-

“You will walk on water!” This Kiley wrote is what he told a “startled” Harry Cobb (of Pei, Cobb, Freed architects), when they first visited the site for Fountain Place in Dallas. However, according to Kiley colleague Ian Tyndall, it wasn’t the first time Kiley had proposed a water garden. In a conversation with Charles A. Birnbaum, TCLF’s founder and president, Tyndall related how Kiley had proposed a similar design twenty-three years earlier for the Art Institute of Chicago, South Garden, but was rebuffed.

Here there would be no such rebuttal, the design for the plaza, completed just two years after the Dallas Museum of Art project, turned a six-acre site on the edge of the city’s now flourishing Arts District into a cascading fountain of water set beneath a shady canopy of indigenous bald cypress trees. Process Architecture called it: “[T]he most extensive water garden constructed since the Renaissance” – depending on how “extensive” is interpreted, it could be argued that the Lawrence Halprin-designed Open Space Sequence in Portland, OR, created between 1965 and 1978, claims that mantle.

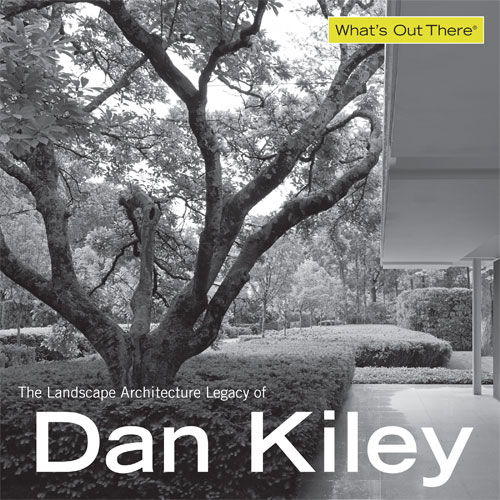

Regardless, landscape architect Gary Hilderbrand describes it as a “forested lagoon” that “glimmers with reflected light.” Meanwhile, architect Yoji Sasaki wrote: “At Fountain Place … the master space becomes a floor of water.”

.jpg) Kiley envisioned the plaza, which sits at the foot of the Fountain Place Office Development, as an urban swamp, which would transport visitors out of their surroundings, creating a cool respite from the city’s noise and heat. The structure of the plaza, a collaboration with Peter Ker Walker and WET Design, is laid out on a strict grid broken only by the footprint of a 60-story glass office tower by Harry Cobb. The design takes advantage of a natural 12-foot grade-change between Ross Avenue and Field Street, which border the plaza to the east and west. Wide pools of water, which occupy 70% of the site, surround the building and a central plaza located to the north. Where steps accommodate the grade change the pools of water are terraced, creating a series of flowing waterfalls that, along with low bubbler jets, activate the space. Round concrete planters that hold 200 bald cypress (see below) trees are positioned at fifteen-foot intervals within the grid. The trees serve a strategic role in the site’s design, creating a false sense of space, upwards to the top of their canopies and outwards. The reflective glass façade of the office tower amplifies the effect giving the impression of a forest beyond.

Kiley envisioned the plaza, which sits at the foot of the Fountain Place Office Development, as an urban swamp, which would transport visitors out of their surroundings, creating a cool respite from the city’s noise and heat. The structure of the plaza, a collaboration with Peter Ker Walker and WET Design, is laid out on a strict grid broken only by the footprint of a 60-story glass office tower by Harry Cobb. The design takes advantage of a natural 12-foot grade-change between Ross Avenue and Field Street, which border the plaza to the east and west. Wide pools of water, which occupy 70% of the site, surround the building and a central plaza located to the north. Where steps accommodate the grade change the pools of water are terraced, creating a series of flowing waterfalls that, along with low bubbler jets, activate the space. Round concrete planters that hold 200 bald cypress (see below) trees are positioned at fifteen-foot intervals within the grid. The trees serve a strategic role in the site’s design, creating a false sense of space, upwards to the top of their canopies and outwards. The reflective glass façade of the office tower amplifies the effect giving the impression of a forest beyond.

.jpg) Slate walkways, stairs and ramps that sit flush with the water provide circulation through the site. An open plaza to the north becomes a central gathering area, edged by benches and moveable seating. At its center, a square grid of water jets is set into the slate paving. The jets, which are electronically engineered to spray water in alternating patterns, provide notes of drama. This water show can be turned on or off as necessary to open up the plaza for large events. To the rear of the plaza, sits a plane of water and grove of cypress trees, this one flat, activated only by the gurgling of the low bubblers. Each of the 220 bubblers in the garden is lit at night, creating a glowing refuge.

Slate walkways, stairs and ramps that sit flush with the water provide circulation through the site. An open plaza to the north becomes a central gathering area, edged by benches and moveable seating. At its center, a square grid of water jets is set into the slate paving. The jets, which are electronically engineered to spray water in alternating patterns, provide notes of drama. This water show can be turned on or off as necessary to open up the plaza for large events. To the rear of the plaza, sits a plane of water and grove of cypress trees, this one flat, activated only by the gurgling of the low bubblers. Each of the 220 bubblers in the garden is lit at night, creating a glowing refuge.

As Sasaki observed: “Only the sound of water can be heard. Among the trees, our urban sense of time is gently altered. Even in Dallas, a city covered with asphalt, we discover a place where we can be at home with ourselves.”

1 Kiley, Dan and Jane Amidon, Dan Kiley: The Complete Works of America’s Master Landscape Architect (Boston, New York, London: Little, Brown and Company, 1999), 98.

2 Process: Architecture 108: Dan Kiley: Landscape Design II. (Tokyo: Japan, Process Architecture Publishing Co., 1993), 36.

3 Sasaki, Yoji, “Natural Man, Dan Kiley”, Process: Architecture 108: Dan Kiley: Landscape Design II. (Tokyo: Japan, Process Architecture Publishing Co., 1993), 24.

4 Sasaki, Yoji, “Natural Man, Dan Kiley”, Process: Architecture 108: Dan Kiley: Landscape Design II. (Tokyo: Japan, Process Architecture Publishing Co., 1993), 24.

-

Gary Hilderbrand, FASLA, 2013

You can easily pick out Fountain Place on the Dallas skyline as you approach the city from the north: Harry Cobb’s precisely chiseled, shape-shifting mass rises elegantly amid dozens of less confident neighbors. When you arrive at the corner of Ross Avenue and North Field Street, on the edge of the Arts District, Fountain Place’s big volume cuts back and lands, almost impossibly, on the edge of a forested lagoon. It’s a thoroughly watery place that glimmers with reflected light and rushing currents in the shade of more than 200 bald cypress trees. It seems as if you’ve descended into a bottomland swamp that’s been organized for easy passage and drenched with an atmosphere that makes you want to linger. You’re surrounded with dampness. When the air on the street is hot and dry, as it can be for months in Dallas, this place is cooling and refreshing. And transporting. There isn’t another plaza like it. It’s one of a kind.

I don’t usually go in for drama in urban public space. I like calm. But Fountain Place is crazy theater, and it brings me joy, every time. I don’t want to overstate it, but for me it has a “must-go” draw, each time I come to Dallas. Like making a routine pilgrimage to the Pantheon in Rome or stopping at Barney’s in New York, no trip to Dallas is complete without soaking up a few minutes in one of nature’s coolest dead-ringers.

It’s not widely known that this project came along during the breakdown of a long professional relationship between Peter Ker Walker and Dan Kiley. Walker carried Fountain Place forward through implementation (along with the newly-formed Wet Design consulting firm) and he rarely sees any credit for it. But it’s no surprise that we identify Fountain Place with Kiley. It’s riddled with his maniacal order, with the smell and feel of reorganized nature. Big sums of bravado and conviction made Fountain Place happen. That’s Kiley for you.

-

Texas Society of Architects. “Fountain Place Wins 25-Year Award,” https://texasarchitects.org/v/article-detail/Fountain-Place-Wins-25-Year-Award/3q/.

Landscape Voice. “Fountain Place,” http://landscapevoice.com/fountain-place/.

Pei Cobb Freed & Partners. “Fountain Place (originally Allied Bank Tower) – Phase 1,” http://www.pcf-p.com/a/p/8212/s.html.

Hazelrigg, George, “Still Walking On Water,” Landscape Architecture, October 2006, http://www.asla.org/lamag/lam06/october/editorschoice.html.

Public Art Walk Dallas, “Fountain Place,” http://www.publicartwalkdallas.org/en/art/6.shtml.

Rome, Richard, “The Dallas Waterworks,” Cite 29 (Fall 1992-Winter 1993):31-32, http://citemag.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/DallasWaterworks_Rome_Cite29.pdf.

Fountain Place, “The Building,” http://www.fountainplace.com/building/.

The Cultural Landscape Foundation. “What’s Out There: Fountain Place,” http://tclf.org/landscapes/fountain-place.

Kiley, Dan and Jane Amidon. Dan Kiley: The Complete Works of America’s Master Landscape Architect (Boston, New York, London: Little, Brown and Company, 1999), 98-105.

“Dan Kiley: Landscape Design II.” Process: Architecture 108. (Tokyo: Japan, Process Architecture Publishing Co., 1993), 36-45.

.jpg)

.jpg)