumbering throughout the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as the trees were harvested for commercial use. Because of their great weight and brittleness, the trees tended to shatter when they were felled, with much of the wood lost. It has been estimated that 50 percent of the cut timber was never milled.

The threat of losing this unique species to logging prompted the federal government to protect land for the sake of conservation. In 1864 the Yosemite Valley Grant Act deeded Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Big Tree Grove to the State of California on the condition they be preserved for public use. In 1879 public outcry over logging led the U.S. Congress to establish the General Grant Grove and the Sequoia and Yosemite National Parks. Presidents Benjamin Harrison and Theodore Roosevelt took further action to protect the groves, establishing the Sierra Forest Reserve (1893) and the Sequoia National Forest (1908). Prompted largely by concerns about the potential loss of redwood groves, the California legislature established a state park commission in 1927 to explore the creation of a system of state parks. Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., was then tasked with conducting a statewide survey of lands that might be acquired for new parkland, submitting his final report in 1929. Olmsted’s work would lead to the conservation of many redwood forests, and he would remain involved in seeking their protection for decades to come.

Through the efforts of government agencies and advocacy groups, much of the range was placed into public ownership by 1940, which dramatically decreased the threat from logging. At this time, roughly one-third of the old-growth trees had been cut. In the 1980s the extensive logging in groves of non-giant sequoia within what was then the Sequoia National Forest prompted a public outcry, leading President William Clinton to create the 328,000-acre Giant Sequoia National Monument in April 2000. Today, approximately 98 percent of the Giant Sequoia Range is in public ownership. The remaining two percent exist in small private parcels scattered among eleven groves. The conservation of these trees as publicly owned resources was the result of partnerships among several advocacy groups, including Save the Redwoods League, as well as government entities.

Giant sequoias thrive in a matrix of Sierran mixed conifer forests, and they are habitat for myriad species, including black bear, mountain lions, Pacific fisher, and Sierran martens. The oldest individual specimens have been dated to more than 3,000 years old, which means that some of the Monarchs around today were alive during the peak of ancient Greek civilization, the reign of the Roman Empire, and the building of the Great Wall of China. These unique living treasures are relatively rare, but due to their immense size, they store massive amounts of carbon, which can help in the fight against climate change. They are also important cultural icons, drawing visitors from all over the world.

Threat

Giant sequoia are at significant risk from severe wildfire. Ironically, giant sequoia are a highly fire-adapted species, with thick bark and elevated canopies that enable them to withstand lower-intensity wildfires. Historically, fires burned roughly every ten years, started by lightning or Native American burning to cultivate needed resources. These frequent fires generally burned at low severity, maintaining an open forest by burning up the woody debris and some of the smaller trees and shrubs. There were also some locally intense patches in these fires, which were important for creating habitat diversity via forest openings, as well as facilitating sequoia regeneration. The heat from a wildfire cues the sequoia’s cones to open, releasing seeds onto their ideal seedbed—the bare mineral soil left behind.

But for more than a century all fires were excluded, dramatically increasing tree densities and the amount of woody debris in these forests. As a result, giant sequoia groves are now threatened by fires that are much more severe than they would have been historically. Moreover, the warming climate has been linked to increasing wildfire activity, and that trend is expected to continue. This "double whammy" is creating an imminent and critical threat to these ancient giants. In the last five years alone, three large wildfires have burned through giant sequoia groves, with terrible consequences. Save the Redwoods League initiated a study on the effects of two wildfires that burned in 2017, documenting at least 50 dead old-growth giant sequoia at Black Mountain Grove, 29 of which were greater than ten feet in diameter. Nearly 40 of these giants were killed in the smaller Nelder Grove.

The threat to the majority of the groves is thus both acute and imminent. A small number of groves have been restored through prescribed burning and mechanical thinning, which reduces fuels so that when a wildfire occurs, it will burn at lower intensity and most of the old-growth giant sequoia will survive. However, most of the groves have not experienced any fire or fuel reduction in more than a century. When coupled with the warming climate, this means that the Giant Sequoia Range is at imminent threat from severe wildfires. In addition, the severe 2012–2016 drought in California resulted in a massive die-off of non-giant sequoia that dramatically changed the structure of these groves, leaving behind dead trees that, in the long run, will increase fuel loads.

Resource managers, particularly in national parks, have been working to restore fire to these ecosystems since the 1970s. This work has been slow because of limited staffing and public funding, which is why so few groves have been restored to date. Restoration via prescribed fire, managed wildfire (allowing natural lightning ignitions to burn for resource benefit under prescribed conditions), and restoration thinning are the critical tools that can restore these forests so that they are as resilient as possible to the changing climate.

What You Can Do to Help

The public can help support these efforts by asking their state and federal legislative representatives to increase funding for the restoration of giant sequoia groves, by becoming educated advocates for "good fires" and tolerating their unpleasant smoke (versus the intense smoke from more severe fires), and by supporting conservation groups actively working in the region. Save the Redwoods League has been working with forest managers to study these groves and develop projects that can restore fire resilience across the Giant Sequoia Range, so that these mighty giants will be around for generations to come.