Biography

Daniel Urban Kiley was born in Boston, MA, in 1912. He grew up and attended public schools, graduating high school in 1930.

In 1932 he began a four-year apprenticeship with Warren Manning, a significant figure in the profession who worked for Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr. from 1888-1896 and was a founder of the American Society of Landscape Architects. At Manning’s Harvard Square office in Cambridge, MA, Kiley learned the rudiments of office practice and procedure, drafting, and some design. As Kiley recalled in a 1982 lecture: “As a kid I would drive Manning all over the place in a Model A convertible. I really learned many things from him about plant materials, because he was a great expert.” Because he was outgoing and quick-witted, Kiley was often assigned to construction supervision, plant materials selection from nurseries, as well as transplanting materials from various site locations – this work became an important foundational experience of his own long practice. His interest in extending the planting possibilities in use and location is at the heart of his design innovation.

In 1936 Kiley entered the landscape architecture program at Harvard University. Harvard at that time was undergoing a revolutionary curriculum change in the architecture department with the arrival of Walter Gropius and his colleagues from the Bauhaus in Germany. The landscape department, however, was less driven by an interest in Modernism than by the study of estate gardens, the Beaux Arts traditions and faculty advocacies of naturalism versus formalism. Kiley and his classmates Garrett Eckbo and James Rose, while accepting the earlier ideas of the Olmsteds, were extremely interested in the emerging European social, spatial, and artistic interests. The three classmates were involved in a series of confrontations, both in design and theory, in which they attempted to adapt, without the aid of Gropius, the new architectural thinking to landscape design. Their joint efforts can be read in three articles published in Pencil Points in 1939 and 1940. Kiley left Harvard in 1938 without graduating. He worked briefly for the National Park Service in Concord, NH, and then in Washington, D.C., at the United States Public Housing Authority under Elbert Peets. There he met the young architect Louis Kahn.

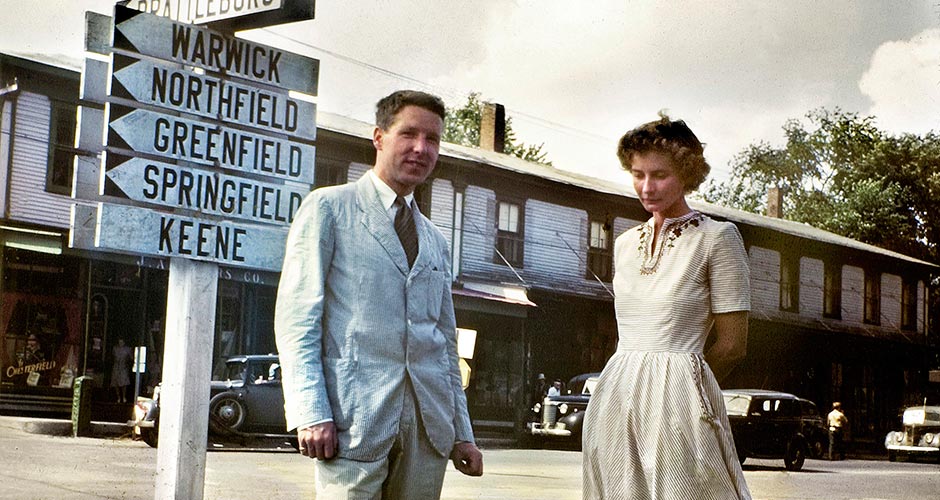

In 1942 he married Anne Lathrop Sturges and opened his own office in Franconia, NH. He was licensed to practice architecture in New Hampshire in 1943 with a recommendation from Kahn and Eero Saarinen, who he had also met in Washington, DC.

From 1943 to 1945, Kiley served in the U.S. Army. Due to his design background, he worked with the presentations branch of the Corps of Engineers in the Office of Strategic Services, where he became director of the design staff. At the end of the war in Europe, Kiley was assigned the task of laying out the courtroom for the war crimes trials at Nuremberg. While in Europe, he first visited the German countryside and the great French gardens of André Le Nôtre and others. The European landscape and these gigantic formal works left a strong impression on Kiley - he recalled: “[T]he opportunity to travel around Western Europe and, for the first time in my life, to experience formal, spatial built landscapes (as championed in France by André Le Nôtre at its grandest, most rarefied level, yet found on every street of tiny towns and cities). THIS was what I had been searching for – a language ... to reveal nature’s power and create spaces of structural integrity. I suddenly saw that lines, allées and orchards/bosques of trees, tapis verts and clipped hedges, canals, pools and fountains could be tools to build landscapes of clarity and infinity, just like a walk in the woods.”

And yet one can clearly see in Kiley's work both the monumental clarity of the French Baroque gardens and the influence of the classical constructivist and spatial elements in the early Post War works of his colleagues, the new generation of American architects. As the American built environment exploded in the 1950s, Kiley was one of the few practitioners of Modern landscape architecture, particularly on the East Coast and in the Midwest. After a beginning in residential and housing design and a brief trip to the West Coast to visit his friend Eckbo and see the work of Thomas Church and the developing group of California Modernists, he chose to continue his practice first in New Hampshire and later in Vermont. He chose these locations in part because of his love of skiing and hiking. He and his wife Anne supplemented his design income as ski instructors during his early years of practice.

Kiley’s professional contacts, particularly with the first generation of American Modern architects such as Eero Saarinen, I.M. Pei, Louis Kahn, and Gordon Bunshaft, provided not only professional opportunities but shaped his design approach and direction as well. Some of his important early projects came into his office through these associations. Between 1946 and 1968, operating his firm as the Office of Dan Kiley, Kiley produced some of his most iconic projects. In 1946 he was on the winning team with Eero Saarinen for the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial competition, known as the St. Louis Arch, and in 1955, again with Saarinen, he designed the garden for J. Irwin Miller's family in Columbus, IN, perhaps the most important Post War garden in the U.S. In 1963 he designed the gigantic approach gardens for Saarinen's Dulles Airport outside Washington, DC. In 1968 Kiley and Walter Netsch of Skidmore Owings and Merrill (SOM) designed the gardens for the new U.S. Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, CO. Kiley also worked with Saarinen’s successor firm, Kevin Roche John Dinkeloo Associates, on the Ford Foundation atrium in New York in 1964 and the rooftop gardens at the Oakland Museum of Art in 1969.

Between 1971 and 1986 Kiley partnered with colleagues, operating as Kiley Tyndall Walker for eight years with Ian Tyndall and Peter Ker Walker (both Scotsmen who joined Kiley’s practice early on), and as Kiley Walker until 1986 when the firm name returned to the Office of Dan Kiley. In this time of active partnership the firm completed significant projects, including the Dallas Museum of Art and Fountain Place both in Dallas, in the early 1980s; the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC; and work abroad, including l’Esplanade du Général de Gaulle at La Défense in Paris, France.

Some of Kiley’s most notable residential work was completed in the last ten years of his career, including Kenjockety in Westport, NY, the Kimmel Residence in Salisbury, CT, and Patterns in Wilmington, DE, designed for Governor Pierre S. “Pete du Pont IV and his wife Elise.

Some of Kiley’s most notable residential work was completed in the last ten years of his career, including Kenjockety in Westport, NY, the Kimmel Residence in Salisbury, CT, and Patterns in Wilmington, DE, designed for Governor Pierre S. “Pete du Pont IV and his wife Elise.

Unlike many of his contemporaries Kiley rarely wrote or taught. Yet in his office he apprenticed, and worked with such distinguished designers and teachers as Richard Haag, Joe Karr, Peter Hornbeck, Peter Ker Walker, Ian Tyndall, Henry Arnold, Cornelia Oberlander, Peter Schaudt, Gregg Bleam, Peter Morrow Meyer and many, many others. He was awarded the National Medal of Arts in 1997, the highest award given to artists and arts patrons by the U.S. government, and the Lifetime Achievement award from the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum in 2002.

Like other Post War landscape architects, Kiley has many important works that were not properly built or maintained. Nevertheless, many of Kiley's projects remain intact today, cared for by thoughtful private and institutional stewards who understand and value Kiley’s design and legacy.

Based on the essay by Peter Walker for Shaping the American Landscape.

1 Kiley, Dan. “Lecture” in Dan Kiley Landscapes: The Poetry of Space, ed. Reuben M. Rainey and Marc Treib (Richmond, CA: William Stout Publishers, 2009), 22.

2 Kiley, Dan and Jane Amidon, Dan Kiley: The Complete Works of America’s Master Landscape Architect (Boston, New York, London: Little, Brown and Company, 1999), 12-13.

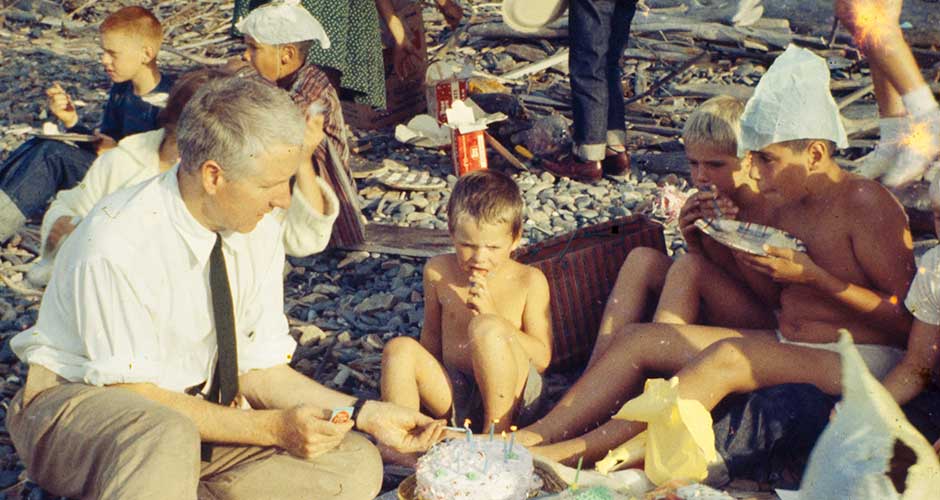

Photos courtesy of Aaron Kiley.