“Give us Shangri-La.” This, recalls Kiley colleague Ian Tyndall, was the mandate Clarence and Muriel Hamilton gave Dan Kiley, Peter Ker Walker, and Tyndall in the late 1950s when their firm was commissioned to design the landscape for the Hamilton's modest Modernist ranch-style home. The Hamiltons lived in Columbus, IN, where Kiley had recently created his influential masterwork, the Miller Garden. As Kiley recalled, “[W]e had the opportunity to do … [a] house for a man named Clarence Hamilton. When I first went to him, I said, ‘Clarence, you should sell your house (it was just an ordinary suburban house looking onto the road), and I’ll get you the best architect in the world and a new site.’ He said, ‘Well, Muriel likes it here so well, and we really want to go to town on the landscape.”

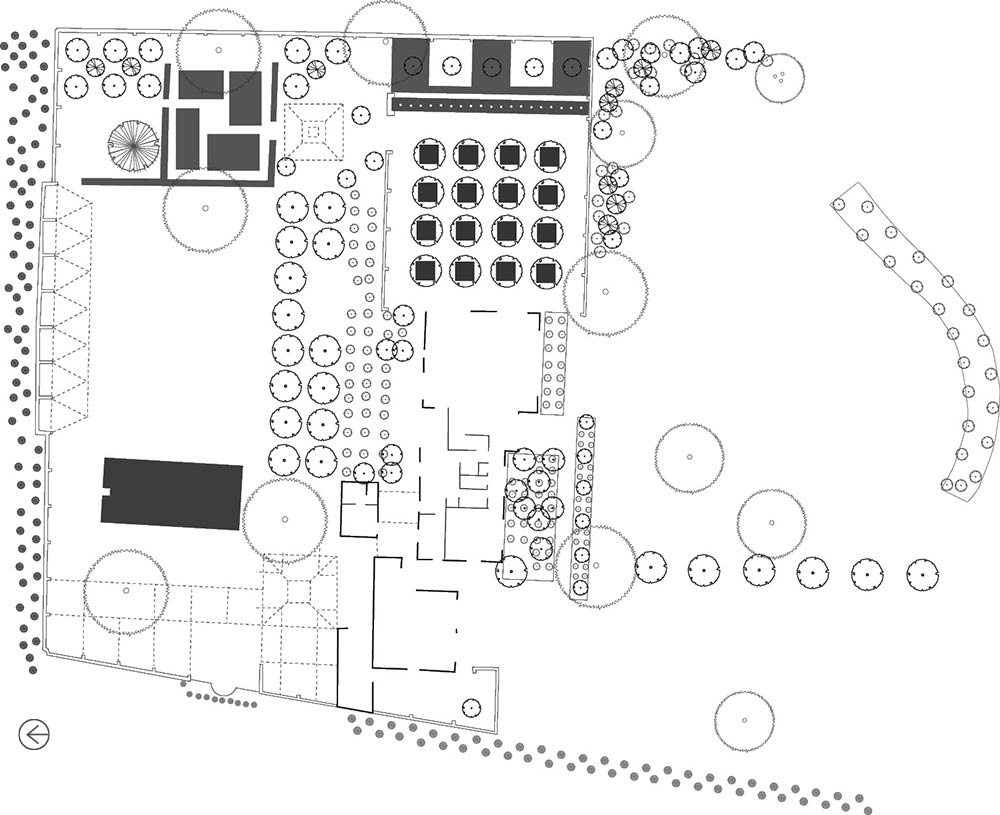

The Hamilton’s envisioned their garden as a private oasis, and they were prepared to go to great expense to achieve their vision. The property is set on a small half-acre lot. The house faces onto an informal front lawn defined by curvilinear plantings of crepe myrtle, yew, and quince that screen it from the street. A row of six sugar maples lines the entry drive and foundation plantings soften the structural edge of the house. As Tyndall opined, it “presents an inscrutable public face.” The rear garden was to become the Hamilton’s paradise, and it would be different from the modest planting at the Hamilton Cosco offices, which Tyndall called, “an economical exercise in geometry.”

The major design factor that shaped the project was Kiley’s daring decision to construct a seven-foot-high, yellow-brick privacy fence around the garden – a fence longer than a football field in length. “It took [Mr. Hamilton] a minute to realize that Dan’s extravagant proposal had just brought his dream within reach,” said Tyndall.

Kiley used a geometric layout to establish structure in the rear garden, utilizing allées, bosques and a long wooden pergola set on brick columns to create a sequence of spaces organized around a rectilinear swath of open lawn. Sheltered views open up from each of the garden’s elements, and the use of both horizontal and vertical features expand the visitor’s sense of space.

.jpg) To the side of the house a bosque of littleleaf lindens is arranged in a gravel court enclosed by a low brick wall lined with benches. Each tree is set in a square bed planted with pachysandra and annuals. A linear water channel activated by a row of projecting fountain jets provides a structural element along one side of the grove, and seasonal color is added by a row of five crepe myrtles positioned behind the fountain.

To the side of the house a bosque of littleleaf lindens is arranged in a gravel court enclosed by a low brick wall lined with benches. Each tree is set in a square bed planted with pachysandra and annuals. A linear water channel activated by a row of projecting fountain jets provides a structural element along one side of the grove, and seasonal color is added by a row of five crepe myrtles positioned behind the fountain.

Adjacent to the bosque, an open-air pavilion serves as the eastern terminus of an allée of honey locusts, which runs parallel to the rear elevation of the house. At the allée’s western end is a similar glass-enclosed dining pavilion that looks out onto a rectangular swimming pool and brick patio with an outdoor fireplace.

Completing the design is a wooden wisteria-laden arbor set on brick piers that spans the back edge of the property. Connecting to flower gardens and enclosed by a hornbeam hedge, the arbor mirrors the locust allée on the opposite side of the lawn.

Completing the design is a wooden wisteria-laden arbor set on brick piers that spans the back edge of the property. Connecting to flower gardens and enclosed by a hornbeam hedge, the arbor mirrors the locust allée on the opposite side of the lawn.

As Tyndall noted: “All quintessential Kiley.”

Between 1981 and 1986 the property changes hands several times and is now owned by a private corporation who have been faithful stewards of it. The Hamilton Garden has been carefully renewed and maintained as the Shangri-La its original owners had intended. Based on recent preservation and rehabilitation efforts undertaken by the present owners, and their willingness to open the garden for occasional private tours, there is tremendous respect, enthusiasm and sensitivity for this early, extant residential commission.

1 Kiley, Dan. “Lecture”In Dan Kiley Landscapes: The Poetry of Space, ed. Reuben M. Rainey and Marc Treib (Richmond, CA: William Stout Publishers, 2009), 27.

Ian Tyndall, 2013

“Give us Shangri-La.” Perhaps the Hamiltons thought this was a reasonable request, for they loved their neighborhood and the comfortable ranch house on Tipton Lane.

Dan had previously designed a modest planting at the Hamilton Cosco offices. It was exactly what was called for — an economical exercise in geometry. Was this a guide to the budget for Shangri-La? We were curious, but clueless. At our first meeting, Dan resolved that question when, out of the blue, he asked me what it would cost to build an 8-foot-high brick wall around the garden — a wall longer than a football field. Later, as I got to know him better, Mr. Hamilton confessed that when he heard my response, his first thought was that this should be our last visit and it took him a minute to realize that Dan’s extravagant proposal had just brought his dream within reach.

What was Shangri-La to be? The front yard presents an inscrutable public face, but within the garden wall Dan’s favorite landscape devices are fully deployed, dividing and overlapping one another with purpose. His familiar grid of trees becomes shaded garden room. The ubiquitous allée of Honey Locust trees focuses on the small gazebo that originally held a fountain by Charlie Perry, while on the other axis it creates a scrim between the house and the majority of the garden, lending the lawn and swimming pool the air of a place apart. All quintessential Kiley.

Hidden from the outside world, Mr. and Mrs. Hamilton cherished their garden Shangri-La. Dan had given us all a lesson on taking care of the underlying problem at the start

.jpg)