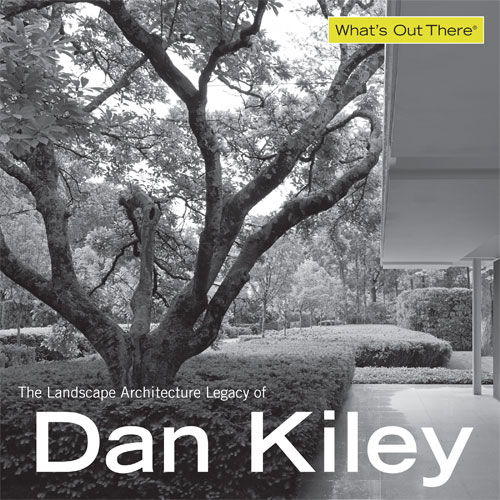

Considered to be his residential masterpiece and an iconic Modernist garden, this thirteen-acre property was developed as a unified design through the close teamwork of Dan Kiley, architects Eero Saarinen and Kevin Roche, and interior designer Alexander Girard. It was designed and constructed between 1953 and 1957 for the family of J. Irwin and Xenia Miller of Columbus, IN, who were active in the design collaboration.

Kiley met Saarinen through Louis Kahn, while he was employed at the U.S. Housing Authority in Washington, DC. They first collaborated in 1944 on an unrealized design for a competition to create a new Parliament Building in Ecuador’s capitol city of Quito. Three years later, in 1947, the pair teamed up again, this time producing the winning design for the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial in St. Louis, MO.

.jpg)

When Saarinen enlisted Kiley in 1955 to develop the landscape, plans for the house were already complete. The site, however, was a blank slate, which gave Kiley free rein. The result was a design that balanced Modern and classical elements and marked the onset of his mature design vocabulary. Jory Johnson, in Modern Landscape Architecture: Redefining the Garden, wrote: “[T]he Miller House is one of America’s first truly contemporary residential landscape designs to reject the revival solutions or the eclecticism that had dominated American estates in the first half of the twentieth century.” Peter Walker said: ''For many of us, that was where modernism began.”

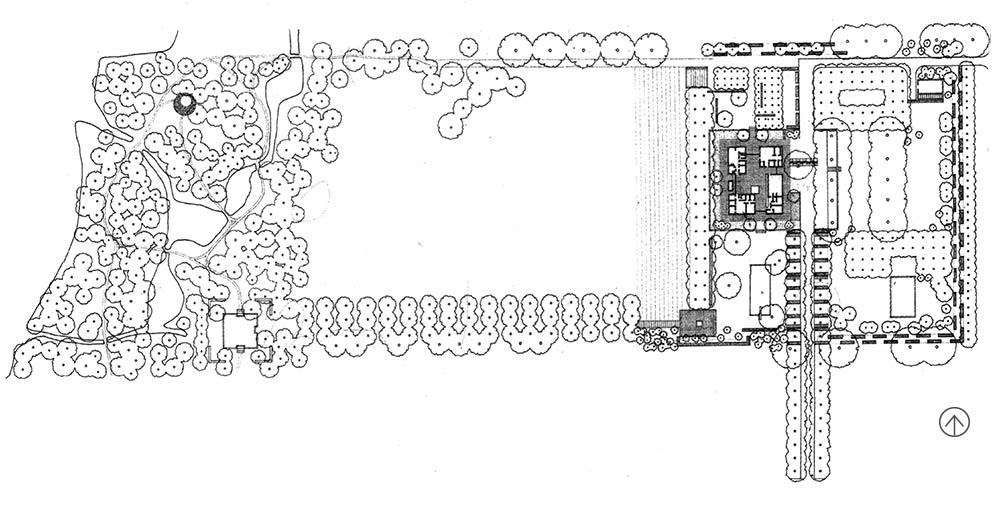

The house’s interior is arranged around a cruciform grid of steel columns. Kiley worked with the architects to create a seamless connection between the interior and the landscape, setting the home atop a twenty-five foot wide platform on which sits a ten-foot wide terrazzo terrace. The terrace acts as a physical bridge between the interior of Saarinen’s rectilinear structure and the garden, providing a setting for outdoor gatherings and dining. Extending from the patio to the edge of the platform are beds of ivy groundcover, periodically broken through by pavers set in gravel. Two weeping beeches are planted at the edge of the patio to the west of the house, adding height and movement to the space.

The garden contains three distinct sections – to the east, the most formal section of the landscape consisting of the house and gardens; at the center, a transitional area created by an open meadow – a mown lawn edged by red maples twenty-seven feet on center (originally proposed as an allée of sycamores, three rows deep and twenty-feet on center); and to the west woodlands bisected by a creek.

The landscape’s geometric design reflects the home’s interior geometry. The formal garden spreads out to the north, south and east of the house, along a low bluff at the eastern end of the site. The space includes bosques of apple trees and a pool area (constructed in 1963 after completion of the house), and the home’s formal entry drive which is lined with horse chestnuts under-planted with yew hedges that further emphasize the structural qualities of Kiley’s design. A series of arborvitae hedges in twenty-foot lengths are staggered along the perimeter of this section of the landscape, providing a loose barrier between the estate and neighboring properties. The hedges provide a false sense of enclosure while in actuality still leaving the borders of the property open.

The landscape’s most prominent feature is an allée of honey locusts that define an axis along the west side of the house and extend almost to the limits of the property. Historically, sculptures by Henry Moore and Jacques Lipchitz, acquired in the early 1970s, anchored the two ends of the axis. Finely textured, buff-colored crushed stone contrasts with the dark green of the honey locust leaves. Edged by a row of red maples, an open, managed meadow slopes toward the creek, ultimately becoming a natural wooded area.

The landscape’s most prominent feature is an allée of honey locusts that define an axis along the west side of the house and extend almost to the limits of the property. Historically, sculptures by Henry Moore and Jacques Lipchitz, acquired in the early 1970s, anchored the two ends of the axis. Finely textured, buff-colored crushed stone contrasts with the dark green of the honey locust leaves. Edged by a row of red maples, an open, managed meadow slopes toward the creek, ultimately becoming a natural wooded area.

In 2000 the Miller property was designated a National Historic Landmark. The property was the home of Mrs. Miller until her death in February 2008. The Moore sculpture and other artwork from the estate were sold at auction in the summer of 2008, and the following year the Miller family donated the property to the Indianapolis Museum of Art. The Museum then opened the property to the public in 2011.

The museum has established itself as an excellent steward of the site, setting a high standard for the curatorial treatment and management of Modernist landscape architecture. Their example is worthy of study, praise, and emulation by other stewards.

1 Frankel, Felice and Jory Johnson, Modern Landscape Architecture: Redefining the Garden (New York, London, Paris: Abbeville Press Publishers, 1991), 112.

2 Martin, Douglas, “Dan Kiley, Influential Landscape Architect Dies at 91,” The New York Times, February 25, 2004.

3 Kiley, Dan. “Lecture”In Dan Kiley Landscapes: The Poetry of Space, ed. Reuben M. Rainey and Marc Treib (Richmond, CA: William Stout Publishers, 2009), 26.

Peter Walker, FASLA, 2013

Discovering the Garden

In the spring of 1956 as a first-year graduate student at the University of Illinois, Champaign-Urbana, I attended a lecture by Daniel Urban Kiley of whom I had never heard. Mr. Kiley gave a charming and witty talk accompanied by perhaps the worst collection of obviously amateur slides I had ever seen. At the end of the lecture Mr. Kiley asked if any of us owned a car and might give him a ride to a project he was working on in Indiana. I offered my olive green Volkswagen bug, and early the next morning we were off, driving southeast through the Illinois cornfields on the brick country roads. After a wonderful lunch of steak and salad with, as I remember, two gin martinis, which he paid for, we arrived in Columbus and walked through the half-finished garden as Kiley discussed the issues with the contractor and occasionally explained design details to me. I found the afternoon interesting but otherwise unremarkable. The garden was, of course, to become the Miller garden.

Over the next decades, due to the Millers’ security concerns for their young children, the project was not published except for a brief architectural review of the house designed by Eero Saarinen. In 1975 I was teaching at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. With a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts we commissioned Alan Ward, the great photographer of landscape architecture, to photograph the garden, and we made the results into an exhibition, which was hung in the lobby of Gund Hall. I believe this was the first formal public presentation of the Miller Garden. The images of the now-mature garden were fantastic and generated great interest. In 1996 Melanie Simo and I had included a chapter on Dan in our book Invisible Gardens, and in 1999 Spacemaker Press published Ward’s photographs, along with others by Ezra Stoller, in a book, The Miller Garden: Icon of Modernism, featuring essays by Gary Hilderbrand and David Dillon.

By this time Dan and I had become great friends. I considered him my most important mentor. We had travelled together: He introduced me to the work of Andre Le Nôtre and the gardens at Villandry, Sceaux, and Chantilly. These gardens changed my life, just as, years before they had changed Dan’s, when he encountered them after his service in World War II. Dan visited many times with our students at Harvard and afterward at his home and office in Charlotte, Vermont.

Dan had become famous. In my judgment he is the greatest landscape architect in the last half of the twentieth century. And from that lecture in 1956 to his death in 2004 he offered me continued advice, support, and most importantly, his example.While the Miller house has fallen away in modern architectural history, the garden has remained as Dan’s most important work and, along with Thomas Church’s Donnell Garden in Sonoma, California, one of the two true masterpieces of the modern landscape movement.

Indianapolis Museum of Art. “Miller House and Garden in Columbus, Indiana,” http://www.imamuseum.org/visit/miller-house.

ArchDaily. “AD Classics: Miller House and Garden/Eero Saarinen,” http://www.archdaily.com/116596/ad-classics-miller-house-and-garden-eero-saarinen/.

Dwell. “Miller House in Columbus, Indiana by Eero Saarinen,” http://www.dwell.com/house-tours/article/miller-house-columbus-indiana-eero-saarinen.

Loos, Ted. “Inventing the Modern Garden: The Miller House and Garden,” Garden Design, http://www.gardendesign.com/places/miller-house-dan-kiley.

Thayer, Laura, Louis Joyner, and Malcolm Cairns. “National Historic Landmark Nomination: Miller House http://www.nps.gov/nhl/designations/samples/in/miller.pdf.

Bleam, Gregg. “Modern and Classical Themes in the Work of Dan Kiley.” In Dan Kiley Landscapes: The Poetry of Space, ed. Rueben M. Rainey and Marc Treib (Richmond, CA: William Stout Publishers, 2009), 78-97.

Kiley, Dan and Jane Amidon. Dan Kiley: The Complete Works of America’s Master Landscape Architect (Boston, New York, London: Little, Brown and Company, 1999), 20-27.

“Landscape Design: Works of Dan Kiley.” Process: Architecture 33. (Tokyo: Japan, Process Architecture Publishing Co., 1982), 21-26.

The Cultural Landscape Foundation. “What’s Out There: Miller Garden,” http://tclf.org/landscapes/miller-garden.

.jpg)