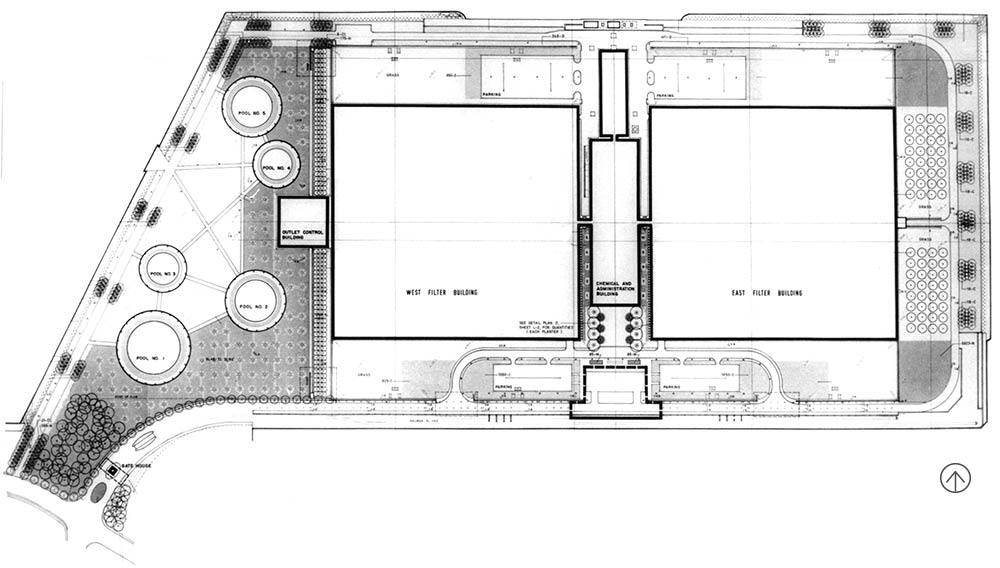

The Central District Filtration Plant (now known as the Jardine Water Purification Plant) is the largest water management facility in the U.S. The plant was constructed on a man-made landmass that juts out into Lake Michigan from the Chicago shoreline. The site is separated into two portions, to the east the massive filtration plant (an underground reservoir, labs, pump-rooms and administration offices), which occupies the majority of the sixty-one-acre site and to the west, Milton Lee Olive Park, a ten-acre public park that serves as a gateway to the plant. Kiley collaborated with architect Stan Gladych of the firm C.F. Murphy to produce the plans for the site.

.jpg)

Kiley’s design for the filtration plant landscape is functional, yet retains his signature aesthetic. The plant entry is separate from that for the public park. A drive lined on one side by trees leads to the utilitarian landscape, separated from the park for security purposes (mass plantings of hawthorns provide a dense physical barrier between the plant and park). Once inside the gate, a narrow band of landscaping surrounds the massive structure. The simple design includes an entry court and outdoor picnic area, set under bosques of trees along the water on the property’s eastern edge. The site is it susceptible to a variety of environmental conditions, including high winds and extreme temperature fluctuation. Consequently, the plant materials are predominated by very hearty and tolerant including honey locusts (a Kiley favorite), hawthorn and barberry. These same plant materials are used in the park, where groves of honey locusts arch over a paved pedestrian path that runs along the western edge of the promontory.

The main body of the park landscape consists of five stepped, aerating, circular fountains of varying circumference, connected by diagonal walks. According to John Beardsley, “The site’s character is beautifully and simply expressed in five pools of different sizes scattered irregularly in the park like an extinguished constellation – or like stones in a Japanese garden, as Kiley insisted … In Kiley’s mind, they also symbolized the five Great Lakes; we might also recognize in them an asymmetrical echo of Le Nôtre’s water parterres.” Kiley himself says, “My first thought when I visited the site was of moon craters – huge, shallow pockmarks in the ground that would seem to fill up with water from below, as if the reservoir was seeping up to the surface.” Swaths of manicured lawn gently undulate between the fountains, setting the pools at subtly different levels. The fountains at Milton Lee Olive Park are capable of spouting water one hundred-feet high – a phenomenon that, when the fountains are in full-use, can be viewed from the nearby high-rise buildings along Lake Shore Drive. The park also features a statue, Hymn to Water, by Milton Horn, and a monument to Milton Lee Olive, III (1946-1965), the first African American recipient of the Medal of Honor in the Vietnam War.

.jpg)

According to Kiley, “The 1965 public relations brochure of the Department of Public Works proclaimed that the plant ‘symbolizes the city’s motto’ Urbs in Horto – City in a Garden – the ideal that a great metropolis can live and grow in harmony with nature’.” While still extant, the landscape at Milton Lee Olive Park is showing the signs of deferred maintenance. Paving is cracked and the fountain pools are often dry. When in use the fountain spray rarely exceeds a height of eight-feet, an energy saving feature that unfortunately alters Kiley’s original concept for the design. Repairs to the paving and other hardscape features, and work to restore the fountains to full-function would re-enliven the park for both residents and visitors alike.

1 Beardsley, John. “Dan Kiley in Public.” In Dan Kiley Landscapes: The Poetry of Space, ed. Reuben M. Rainey and Marc Treib (Richmond, CA: William Stout Publishers, 2009), 109.

2 Kiley, Dan and Jane Amidon, Dan Kiley: The Complete Works of America’s Master Landscape Architect (Boston, New York, London: Little, Brown and Company, 1999), 37.

3 Ibid., 39.

Charles Waldheim, FAAR, 2013

Based on his experience working with Kiley on the Air Force Academy project, Chicago architect Stan Gladych recommended Kiley to C.F. Murphy for the Jardine Water Filtration Plant project after a previous scheme by Hideo Sasaki had been rejected as unfeasible. Based on the success of the Kiley landscape and public reception of the Water Filtration Plant, Murphy was subsequently awarded the largest public works commission in the city’s history, the design of O’Hare Airport. Regrettably, Murphy didn’t include Kiley, or any landscape architect, in the O’Hare team. As a result, the most important airport in the jet-age world failed miserably to produce a public landscape equal to its architectural innovation.

Kiley’s subsequent collaboration with C.F. Murphy Associates on the Jardine Water Filtration Plant on Chicago’s lakefront, features another aerial garden. In this instance, the garden was to provide an aerial view for the ‘cliff-dwelling’ residents of the gold coast’s hi-rise apartment buildings. The project included the landscape for the Jardine Plant itself, as well as an adjacent public park. Kiley’s Milton Lee Olive Park was named for the first African-American recipient of the Congressional Medal of Honor in the Vietnam era, Milton Lee Olive III. The park features a classical Kiley allée of locust trees extending toward the horizon and culminating in a cantilevered plane. The main structuring device of the park is a set of five large fountains recalling the Great Lakes. These vast pools invoke the rhetorical dimension of the largely prosaic function of the water treatment facility to the east. Kiley’s design unites the public works facility with the public park through the representation of water and the regular repetition of similar species across the profane act of cleansing and the sacred act of remembrance.

.jpg)

.jpg)