Wearing cowboy boots, a red tie, and his trademark ten-gallon hat, Walter E. Scott confidently strode into bars from Colorado to California, buying rounds of drinks for gullible listeners and attracting equally gullible investors with his tales of a secret gold mine in the heart of the famed Death Valley. Nicknamed “Sphinx of the American Desert” and “King of the Desert Mine” by news media, Scott and his flair for showmanship ultimately caught the attention of a Chicago millionaire who backed the myth of “Death Valley Scotty,” creating a desert Shangri-La and a national legend in the process. Still standing today in Grapevine Canyon within Death Valley National Park are the elaborate Spanish-style villa and ranch that tell a fantastic story of frontier romanticism, contrived riches, and real excess. Built in the 1920s and now listed in the National Register of Historic Places, the buildings and their arid setting were heavily damaged in 2015 by the strongest flash floods in recent memory. As efforts to repair the site and plan for its future continue, this historic desert landscape—at an elevation of 3,000 feet—is a reminder that the destructive effects of climate change on cultural and historical resources are far from limited to low-lying coastal areas.

History

Emblematic of frontier romanticism, the excesses of mining promotion in the early 1900s, and the conspicuous consumption that characterized the 1920s, this historic district traces its roots to the exploits of one man: Walter E. Scott. Known as Death Valley Scotty, this performer-turned-prospector was raised on a horse farm in Kentucky, which he left at age eleven to join his two brothers in Nevada. There he eventually worked as a water boy for a survey party in Death Valley, thus beginning his lifelong association with the area. Scott later spent twelve years with Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show, touring the United States and Europe from the age of sixteen.

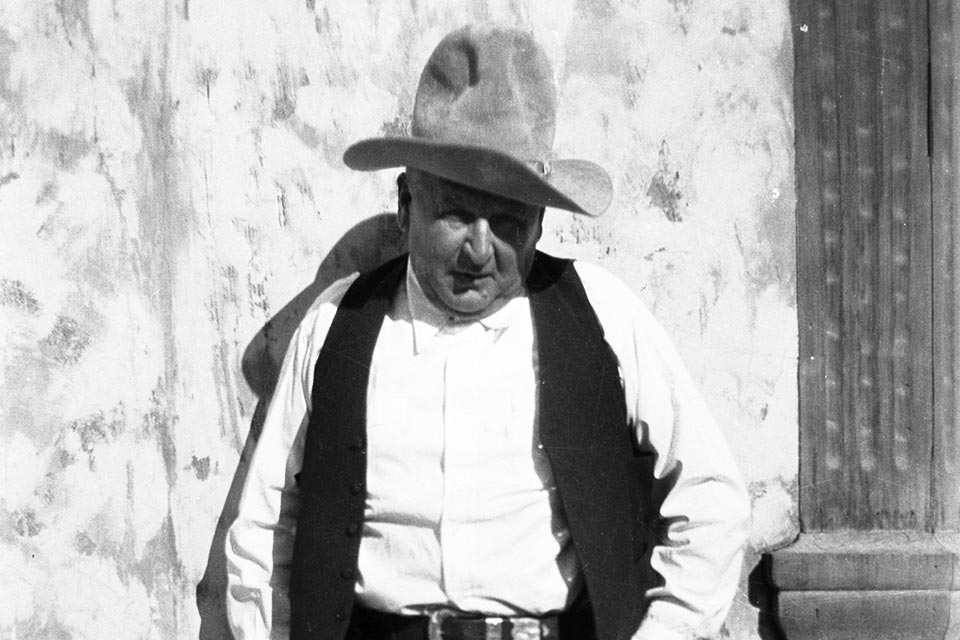

Legendary conman Walter E. Scott (a.k.a. Death Valley Scotty), ca. 1940s; photo courtesy Orange County Archives.

Legendary conman Walter E. Scott (a.k.a. Death Valley Scotty), ca. 1940s; photo courtesy Orange County Archives.

In 1902 Scott left Buffalo Bill’s employ and set his sights on gold-prospecting. He began seeking investors to fund a Death Valley gold mine to which he had laid claim. The profits from the extracted ore were to be split evenly, but over the next few years, hardly any gold was found. News of Scott’s gold mine, however, sparked the interest of New England mining magnate A.Y. Pearl and led to investors insisting that an engineer inspect the property. The gold mine turned out to be a ruse, and the discovery of Scott’s fraudulent schemes left him with just one backer. Chicago millionaire Albert Johnson, whom Scott met in 1904, would invest thousands of dollars in the gold mine over the next several years.

Seeking a return on his investment, Johnson endured a grueling trek through Death Valley to personally inspect the mine, ultimately discovering that he, too, had been swindled. Yet the desert expedition and Johnson’s love of the arid landscape surprisingly worked in Scott’s favor. Although of opposite personalities and from diverse backgrounds, the two men began a lifelong friendship, with Johnson continuing to fund Scott's endeavors in Death Valley. After repeated camping trips in the desert, Johnson and his wife, Bessie, decided to build a permanent winter home in Death Valley’s Grapevine Canyon, as well as a smaller retreat there for Scott.

"The Hall of Fame is going up. We're building a Castle that will last at least a thousand years. As long as there's men on earth, likely, these walls will stand here."Walter E. Scott

Construction began in 1922 at the location of the former Steininger ranch, where only spare structures still stood. Over the course of several years, architects Charles MacNeilledge and Martin de Dubovay, along with engineer Mat Roy Thompson, designed and built an elaborate complex of buildings with stucco-covered walls and red-tile roofs, including the primary “Castle” structures (with the Main House and Annex), the Hacienda, the five-story-high Chimes Tower (housing a tubular bell carillon), the Powerhouse, Cookhouse, Gas House, and a garage and stables. A network of subterranean concrete passageways was planned to connect the buildings, but only a few of the tunnels were ever built. Work on a large pear-shaped swimming pool was also advanced but left incomplete. A natural spring much higher in the canyon provided water to the estate and created its electricity, powering a Pelton Wheel (which extracts energy from moving water) that supplied batteries located in the tunnels. The estate was also furnished with a solar-powered water heater. While work on the Johnson’s villa was underway, a smaller, separate residential complex was built for Scott (and paid for by Johnson) just eight miles away.

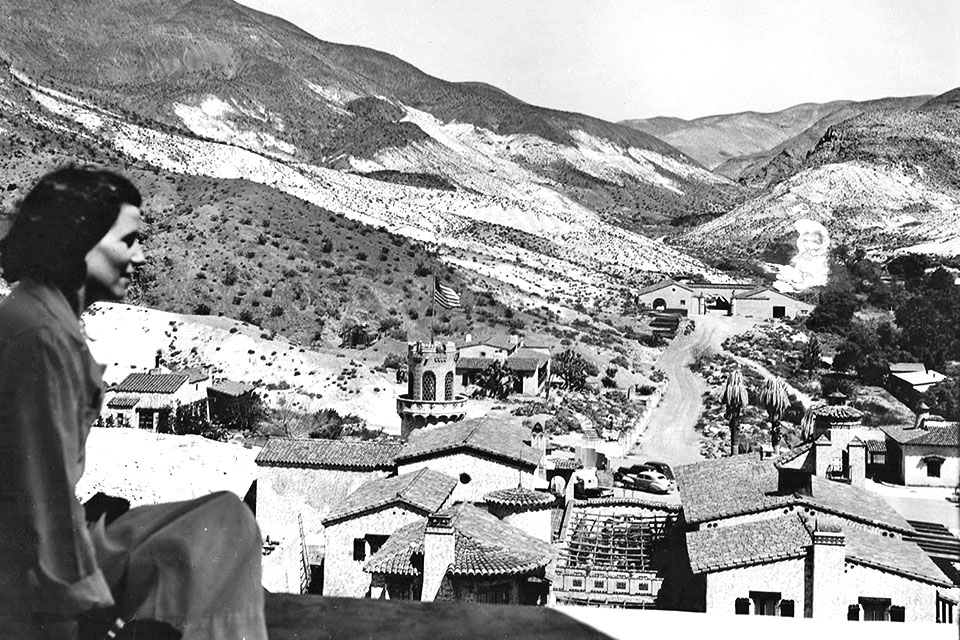

A view of Grapevine Canyon and the Scotty's Castle complex, ca. 1941; photo by Burton Frasher; Stephen H. Willard; L.P. Clarke - courtesy James Renault.

A view of Grapevine Canyon and the Scotty's Castle complex, ca. 1941; photo by Burton Frasher; Stephen H. Willard; L.P. Clarke - courtesy James Renault.

In 1929 landscape architect Dewey Kruckeberg (who would later serve as the superintendent of Park, Recreation and Community Services in Burbank, California) was hired to design the grounds of the Johnsons’ Death Valley retreat. The plan would incorporate a fig orchard, a vineyard, and many fruit trees, some of which were already extant but none of which survives today. A Tea Garden was also established, and other large trees and saguaro cacti were brought from as far away as Arizona. An artificial, rock-lined watercourse was built between the guest house and the garage, including two large pools and incorporating massive boulders and a petroglyph moved from elsewhere on the site. Two other such watercourses were planned but never completed. Olive and palm trees were planted throughout the grounds, the latter serving as the central feature of the entrance court east of the Main House but succumbing to the severe winter of 1938–1939. Red and orange jasper was brought from the nearby mountains and used to make terracing, while Native Americans fabricated more than 2,000 concrete posts on-site for the estate’s unusual concrete fences.

In a strange but perhaps fitting twist, Johnson would discover that the land on which he had built his estate did not belong to him—the result of an improper survey. Although the dispute was eventually resolved, construction was halted in 1931 in the midst of the Great Depression, and the ranch was never finished. By then, Johnson had lost much of his fortune and would eventually retire to Hollywood. But the myths surrounding the Death Valley oasis only grew, making it a popular tourist attraction. Thousands of visitors, including Hollywood celebrities and the news media, came to what was known as “Scotty’s Castle,” inspired by fantastic tales of Scotty and his mine. Johnson died in 1948, and the property was willed to the Gospel Foundation of California, a charitable organization that Mr. and Mrs. Johnson had founded. Scott was allowed to continue to live at the estate, which he did until his death in 1954. In 1970 the property was sold to the National Park Service (NPS).

Construction on the elaborate Scotty’s Castle began in 1922; photo by Chen Jack, 2011.

Construction on the elaborate Scotty’s Castle began in 1922; photo by Chen Jack, 2011.

Located along the northern edge of Death Valley National Park amid Grapevine Canyon, the property totals some 1,500 acres and is divided into the Upper and Lower Ranches, just miles apart. The Upper Ranch hosts the grander buildings collectively known as “Scotty’s Castle,” where the water feature, a swimming pool, rock gardens, paved walkways, and a relatively lush, open landscape enliven the canyon floor. The irregular plot contains the estate’s original 1920s structures and the Cookhouse, which was partially rebuilt. A narrow, winding lane meanders from the Chimes Tower and leads to Scott’s grave, perched on the hillside at Windy Point. As the valley is the driest place in North America, the landscape still relies heavily on the natural springs of Grapevine Canyon, highlighting the strategic use of water in the remote desert environment.

Extant landscape features at the Lower Ranch include a water trough for passersby, a reservoir, a natural spring terrace, and agricultural fields. Built with redwood walls and shingle roofs, the ranch buildings, which include a blacksmith’s shop, corrals and agricultural buildings, are smaller and purely utilitarian. The spatial layout and circulation of the complex closely resembles that of a Spanish village. Together, the Lower Ranch and Scotty's Castle (at the Upper Ranch) comprise the Death Valley Scotty Historic District, listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1978.

Threat

According to the National Park Service’s model-based projections on climate change, Death Valley is especially vulnerable to flooding given its already arid landscape. Changes in precipitation patterns coupled with increasing temperatures will lead to more frequent and violent weather events. These conditions will also likely result in the extirpation of several species from Grapevine Canyon. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), temperatures could increase as much as four to seven degrees Fahrenheit by the end of this century. Although predictions are not definitive, extreme weather events have already begun to adversely affect the Death Valley Scotty Historic District and its cultural and natural resources.

On October 18, 2015, rain and hail pummeled the area, amounting to 2.7 inches of precipitation—equivalent to more than half the site’s annual rainfall—in the span of just five hours. This historic deluge triggered a flash flood carrying mud, boulders, and trees, moving at a rate of 2,300 cubic feet per second, which breached the interior of two of the estate’s historic structures and caused significant damage within the historic district. Much of the vegetation and natural features, including the pool, were affected, with parts of the landscape scoured to a depth of eight feet, while other areas were buried in several feet of mud and rocks. The historic Hacienda escaped the worst of the flooding but was left in mud two feet deep. A museum collection containing more than 139,000 artifacts and archival material was threatened by exposure to humidity. The damage to structures, garden features, main access roads, and utilities in and adjacent to the historic district is estimated at $47 million. What is more, scientists predict that even larger floods than this one will surely occur.

What You Can Do to Help

The NPS and the Federal Highway Administration are working to reconstruct 7.6 miles of Scotty’s Castle Road that was washed away during the flood. The historic landscape and structures are also undergoing rehabilitation, and the status of the work can be viewed here. The NPS is also designing flood-control structures, including berms, floodwalls, and shallow concrete-lined canals. Unfortunately, the addition of these structures to the historic district will have an adverse impact on the integrity of the resources, but if preventive measures are not taken, the Upper and Lower Ranches will be at risk of flood damage in the future.

The public can support these measures by donating to the Death Valley Conservancy’s Friends of Scotty’s Castle Fund, either by mail or via PayPal.