Set along the water’s edge in the historic maritime town of Newport, Rhode Island, the Easton’s Point neighborhood boasts one of the highest concentrations of Colonial-era homes in the United States. Located north of the harbor and fronting Narragansett Bay, the enclave of richly articulated eighteenth-century streetscapes is part of the Newport National Historic Landmark District, established in 1968. While the low-lying area and its unrivalled collection of historic structures have never been immune to the forces of nature, the frequent and severe flooding of recent decades has brought the neighborhood and its stewards to a crossroads, making Easton’s Point emblematic of the challenges—and hard choices—that many culturally rich coastal areas will face in the wake of a changing climate.

History

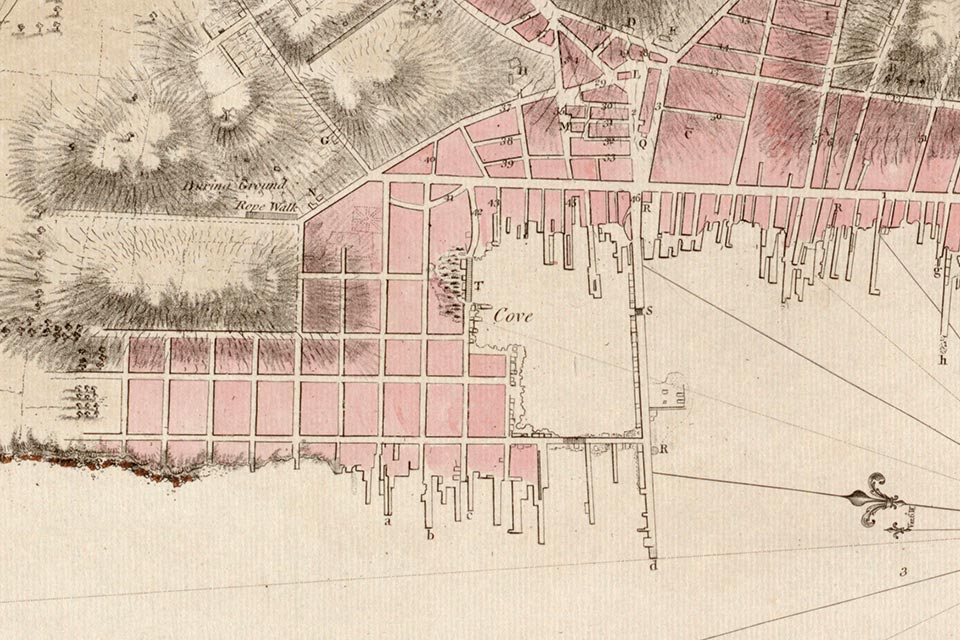

Easton’s Point (known today as ‘The Point’) is named for Nicholas Easton, one of a small band of settlers who traveled south from Portsmouth (then called Pocasset) on Aquidneck Island to found the Town of Newport in April 1639. The Narragansett people had hunted, fished, and cultivated the land of Aquidneck Island for centuries, if not millennia (Aquidneck is derived from the Narragansett name for the island, aquidnet), making their homes on the nearby mainland. Soon after Easton arrived, he began farming the land that he would eventually deed to the Society of Friends in 1674 as part of his last will and testament. After his widow, Ann Bull Easton, gave additional acreage to the Quakers in 1706, they subdivided and platted the area in 1725, selling the lots to merchants, tradesmen, and artisans who made their homes and plied their trades in what became a lively enclave. The neighborhood’s three north-south streets, Washington Street (originally called First Street), Second, and Third Streets, run parallel to the shoreline and are crossed at right angles by approximately a dozen shorter east-west streets named for tree varieties—Pine, Cherry, Willow, etc. The gridded layout produced lots of roughly equal size in keeping with the Quaker tradition.

Plan of the Town of Newport in the province of Rhode Island, with detail of Easton’s Point; by Joseph F. W. Des Barres, 1781; courtesy Norman B. Leventhal Map Center, Boston Public Library.

Plan of the Town of Newport in the province of Rhode Island, with detail of Easton’s Point; by Joseph F. W. Des Barres, 1781; courtesy Norman B. Leventhal Map Center, Boston Public Library.

Closest to the shoreline, Washington Street nevertheless became the preferred location for the grand Georgian homes of successful merchants, while smaller dwellings, shops, and outbuildings were constructed in a compact grid of perpendicular streets, along with gardens, fences, and pathways. The neighborhood’s growth reflected Newport’s status as one of the most important colonial seaports and urban centers of the time. By 1715 Newport boasted more than a dozen shipyards, and by 1761 it had joined the ranks of Boston, New York, Charleston, and Philadelphia as one of the five largest port cities in the colonies, with nearly 900 residences and 440 warehouses and storage buildings. No small measure of Newport’s prosperity had come from involvement in the slave-trade. By the mid-eighteenth century, approximately one-third of Newport’s families owned slaves, and fully ten percent of the city’s population was of African descent.

The mid-eighteenth century has been described as a Golden Age for Newport and, by extension, for Easton’s Point. Records show that some two-thirds of the residential buildings in the neighborhood were two stories high, an indication of its prosperity. Here, for example, the houses and workshops of the Townsends and the Goddards, two well-known Quaker families whose fine furniture was exported to destinations throughout the colonies and the West Indies, were located next to the wharves that guaranteed easy access to transport.

But Like Newport itself, Easton’s Point would face a period of marked decline in the wake of the Revolutionary War, when, from December 1776 to October 1779, British troops occupied the town. During this three-year period, some 480 buildings were destroyed—many only to supply firewood. By war’s end, the population of what had been the largest settlement in Rhode Island was more than cut in half. The recovery would be painfully slow, but Newport would thrive again in the 1830s, not as a commercial center, but rather as a summer resort community. The nature of Newport’s recovery would, however, prove a key factor in the preservation of much of its historic fabric. As it became the preferred summer retreat of well-to-do nearby urbanites, Newport retained much of its historic character and avoided the wholesale razing of large swaths of neighborhoods that accompanied rapid industrial growth in other East Coast cities. A population that numbered approximately 8,000 in 1840 had more than doubled to 20,000 by 1885, as the elite of America’s Gilded Age flocked to Newport, driving a boom in the construction of both year-round and vacation homes.

Easton’s Point continued to thrive at the turn of the twentieth century, although the days when its wharves teemed with commercial goods were long gone. The presence of naval facilities in Narragansett Bay would, however, continue to buoy the neighborhood, filling the historic homes with a ready supply of renters. The Navy had established a permanent presence on nearby Goat Island in 1869, when it opened the Naval Torpedo Station there, which, during World War II employed more than 13,000. Tracing its roots to 1883, the U.S. Naval Training Station was also a boon to the local economy. But in 1973 several naval facilities moved to Norfolk, Virginia, taking nearly 20,000 jobs with them. Many of the homes in Easton’s Point, which had languished over the years, were left vacant, and several were condemned.

From 1966 to 1969 the Newport Bridge (now the Claiborne Pell Newport Bridge) was built to connect Newport to Conanicut Island, cleaving the northern portion of Easton’s Point in the process. Other projects were completed under the banner of urban renewal, including the construction of America’s Cup Avenue and Market Square, the former a four-lane highway that sliced through the Easton’s Point area. Spurred in part by these changes to the vernacular landscape, the late tobacco heiress and philanthropist Doris Duke founded the Newport Restoration Foundation (NRF) in 1968 with the aim of preserving Newport’s historic structures and neighborhoods. Throughout its history, the NRF has restored more than 80 structures in Newport and now owns some 27 of the historic homes in Easton’s Point, some of which were transplanted from elsewhere in Newport. It was also in the 1960s that “Operation Clapboard” got underway in Easton’s Point, a grassroots movement to identify historic homes in need of repair and match them with owners committed to their restoration.

Homes in the Easton’s Point neighborhood are typically located close to the street and sheathed with clapboard siding; photo courtesy Discover Newport, 2005.

Homes in the Easton’s Point neighborhood are typically located close to the street and sheathed with clapboard siding; photo courtesy Discover Newport, 2005.

Today, some 400 pre-Revolutionary War homes still stand in Newport, with approximately 100 of them located within Easton’s Point. Homes there are predominately sheathed with clapboard siding and are sited in close proximity to each other and the street, creating a consistent signature streetscape. The thin spit of land that once extended south from the neighborhood into Newport Harbor, forming a cove and giving the area its name, is no longer readily discernable. The cove was once encapsulated by the Long Wharf, which, beginning in 1702, ran east from Market Square to reach “The Point.” The homes that lined Bridge Street, to the north, were then waterfront properties, many with docks. To the south was Marsh Street, whose name aptly described the swampy nature of the area that it crossed. But by 1907 the cove had been completely in-filled. Situated along the Bay to the north, between Battery and Pine Streets, is Battery Park, originally the site of the so-called North Battery, an artillery installation that was still incomplete when the British occupied the town. British troops enlarged the battery but destroyed it in 1779 when they evacuated. By 1798 the battery had been rebuilt and was called Fort Green. It remained active until circa 1811, becoming a city-owned park in 1891, with the original seawall still intact.

Threat

Occupying one of the lowest elevations in Newport, Easton’s Point is no stranger to flooding, which is caused by two factors. During severe weather events, storm surge can inundate the neighborhood, taking advantage of its drainage system as a natural point of entry. Another type of flooding occurs during high tides when tide gates are closed to prevent tidal waters from entering the neighborhood. Stormwater can then become trapped behind the gates and can backflow into the storm-drainage system.

As the area of impermeable surfaces—paved roads, lots, and other surfaces—uphill from Easton’s Point increases, so, too, does the overall volume of water that must pass through the neighborhood and its drainage infrastructure. It has been estimated that one inch of precipitation causes as much as 860,000 gallons of water to discharge through the Washington Street outfall alone. When such precipitation coincides with high tide, the two flows—tidal inflow and drainage outflow—meet in the drainage system, causing severe flooding at its low points, often around Second and Third Streets.

The effects of storm surge are exacerbated by rising sea levels in the wake of global warming—an example of climate change acting as a threat multiplier. When combined with the effects of subsidence and tidal wash, the threats from rising sea level, greater storm surge, and increasing precipitation mean that Easton’s Point and its historic structures are likely to suffer significant losses. The City of Newport recently commissioned a special report on drainage and flooding issues in the southernmost section of Easton’s Point. The report developed short- and long-term solutions for the low-lying areas subject to tidal flooding during exceptionally high tides. As a result, the city has installed new tide gates on local storm drains to help manage near-term flooding.

What You Can Do to Help

In April 2016 the NRF convened a four-day conference titled Keeping History above Water, during which presenters offered a multi-disciplinary perspective on the various risks to historic coastal communities from sea-level rise and climate change. One takeaway from the Newport conference is that conventional methods for protecting homes against flooding are sometimes incompatible with the mandates and aims of historic districts, which seek to maintain the visual and spatial qualities of the neighborhood—a challenge that the city, and many others, no doubt, will have to overcome. Subsequent conferences underwritten by the NRF were held in Annapolis, Maryland (2017), Palo Alto, California (2018), and St. Augustine, Florida (2019).

Additionally, the City of Newport’s Historic District Commission has established a Sea Level Rise Task Force, which is currently compiling case-studies from historically significant communities along the Eastern Seaboard that are experiencing an increase in severe storms and storm surge. The city will continue to work closely with the NRF and other community stakeholders, as well as local, state, and federal agencies, to establish guidelines for elevating historic buildings and implementing measures to help protect Newport and its resources against hurricanes.

Support the work of the NRF and help the historic Easton’s Point neighborhood meet the many complex challenges that it faces.