Introduction

A Message from Jonathan B. Jarvis for Landslide 2019

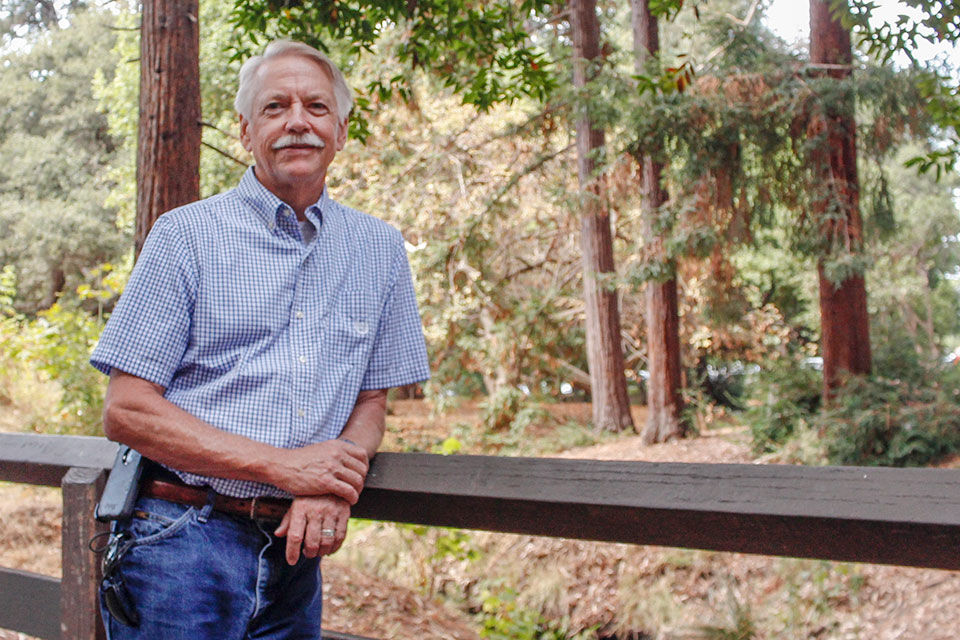

Jonathan B. Jarvis, former director of the National Park Service.

Jonathan B. Jarvis, former director of the National Park Service.

At a National Park Service (NPS) meeting on climate change I hosted more than a decade ago, attended by climate scientists and specialists in natural and cultural resources, the cultural specialist explained how one could survey and document an at-risk, coastal cultural resource and then, if it were truly doomed by a rising sea, let it go. The biologist retorted, “At least you have a process by which you can say good-bye.” Based on the current trajectory of climate change and the lack of political will to make hard decisions, we are going to be saying a lot of good-byes. As the director of the NPS from 2009 to 2017, and having served its stewardship mission for 40 years, I was often vocal in stating that climate change is the greatest threat to the integrity of our national park resources in the more than 100-year history of the organization. The list of endangered cultural landscapes in this important Landslide report could easily be expanded. I watched as floods from climate change wiped out a 100-year-old campground in Mt. Rainier National Park, and I helped the Ahtna people of Alaska re-bury human remains washed out of melting permafrost in Wrangell-St. Elias. The sacred sites of Puʻukohola Heiau, the Blackwater swamps of Harriet Tubman’s midnight escapes, and the barrier islands of Cape Hatteras are not replaceable. But within those landscapes there are lessons, if only we learn them.

Humans have been modifying their environments for a very long time, and our work is captured in the cultural landscapes we leave behind. Researchers study the remnants of our ancient lives, our trash heaps, plantings, fire pits, water works, burials, and our astonishing ability to move massive amounts of dirt and stone. From that science, we try to understand the people, their traditions and cultures, and how, over time, they responded to change. Many of these landscapes were abandoned at some point in their history. Research suggests that sites occupied for centuries were deserted due to violent conflict with neighbors, crop failures, natural disasters, local resource exhaustion, and—yes—climate change. Harvard professor Dr. Jason Ur, who studies the ancient civilizations of Mesopotamia, states, “When we excavate the remains of past civilizations, we rarely find any evidence that they made any attempts to adapt in the face of a changing climate. I view this inflexibility as the real reason for collapse.”

But back then, there was always somewhere else to go—a greener pasture, a wilderness (or another civilization) to be conquered, another resource to be exploited for human use. Now that climate change is affecting the entire planet, there is nowhere else to go. Some in the scientific community believe we have begun a new era, the Anthropocene, in which humans are now modifying the environment at a global scale, changing the trajectory of the planet in a way that is potentially as catastrophic as the Permian-Triassic Extinction some 250 million years ago. In the Anthropocene, the entire planet is a cultural landscape, but not one we can leave behind, at least not with current technology. Mars is a long way off; not very hospitable and Elon Musk’s spaceship is kind of small.

Embedded in the study of cultural landscapes and the warnings of climate change are lessons from those civilizations that learned to live in harmony with their environment and those that did not. Those lessons are relevant to how we, as humans, can learn to live in harmony with our planet. Rich Sorkin, co-founder of Jupiter Intelligence, recently commented regarding climate change: "We live in a world designed for an environment that no longer exists." I believe that we have the analytical capability to redesign at a landscape scale for maximum resilience to climate change.

Learning to manage at the landscape scale, with parks or equivalent protected areas linked to corridors and integrated with communities, transportation systems, watersheds, agriculture, and sustainable economies is a critical component for adapting to a rapidly changing climate. While we have powerful analytical tools to envision or even design large landscape connectivity, we must also have the political and public policy tools to achieve the “governance” required for it to be sustained. Using the same analytical power of geospatial data and software now used to reveal ancient civilizations, coupled with predictive models on the effects of climate change (sea-level rise, changes in precipitation, hurricane frequency and intensity, wildfires, etc.), large landscapes can be redesigned to provide multiple benefits to both humans and nature. The current climate crisis requires “all hands on-deck,” and the cultural landscape community has important lessons to share in a unified vision for conservation, in addition to sounding the alarm. Alarms, after all, have been ringing now for at least a decade, and only a few have awoken.

The last chapter of my recent book, The Future of Conservation in America: A Chart for Rough Water, co-authored with Dr. Gary Machlis, is titled “Resilience.” We say in part:

We have confidence that the unified vision of conservation will result in significant progress over the long term. The coming together of nature conservation, historical preservation, ecosystem services, environmental justice and civil rights, sustainability, public health, and science communities is overdue, but when fully accomplished will reap significant reward. As these interests increasingly practice the skills of collaboration, and gain experience in working closely together in more common cause, they will find their collective “voice” to be powerful, influential, and effective. (p. 82)

Without too much hyperbole, the survival of the human race depends on figuring out how to adapt to a changing environment. Our ability to manipulate the environment for our benefit is well documented on the land. By better understanding the landscapes left by our ancestors, we can apply those lessons at a global scale using the restorative power of nature. Even within dense urban communities, large landscapes can become highly resilient to climate change. As you read through TCLF’s annual Landslide and lament the loss of irreplaceable cultural and historical sites, get angry and then get busy. The planet needs you.

Jonathan B. Jarvis was the eighteenth director of the National Park Service. He is currently the executive director of the Institute for Parks, People and Biodiversity at the University of California, Berkeley.