In 1958 Stephen and Audrey Currier established a nearly 5000-acre rural estate in the foothills of the

Green Mountains, called Smokey House Farm. The property was largely undeveloped forest except for an abandoned marble quarry, a small farmhouse and the remnants of the property’s historic stone walls. In 1959 the Curriers engaged Dan Kiley to create a Modernist landscape, wedding the old farmstead with the surrounding streams and woodlands. The project shows the development and maturation of geometry in Kiley’s design.

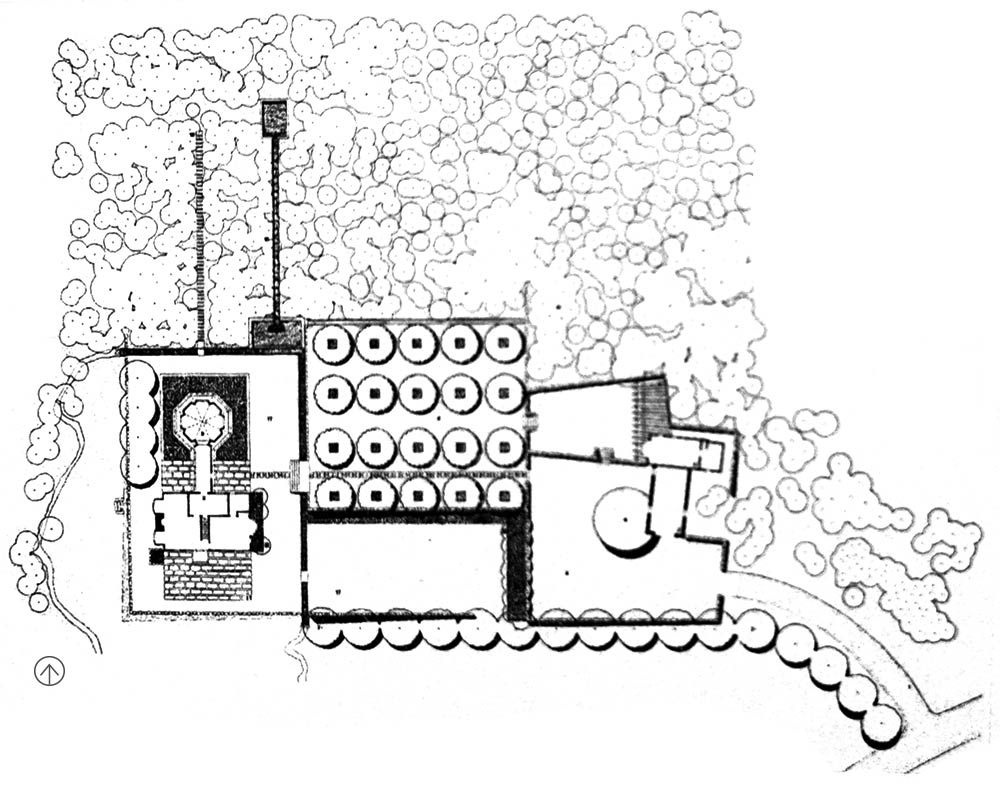

The residence comprises a series of three distinct geometrical spaces terraced into the hillside. A drive winds uphill through a hardwood forest before reaching the house, which is perched on a summit with views over rolling fields. Kiley lined the drive with sugar maples and enclosed the parking court with low fieldstone walls (incorporated into the design from the original property) and a lilac hedge. North of the court he positioned a garage and guesthouse elevated a few feet above grade, with the nearby lawn and trellis accessed via broad, marble steps that bridge a fieldstone wall. An adjacent apple orchard with twenty trees planted eight feet on center separates the main and guest houses. While the elements of the design are formal, they also feel rustic. Kiley said described his thinking this way: “In terms of formal effect, the orchard and other elements of the Currier design certainly can be traced to classical roots. But here, as with the majority of my schemes, the classic structure and local materials have been employed to reveal a modern spatial sensibility. The two operate simultaneously.”

Marble steps descend from the orchard two feet to the house, crossing a narrow, stream-fed rill. Marble paving wraps around the house, while an octagon-shaped building addition extends from the farmhouse and into a sunken garden filled with herbs, ferns, and shrubs. With the unfortunately passing of the Curriers in 1967, the estate passed to the Taconic Foundation and in 1974 opened as the Smokey House Center. Today the residence and thirteen acres are privately owned, while the Center has put 4,417 acres of woods and farmland under conservation easement.

Marble steps descend from the orchard two feet to the house, crossing a narrow, stream-fed rill. Marble paving wraps around the house, while an octagon-shaped building addition extends from the farmhouse and into a sunken garden filled with herbs, ferns, and shrubs. With the unfortunately passing of the Curriers in 1967, the estate passed to the Taconic Foundation and in 1974 opened as the Smokey House Center. Today the residence and thirteen acres are privately owned, while the Center has put 4,417 acres of woods and farmland under conservation easement.

A passage from Reuben Rainey and Marc Treib’s book Dan Kiley Landscapes: The Poetry of Space captures the essence of what Kiley accomplished at Currier: “Kiley embraced a humanistic point of view. For him it was not “man and nature” or “man with nature,” but “man is nature.” He understood ecology and its influence on design, but never attempted to replicate the literal appearance of nature in his landscapes. Instead, he sought the principles of order and the processes behind natural systems and transformed them – often through the “classical” landscape elements of the bosque, the parterre, the terrace, the allée, and the axis – to create engaging, at times delightful, settings for human activity.”

1 Kiley, Dan and Jane Amidon, Dan Kiley: The Complete Works of America’s Master Landscape Architect (Boston, New York, London: Little, Brown and Company, 1999), 44.

2 Rainey, Reuben M. and Marc Treib. “Dan Kiley: An Introduction”In Dan Kiley Landscapes: The Poetry of Space, ed. Rueben M. Rainey and Marc Treib (Richmond, CA: William Stout Publishers, 2009), 10.

Gregg Bleam, 2013

The day was overcast and I was lost in the Green Mountains of Vermont trying to follow Dan Kiley’s cryptic scrawl of a map leading me from his office in East Charlotte, Vermont to the Currier Farm outside Danby. Earlier in the day, I had been interviewing Dan about the Miller Garden and decided to visit Kiley’s much smaller Currier project afterward. After asking directions from a farmer or two, I finally made a sharp turn up the hill marked by a simple line of sugar maples on one side and a grove of paper birch on the other. Arriving in front of a stacked stone wall backed by the contorted branches of a lilac hedgerow, I was immediately struck by the quiet elegance of the garden beyond. Ironically, I had come to Vermont with the intention of discussing what is arguably Dan’s most important work, the Miller Garden, but would leave being more impressed by the contextual minimalism of Currier Farm.

The day was overcast and I was lost in the Green Mountains of Vermont trying to follow Dan Kiley’s cryptic scrawl of a map leading me from his office in East Charlotte, Vermont to the Currier Farm outside Danby. Earlier in the day, I had been interviewing Dan about the Miller Garden and decided to visit Kiley’s much smaller Currier project afterward. After asking directions from a farmer or two, I finally made a sharp turn up the hill marked by a simple line of sugar maples on one side and a grove of paper birch on the other. Arriving in front of a stacked stone wall backed by the contorted branches of a lilac hedgerow, I was immediately struck by the quiet elegance of the garden beyond. Ironically, I had come to Vermont with the intention of discussing what is arguably Dan’s most important work, the Miller Garden, but would leave being more impressed by the contextual minimalism of Currier Farm.

My visit to this small project in the summer of 1992 has influenced my own work as a landscape architect in many ways, but I will focus on three. First, Kiley believed in the importance of the diagram. When I worked for Dan in the early 1980s he always insisted that we get each project’s diagram right before developing the design. At Currier the landscape is essentially a built diagram: three garden spaces, three grade changes, site walls aligned with the house and view to the mountains. Secondly, the connection to site or place is significant. In many ways landscape architecture is always a renovation. The landscape architect is always starting from a certain number of constraints. At Currier, Kiley re-interprets the traditional Vermont Farm planting typology—a row of sugar maples, the gridded planting of the apple orchard, the lilac hedge row, lawn panel and perennial garden—as Modernist form. Native stacked fieldstone and white marble from the nearby quarry also connect the design to the site. Finally, Kiley’s use of water as an integral structure in the landscape has influenced my work. Each of the three gardens uses water as a threshold. To enter the house one must cross the “floating” steps over the runnel. Likewise one must step on a stone plank to cross the runnel to enter the lawn and perennial garden from the house. By Kiley’s thoughtful placement of the water tank and runnel, the three parts of this simple garden scheme are simultaneously stitched together and yet made distinct. In this way the mountainside landscape and spring seamlessly connect to the orthogonal geometry of the garden. The importance of the diagram, the connection of materials to the site, and the use of water as threshold are principles that have deeply influenced me and continue to be foundational to the work that I do.

Reid, Melinda.” New Purpose for a Modern Garden: Rehabilitating Dan Kiley’s Currier Farm.” Unpublished manuscript, terminal project, University of Massachusetts at Amherst, 1999.

Kiley, Dan and Jane Amidon. Dan Kiley: The Complete Works of America’s Master Landscape Architect (Boston, New York, London: Little, Brown and Company, 1999), 44-47.

“Landscape Design: Works of Dan Kiley.” Process: Architecture 33. (Tokyo: Japan, Process Architecture Publishing Co., 1982), 43.

The Cultural Landscape Foundation. “What’s Out There: Currier Farm,” http://tclf.org/landscapes/currier-farm.