Eero Saarinen asked Dan Kiley to act as a consultant on the design for the new campus for the United States Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, CO. Begun in 1954, the architecture firm of Skidmore, Owings and Merrill (SOM) was selected to take the lead on the project with architect Walter Netsch at the helm. When Kiley joined the team, the firm had already created a preliminary master plan and layout for the site. According to Kiley “…it was no accident that my office was selected to consult…I was at that point establishing a reputation as a landscape architect who rejected traditional compositional methods, instead seeking organic order and balance in concert with architectural elements. We pushed to reveal a sense of movement on the land, as well as to connect outwards to the essence and spirit of the site.”

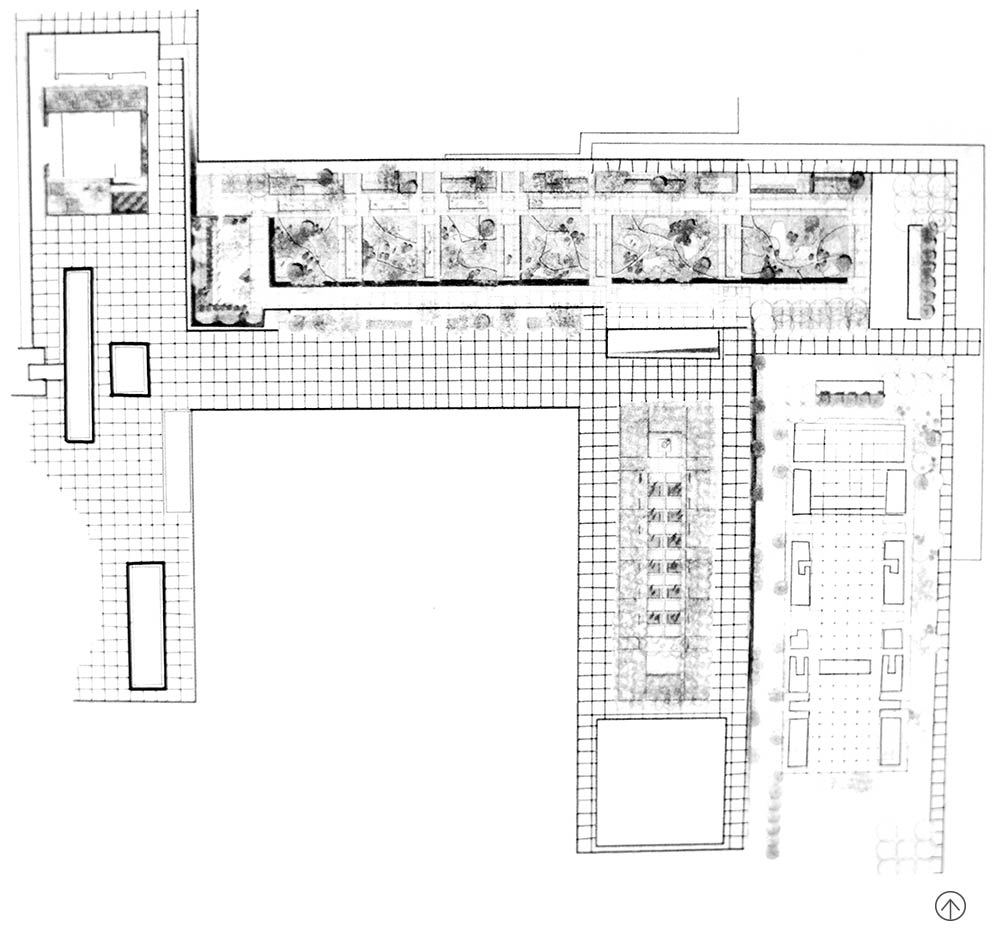

The setting for the campus, 18,455 acres at the foot of the Rocky Mountains’ Rampart Range, provided a stunning backdrop to the team’s Modernist design. The site was nested within a natural landscape of valleys and plateaus vegetated with stands of evergreen, fir, juniper, spruce and pine stretching out from the mountain’s base. A ten-minute walking radius drove the campus layout, with classes, athletics, and meals on a north-south axis and special events and the chapel running east-west. Kiley’s plan centered on the core of the campus, the Academy’s twenty-seven-acre Cadet Area, which also acts as the public face of the campus. SOM’s master plan established the buildings and public spaces within the Cadet Area on a 28-foot grid. In fact, Netsch used seven foot increments (or multiples thereof) to structure both the architecture and the campus plan, from window size to the scale of the plazas. Within the space, the architects used a series of retaining walls to create a constructed mesa adjacent to a small hillock. This natural backdrop was integral to the campus design. In Kiley’s words: “We all felt somehow that reference to this juxtaposition was an essential principle of the scheme. To me, the presence of that hill was so essential that I fought the Air Force Construction Agency who were attempting to shave it down to the regulation profile of 2.5:1.”

.jpg) The focal feature of Kiley’s design was a central parade ground containing a 700-foot-long gridded series of grass panels and fountains set along a north-south axis, which he called the “Air Garden.”Kiley intentionally offset his grid so that visitors to the garden would be unable to traverse the space in a straight line, counter to the structured rigidity of the cadet’s daily life. At one end of the Air Garden is a flagpole and at the other a memorial and u-shaped pool containing five water jets. Drawing the eye down the length of the landscape is a series of rectangular clipped hedges of American holly, and on either side of the watercourse, a grove of honey locusts is densely planted fourteen feet on center, four trees wide.

The focal feature of Kiley’s design was a central parade ground containing a 700-foot-long gridded series of grass panels and fountains set along a north-south axis, which he called the “Air Garden.”Kiley intentionally offset his grid so that visitors to the garden would be unable to traverse the space in a straight line, counter to the structured rigidity of the cadet’s daily life. At one end of the Air Garden is a flagpole and at the other a memorial and u-shaped pool containing five water jets. Drawing the eye down the length of the landscape is a series of rectangular clipped hedges of American holly, and on either side of the watercourse, a grove of honey locusts is densely planted fourteen feet on center, four trees wide.

Throughout his design Kiley took into account the needs of the campus and the Cadets daily routine. According to Jory Johnson in the essay Man as Nature: “As Kiley explains, the Air Garden is not intended to have the same sense of dominion as Versailles or other grand French gardens: ‘We have to look at where we are today. I use geometry and Le Nôtre used geometry, but we have different understandings of the universe.’ Instead of extending the prominence of a particular building or institution – the gardens of Versailles radiate from the Chateau – the Air Garden extends the life of the cadets.” Both metaphysically and physically this is the case with Kiley’s design, illustrated in the eighty-one-foot-wide promenade of white marble that surrounds the Air-Garden on four sides. The breadth of the promenade is specifically calculated in order to accommodate the strict formations of marching cadets. This rhythm is mirrored in the pathways formulated to accommodate a single cadet (four feet wide), or two (six feet wide).

.jpg) Kiley’s landscape was already in decline by the late 1950s, before the plan’s implementation was even complete. When the last building was constructed, the Air Force handed over responsibility for management and maintenance to the Army Corp of Engineers. As a result, elements of Kiley’s design were not built, including the curvilinear landscape concept around the dormitories. Over time the built landscape further declined; dead trees were not replaced, the naturalistic ravine Kiley incorporated was removed, and perceived maintenance issues led to the Air Garden’s gridded fountains being filled with sod, dramatically altering the look, feel and intent of the design. Honey locusts have proven to be poor choices in some campus areas exposed to harsh temperatures and wind. In the 1980s Air Force Academy graduates began returning to the campus in leadership roles, and pride in the school’s heritage has led to a desire for building and landscape restoration. In the 1990s the Academy commissioned restoration plans along with strategies for dealing with development encroachment from nearby communities. As a first step the fountains at the north and south ends of the Air Garden were restored to their original design. Since then, work has been slow, with funding for the project made more difficult by 2013’s sequestration. But the Air Force Academy’s leadership is committed to the plan and intends to continue with restoration efforts as funding allows.

Kiley’s landscape was already in decline by the late 1950s, before the plan’s implementation was even complete. When the last building was constructed, the Air Force handed over responsibility for management and maintenance to the Army Corp of Engineers. As a result, elements of Kiley’s design were not built, including the curvilinear landscape concept around the dormitories. Over time the built landscape further declined; dead trees were not replaced, the naturalistic ravine Kiley incorporated was removed, and perceived maintenance issues led to the Air Garden’s gridded fountains being filled with sod, dramatically altering the look, feel and intent of the design. Honey locusts have proven to be poor choices in some campus areas exposed to harsh temperatures and wind. In the 1980s Air Force Academy graduates began returning to the campus in leadership roles, and pride in the school’s heritage has led to a desire for building and landscape restoration. In the 1990s the Academy commissioned restoration plans along with strategies for dealing with development encroachment from nearby communities. As a first step the fountains at the north and south ends of the Air Garden were restored to their original design. Since then, work has been slow, with funding for the project made more difficult by 2013’s sequestration. But the Air Force Academy’s leadership is committed to the plan and intends to continue with restoration efforts as funding allows.

1 Kiley, Dan and Jane Amidon, Dan Kiley: The Complete Works of America’s Master Landscape Architect (Boston, New York, London: Little, Brown and Company, 1999), 28.

2 Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, United States Air Force Academy Base Comprehensive Plan: Cadet Area Master Plan (1985), 62.

3 Kiley, Dan and Jane Amidon, Dan Kiley: The Complete Works of America’s Master Landscape Architect (Boston, New York, London: Little, Brown and Company, 1999), 29.

4 Johnson, Jory. “Man as Nature” In Modernism at Mid-Century: The Architecture of the United States Air Force Academy, ed. Robert Bruegmann (University of Chicago Press, 1995), 116.

Nauman, Robert Allen, “Preserving a Monument: The United States Air Force Academy,” Future Anterior 1, no. 2 (Fall 2004):33-41, http://www.arch.columbia.edu/files/gsapp/imceshared/aml2193/Nauman_4.pdf.

Hill, David. “Air Age Gothic,” Preservation (May/June 2008), http://www.preservationnation.org/magazine/2008/may-june/air-age-gothic.html.

Hosington, Daniel J. “National Historic Landmark Nomination: United States Air Force Academy, Cadet Area,” http://www.nps.gov/nhl/designations/samples/co/usafa.pdf, (accessed October 31, 2013).

Johnson, Jory. “Man as Nature”In Modernism at Mid-Century: The Architecture of the United States Air Force Academy, ed. Robert Bruegmann (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994), 102-120.

Kiley, Dan and Jane Amidon. Dan Kiley: The Complete Works of America’s Master Landscape Architect (Boston, New York, London: Little, Brown and Company, 1999), 28-31.

“Landscape Design: Works of Dan Kiley.” Process: Architecture 33. (Tokyo: Japan, Process Architecture Publishing Co., 1982), 48-51.

Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, United States Air Force Academy Base Comprehensive Plan: Cadet Area Master Plan (1985).

The Cultural Landscape Foundation. “What’s Out There: United States Air Force Academy,” http://tclf.org/landscapes/united-states-air-force-academy.

.jpg)

.jpg)