Twin Cities' Landscape Legacy

Setting the Geological Stage

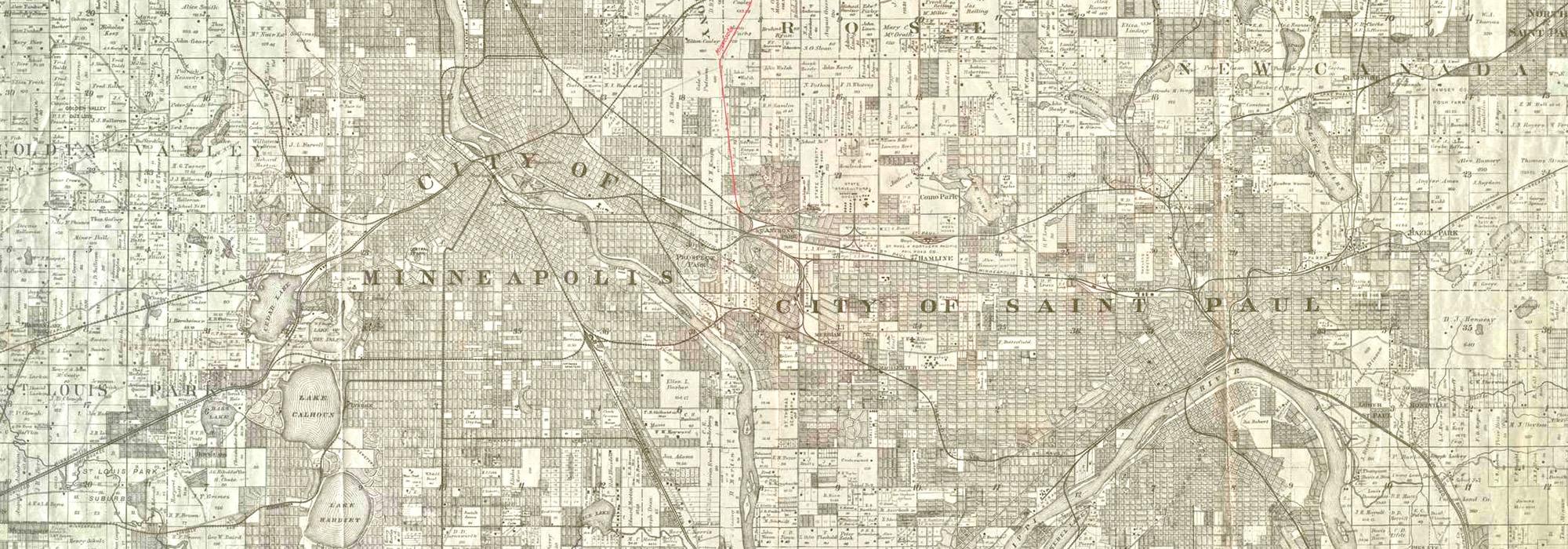

Minneapolis and St. Paul owe their lakes, rivers, and landforms to the glaciers that came and went during a series of ice ages thousands of years ago. Melting glaciers produced the giant Lake Agassiz, which stretched across part of northern Minnesota, adjacent states, and Canada.

The glaciers left behind a layer of “drift”—earth, stone, and other materials—which rests on a ledge of Platteville limestone, exposed in many places along the Mississippi River gorge. Ranging from gray to tan in color with distinct bedding planes, the limestone was quarried to build Fort Snelling in the 1820s and structures in parks during the Great Depression.

Neither Platteville limestone nor the layer of Saint Peter sandstone below it could resist the erosive force of the Mississippi River. Some 12,000 years ago, Saint Anthony Falls was first located near what is now downtown St. Paul. As the rushing water wore down the falls’ structure, the crest migrated upstream.

The region’s vegetation is influenced by this geography, as well as by the Twin Cities’ location midway between the north pole and the equator. A monument marking the forty-fifth parallel was installed near Theodore Wirth Park’s north entrance in 1917.

Occupying Sacred Ground

For thousands of years, the region’s forests and prairies were occupied by Native peoples for whom the Mississippi River and its tributaries provided a natural transportation system that facilitated trading and provided food. The confluence of the Mississippi and Minnesota Rivers is known as Bdote to Dakota people and many consider it a sacred place of creation. The Dakota and the Ojibwe were the main groups living in the area when European explorers and missionaries began arriving in the seventeenth century. Next came the fur traders, who established trading posts across the region.

Ownership of the land by Native peoples was largely ignored by the European countries that set stakes in the area, starting with France, which claimed the entire Mississippi River Valley in 1682. Spain gained title to the land west of the Mississippi in 1762. It was ceded back to France in 1800, then sold to the United States in 1803, a transaction known as the Louisiana Purchase.

In 1805, an “agreement” of dubious legality with Dakota leaders for land at Bdote enabled the United States to establish Fort Snelling on a dramatic bluff overlooking the Mississippi River in 1819. The fort was one of a series of military posts the fledgling nation established to secure its new territory. Land between the Saint Croix and Mississippi Rivers was opened to Euro-American settlement by treaties ratified in 1837. On the west bank of the Mississippi, land outside of the military reservation remained Dakota territory until the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux in 1851, so other settlement was prohibited—although several squatters ignored this restriction. Still, the state’s population of Native peoples probably exceeded that of Euro-Americans until after 1850.

City Shaping and Building

Following the 1837 treaties, steamboats delivered a steady stream of pioneers to the head of navigation on the Mississippi, a community that took its name from the chapel established there by a Roman Catholic priest in 1841. St. Paul was chartered as a town in 1849 and became the state capital when Minnesota achieved statehood in 1858.

During the same period, a village grew upstream on the east bank of Saint Anthony Falls, a power source that would make Minneapolis the flour-milling capital of the world within a few short decades. When the first plat was filed for the town of Saint Anthony in 1849, the population stood at 248, and the village became incorporated in 1854. Settlement on the river’s west bank got a later start, remaining part of the Fort Snelling military reservation until the reservation’s size was reduced in 1852. Houses and claim shanties quickly appeared in the nascent community, christened Minneapolis.

The nationwide Panic of 1857, the U.S. Dakota War of 1862, and the Civil War slowed the momentum of development, but new arrivals continued to appear in the area. By 1865, the population was around 13,000 in St. Paul, 2,600 in Minneapolis, and 3,500 in Saint Anthony. And then the floodgates opened. When Minneapolis absorbed Saint Anthony in 1872, their combined population was over 18,000 and gaining on Saint Paul. In 1880, Minneapolis claimed 46,887 residents to Saint Paul’s 41,473, and it would continue to lead its eastern sibling going forward. Within only five years, the population surged to 129,200 in Minneapolis and 111,397 in St. Paul. This phenomenal growth caused rapid environmental, social, and economic changes.

Provident Parks

While parks were not initially a priority for the city governments, farsighted civic leaders realized that the opportunity for establishing parks would be lost if they waited too long. Early efforts were modest and private citizens donated land to St. Paul for its first parks—Rice, Irvine, and Smith (now known as Mears)—in 1849. Businessman Edward Murphy gave Minneapolis 3.33 acres from an 80-acre plat for its first park in 1857, but the site remained little more than a cow pasture for years.

The push for parks gained little momentum until February 1872, when Horace William Shaler Cleveland delivered lectures in Minneapolis and St. Paul about a plan for an ambitious park system encompassing both cities. Cleveland recommended “an extended system of boulevards, or ornamental avenues, rather than a series of detached open areas or public squares.” This was not only an aesthetic consideration. Cleveland had lost many possessions in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 and saw parkways as an effective firebreak in built-up urban areas. In addition, Cleveland stressed the sanitary benefits derived from parkways at a time when cholera, typhus, and other diseases routinely plagued cities. Parkways could save land from unhealthy uses and be the lungs of the city. Parks also brought economic benefits, raising the value of nearby private land. Cleveland advised that a holistic strategy for the park system be prepared at the outset, with implementation coming in phases as funding became available.

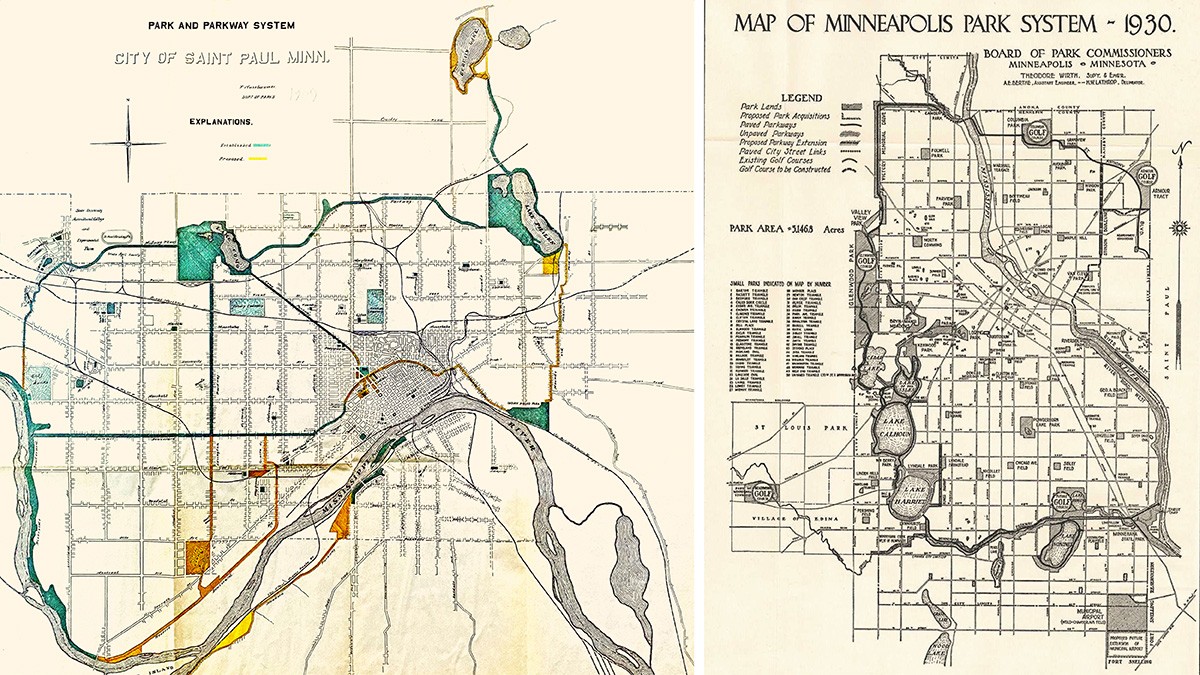

Two months after Cleveland’s lecture, St. Paul hired him to outline a comprehensive park plan for the city. Although a national economic depression in 1873 thwarted his ambitious proposal, the city did acquire land for Como Park that year. This was the start and heart of the city’s ultimate system, a framework known as the Grand Round.

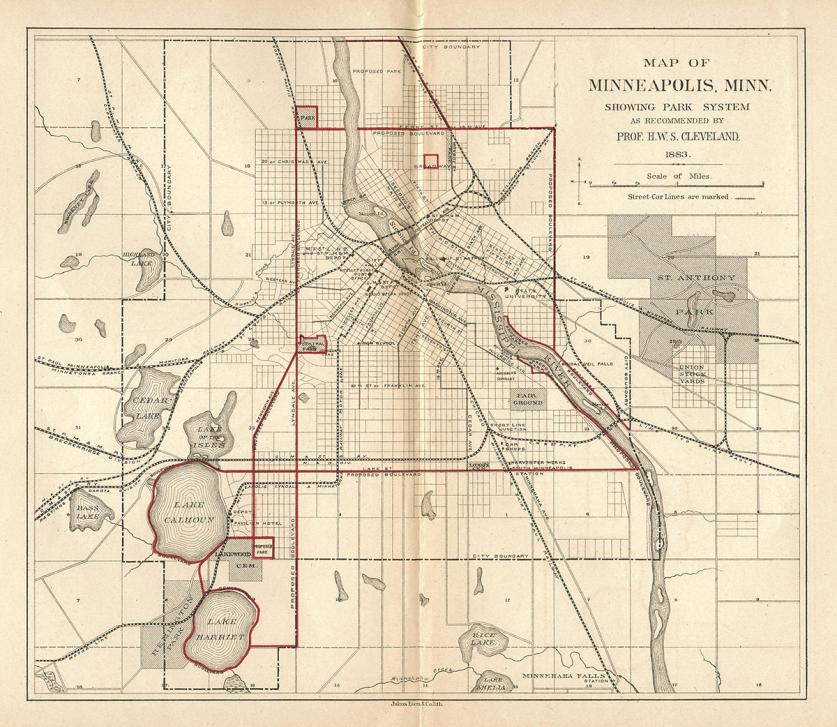

In Minneapolis park proponents circumvented local resistance and convinced the state legislature to authorize a referendum that established a board of park commissioners separate from city government. One of the first actions of the new board was to retain Cleveland, who presented “Suggestions for a System of Parks and Parkways” at a meeting in June 1883. He encouraged the board to acquire exceptional natural features and link them with scenic boulevards: Hennepin and Lyndale Avenues from Lakes Harriet and Calhoun (now Bde Maka Ska) to the prominent knoll that became Farview Park; Twenty-sixth Avenue North to the Mississippi River, then along the river to Minnehaha Falls; and Lake Street linking the river to the lakes. As the city grew—and Hennepin, Lyndale, and Lake became too busy to be parkways—the vision expanded as well.

By 1891, the framework of parks and parkways included Minnehaha Parkway and Glenwood (later Theodore Wirth) Park and was christened the Grand Rounds. Much of this work was carried out under the direction of William Morse Berry, the first full-time superintendent, with collaboration from prominent board members including businessman Charles Loring.

St. Paul established a board of park commissioners after state legislation in February 1887 authorized the city to issue bonds for improving and purchasing parklands. The new board hired Cleveland to prepare plans for improving Como Park, one of the four anchors to the planned system along with Lake Phalen to the east, Indian Mounds Park to the southeast, and a boulevard along the Mississippi River, originally known as Riverside Park. After several delays and the Panic of 1893, the board eventually cobbled together parcels for Mississippi River Boulevard and other parks through purchase and generous benefactors, such city health commissioner Justus Ohage, who donated Harriet Island for park use in 1900.

The board faced other challenges in implementing the preliminary plan for the city parkway system that Cleveland outlined in July 1887 including the failure to carry Summit Avenue across the river to Thirty-fourth Street in Minneapolis, which Cleveland proposed as a link to the Chain of Lakes. His hope for another intracity connection between the State Capitol in St. Paul and the University of Minnesota campus in Minneapolis was also not completed as envisioned, although significant sections (Como Avenue and Midway Parkway) were created.

The Turn of Two Centuries

Some St. Paulites considered Cleveland a “Minneapolis man” and his involvement waned when Frederick Nussbaumer was promoted to park superintendent in 1891, after four years as a gardener in Como Park. He worked closely with Joseph Wheelock, a patron, visionary, and promoter, who became a park commissioner and board president in 1893. As editor of what is now the St. Paul Pioneer Press, Wheelock made park planning and development a regular feature of city news. After his death in 1906, the parkway connecting Lakes Como and Phalen was named in his honor.

Nussbaumer, who served as superintendent until 1922, was encouraged by prominent citizens, including businessman Alpheus Stickney, to expand the city’s network of parks and boulevards in the early twentieth century. For Stickney, St. Paul’s most important natural amenity was the Mississippi River and adjacent land. He urged the city to acquire more of the river bluffs before they were ruined by commercial interests and pragmatically sought to repurpose existing roads as boulevards to link parks.

The twentieth century brought new leadership to Minneapolis parks with the arrival of Theodore Wirth as superintendent in 1906. His mandate included completing the Grand Rounds and establishing and upgrading neighborhood parks to meet increasing demand for recreation in a rapidly expanding urban population. After retiring as superintendent in 1935, he continued to influence park development, writing a definitive park history published in 1945.

Parks in Minneapolis and St. Paul benefitted from federal relief programs in the 1930s, which fostered a compatible rustic aesthetic. After World War II, the design of recreation centers and other park amenities became more modern and utilitarian as the systems struggled to maintain their expansive holdings and compete with newer suburban facilities.

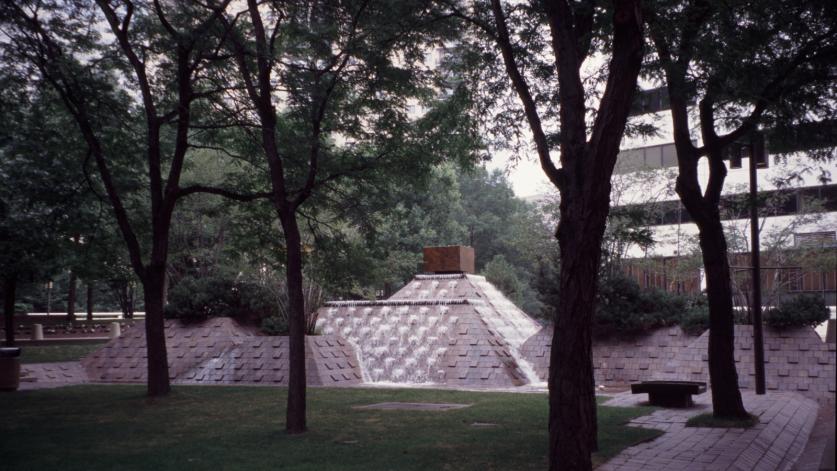

The late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries have witnessed a renaissance of the urban areas and their park systems. In Minneapolis, the transformation was triggered in the mid-1950s when General Mills announced plans to move its headquarters out of downtown to a new suburban campus. The Pillsbury Company considered following suit but civic and business leaders convinced them to remain. The public and private sectors collaborated on innovative planning concepts to resuscitate the down-in-its-luck downtown. The Nicollet Avenue retail corridor was transformed by 1967 into one of the country’s earliest pedestrian malls with guidance from Barton Aschman and an innovative design by Lawrence Halprin and Associates. Nicollet Mall’s popularity led to a four-block extension with a public space, Peavey Plaza, completed in 1975 and rehabilitated in 2019, as an elegant front yard for the new Orchestra Hall.

M. Paul Friedberg + Partners drew up plans for both the plaza and the Loring Greenway, a linear neighborhood park between the mall and Loring (originally Central) Park. On the other side of Loring Park, the Walker Art Center and the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board joined forces to create a sculpture garden. In neighborhoods, historic landscapes and houses inspired rehabilitations like Milwaukee Avenue in Minneapolis and Irvine Park in St. Paul, which were listed in the National Register in the early 1970s.

St. Paul’s first urban renewal campaign began in the mid-1940s when the city and state cleared a broad swath of deteriorating buildings surrounding the Minnesota capitol and installed a monumental mall more befitting Cass Gilbert’s Beaux Arts edifice. The private sector played a bigger role when another phase of urban renewal was launched in the 1960s, the Capital Centre project, which conducted wholesale demolition on a dozen blocks in the downtown core. The new buildings, landscapes, and other features that appeared on those sites unabashedly embraced the aesthetics and idealism of the Modern era.

Both cities installed second-level skyway systems, a mixed blessing. While allowing office workers and shoppers the freedom to go coatless from building to building regardless of the season, the skyways drew people and retail off the street level. This has been somewhat ameliorated by the development of new downtown housing and the conversion of adjacent warehouse districts into lively neighborhoods with housing, commercial and cultural destinations.

In the first decades of the twenty-first century, historic public open spaces like Rice Park have been revitalized and new parks have been created that make good on planning proposals envisioned more than a century earlier (Twenty-sixth Avenue Overlook), heal the legacy of a freeway-damaged neighborhood (Rondo Commemorative Plaza), bring name-brand art to a neighborhood gathering spaces (Western Sculpture Park), and entice new development rich in public amenities (The Commons). Both cities have reclaimed their Mississippi waterfronts; Harriet Island has been upgraded and expanded and Minneapolis’s downtown riverbanks have been bestowed with a post-industrial ribbon of public spaces that celebrate the area’s natural and cultural history.

As the Twin Cities continue to evolve, efforts are underway to make its parks and landscapes more culturally inclusive and socially relevant to both the Native peoples who originally inhabited the land and more recent, historically underserved populations who live in surrounding neighborhoods. Evolving public spaces like George Floyd Square, site of memorial and protest, add to the diversity of the region and provide communities with meaningful outlets for expression within the public realm.

“I would have the City itself a work of art,” Cleveland exclaimed in 1883. Today, a greater typological diversity and distribution of parks and public spaces are expanding the audience they can serve, the stories they can tell, and how, through design and meaningful public engagement they can heal damaged ecological systems and cultural lifeways.