The Modernist Landscapes of Washington, DC

The Monumental City

At the turn of the 20th century designed landscapes in Washington, DC, followed established traditional tastes: monumental figurative statues on pedestals surrounded by colorful flower beds, formal and axial layouts, and a profusion of grand stairs, terraces, and water features. By the 1970s, designed landscapes in the District of Columbia reflected a very different aesthetic: these are the modernist landscapes.

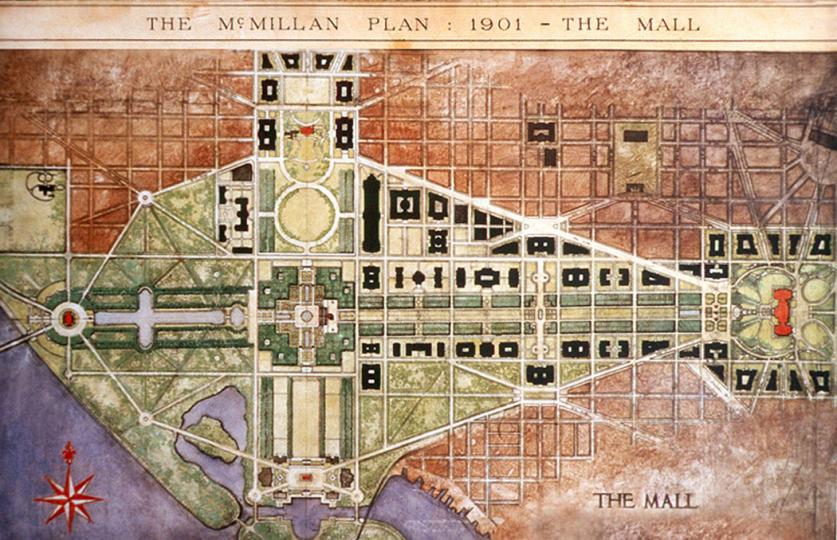

Because of its unique position as the capital city, the character and design of Washington, D.C. is a subject of great interest to Congress. The Federal Government built many buildings in the city and took measures through the passage of regulations, creation of entities, and congressional oversight to direct the style and appearance of public buildings and grounds. While this direction was piecemeal in the 19th century, direct oversight and official stated preferences for particular styles of architecture were the norm in the 20th century. The 1902 Senate Park Commission Report, the McMillan Plan, proposed that the National Mall function as the monumental core with public buildings organized around it in a formal geometry. From the Mall the proposed regional park and parkway system emanated outward along the banks of the Potomac and Anacostia Rivers and inward into the fabric of the city. The parkways would provide ceremonial entrances in and out of the city. In 1910 Congress created the Commission of Fine Arts (CFA) and the National Capital Park Commission (NCPC) in 1924 to oversee park development in the capital consistent with the 1902 McMillan Plan. To underscore the desired effect, the 1926 Public Buildings Act authorizing construction in the Federal Triangle included the phrase: “...said buildings should be so constructed as to combine high standards of architectural beauty and practical utility.”

From Monumentalism to Modernism

Between the 1920s and 1940s, there was a discernable but gradual movement away from the monumental architecture proposed in the McMillan Plan towards a more streamlined design. Most of the buildings were Beaux-Arts, monumental or classical in form, but Art Deco or Art Moderne details ornamented the facades and doors, such as can be found in the Internal Revenue Service (1930), Department of Commerce (1932), U.S. Department of Justice (1935), and the Adams Building (1939). As for the comprehensive park and parkway system envisioned in the Plan, the George Washington Memorial Parkway (1930-1960s), designed by landscape architects Gilmore Clarke, Wilbur Simonson and engineer Jay Downer, with input from Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., was one of the first built, although not completed to its full length until the 1960s. Rock Creek Parkway (1936) soon followed. Other parks built in the 1920s and 30s included East and West Potomac Parks and Anacostia Park.

One notable residential project from the early modernist period is Langston Terrace Dwellings in northeast Washington, D.C., located between H Street, Benning Road, 21st and 24th Streets. The development is a remarkable example of an International style residential complex designed and built by African Americans. The development was constructed between 1935 and 1938. Funded by the Public Works Administration (PWA) Housing Program, the 274-unit complex was the first such project in the nation’s capital and the second in the United States. The buildings were designed by Hilyard Robinson and Paul Williams, of the firm Robinson, Porter and Williams, and the landscape designed by David Williston. The complex was conceived of and built for aspiring and upwardly mobile African American families.

An early sign of modernist sensibilities that would soon break away from established tradition in public realm design is the elegant Mellon Fountain located in a triangular reservation at the intersection of Pennsylvania and Constitution Avenues with 6th Street opposite the National Gallery West Building north entrance. Here, the fountain is placed off-axis allowing an unobstructed view of the building façade. The 1952 landscape plan designed by the firm Clarke, Rapuano & Halloran consisted of four elm trees and ground cover to render the site attractive in winter months. The angular plaza for the Simon Bolivar statue (dedicated 1959), located at 18th and C Streets, contains an angular plaza with a trapezoidal shaped fountain pool and steps with minimal planting; features characteristic of spare modernist design. Two firms, Faulkner, Kingsbury & Stenhouse, a local architectural firm, and the New Orleans architectural firm of Favrot, Reed, Mathes & Bergmand, are credited with the design. An example of early modernist design that melded building with site is the Federal Office Building 6, Department of Education, constructed between 1959 and 1961. The International Style building was designed by firms Faulkner, Kinsbury & Stenhouse and Chatelain, Gauger & Nolan. The original setting and plaza, designed by landscape architectural firm Collins, Simonds & Simonds, integrated and balanced the building entrances within the triangular-shaped site. Today, this design has been largely replaced by the Eisenhower Memorial.

During the decades of the 1960s and 1970s, prominent American landscape architects, came to Washington, D.C. and worked collaboratively with modernist architects. Lester Collins, M. Paul Friedberg, Dan Kiley, Ian McHarg, Wolfgang Oehme, Hideo Sasaki, Eric Paepcke, Edward Stone, Boris Timchenko and James van Sweden designed public and private projects throughout the city. It is through the work of these practitioners that the modernist landscape flourished. Their designs experimented with axial organization and trapezoidal forms (e.g. Federal Reserve Board Garden), ushered in asymmetrical compositions, and tested new approaches and technologies for non-living (hardscape) and living (trees and shrubs) materials.

Urban Renewal Provides Impetus for Modernist Design

The modernist landscapes might not have been built if it were not for the post World War II massive urban renewal plans that designated huge swaths of the city fabric as blighted and in need of redevelopment. The use of eminent domain to gain control over privately owned lands was required to implement such plans but the public purpose and intent had to be established prior to the land acquisition. In 1945, enabling urban renewal legislation put forth both intent and planning process. The District of Columbia Redevelopment Act of 1950 provided for the establishment of the District of Columbia Redevelopment Land Agency (RLA) and the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC) to master plan, guide, fund and oversee the redevelopment of the city. NCPC prepared the first comprehensive city plan in 1950, entitled “Washington Present and Future” under the direction of Chairman Harland Bartholomew. The plan looked beyond the monumental core of the McMillan Plan, included regional highways and mass transit, and identified three sectors for urban renewal, Southeast, Southwest and Northeast.

The final guiding document was a product of three planners and Elbert Peets, a landscape architect. Peets, who had decades of city planning experience, developed the initial master plan that incorporated many of the historic areas in the quadrant and proposed retaining some of the existing residential buildings. Chloethiel Woodard Smith of Keyes, Smith and Saterlee, a local architectural and planning firm specializing in modernist design, joined forces with planner and architect Louis Justement and proposed a higher density alternative. The NCPC, under Harland Bartholomew, presented a plan to the District of Columbia that combined elements of both plans including a mix of townhouses and “elevator” buildings forming lower and higher density neighborhoods with services and parks.

NCPC oversaw the preparation of detailed urban renewal plans of which the most notable was the 1956 Southwest Development Plan, Sector C, a 600-acre area located south of Independence Avenue and intended to be a complete community with four components:

- The Tenth Street Mall linking Southwest Washington to the rest of the city;

- The Plaza providing a unified cultural and entertainment area;

- The Waterfront which included commercial and public uses of interest for the Capital as a whole; and,

- The Residential Neighborhood which was to provide a model community to serve family living in all its needs.

The RLA focused first on the residential neighborhood area, a “blighted” area within sight of the Capitol and home to a sizable African American population living in the bustling low-scale neighborhoods served by local businesses amidst badly congested streets. To encourage design innovation, the RLA held design competitions.

Winning proposals included Capitol Park (1961), designed by Chloethiel Woodard Smith and landscape architect Dan Kiley, which was the first residential urban renewal project. It set the stage for other modernist urban renewal developments in southwest Washington. Projects built between 1961 and 1966 include: Tiber Island, designed by Keyes, Lethbridge and Condon and landscape architect Eric Paepcke; Carrollsburg Square designed by Keyes, Lethbridge and Condon; Harbour Square designed by architect Woodard Smith and landscape architect Dan Kiley; River Park designed by Charles Goodman with Eric Paepcke, and Town Center East Park designed by I. M. Pei, courtyard by Zion and Breen. Public parks in the interior of the southwest redevelopment area include Lansburgh Park (1964) designed by LeRoy Skillman and the Town Center Park (now the Southwest Duck Pond) designed by William Roberts of Wallace, Roberts McHarg and Todd (1972). Waterfront Park (1972) designed by Sasaki, Dawson DeMay added public parkland along the Potomac River.

The NCPC developed the Northeast Development Plan in the 1960s, including Harland Bartholomew’s proposed Fort Lincoln New Town Development Plan. Fort Lincoln Park, designed by M. Paul Friedberg in 1971, was one of the few projects that came to fruition.

Promoting Excellence in Federal Design

There was widespread interest in ensuring that the capital city continue to reflect design excellence. President John F. Kennedy established the Ad Hoc Committee on Federal Office Space, which published Guiding Principles for Federal Architecture in 1962. The document encouraged federal planners to build structures that “reflect the dignity, enterprise, vigor and stability of the American National Government” and “embody the finest contemporary American architectural thought.” President Lyndon Johnson’s Administration added the landscape setting to the Ad Hoc Committee’s responsibilities for oversight of federal buildings and grounds:

Landscaping is included as an integral part of the design of any building and appropriate instructions are given in this respect during the design stage to contract architects and engineers. As part of these instructions, the architect is told to make his design in keeping with the motif of the community.

Modernist design had entered the design vocabulary for federal agencies just a few years earlier during the Eisenhower Administration. Conrad Wirth, Director of the National Park Service, initiated the modernization program, Mission 66, to improve the visitor experience at national parks timed to celebrate the Park Service’s 50th anniversary. Modernization efforts included improving visitor centers and developing a modern “park architecture” palette for new construction. Two notable examples in Washington, D.C., are the Henry T. Thompson Boat Center (1960) and the Carter Barron Amphitheater, both designed by architect William Haussmann, whose designs melded building and site. An early example of modernist design in a public park is National Park Service landscape architect William Bedlin’s modernist design for Bryce Park (1962) which featured concrete walkways, curved steel benches and slender lighting fixtures. The Great Flight Aviary (1964) at the National Zoo, designed by architect Richard Dimon of Daniel, Mann, Johnson and Mendenhall, is another example of the modernist design vocabulary in a public setting.

The late 1960s/1970s saw construction of several federal office complexes downtown, most notably Marcel Breuer’s iconic building, the Robert Weaver U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (1968), for which Breuer designed a plaza over the underground parking. Other significant landscapes include the Theodore Roosevelt Federal Office Building (1963) designed by Hellmuth, Obata and Kassabaum, with landscape architecture by Sasaki, Walker & Associates; Dan Kiley’s design for Banneker Park, formerly the 10th Street Overlook (1967) and the terminus of the original design for the L’Enfant Promenade, part of the Southwest Development Plan; Edward Stone’s elegant landscape plan for the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts (1971); and the adjacent residential Watergate Complex (1971) landscape design by Boris Timchenko.

Modernist landscapes were fashioned for art museums on the Mall. The Hirshhorn Museum’s Sculpture Garden (1974, 1977-1981) originally designed by Gordon Bunshaft of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill was updated by landscape architect Lester Collins. The modernist granite block pedestrian plaza that connects the East and West Buildings of the National Gallery of Art was a collaboration of architect I. M. Pei and Dan Kiley (1977).

Modernism also took hold in the planning and design of gardens at the National Arboretum beginning with the 1978 master plan by Sasaki and Associates, the Japanese Stroll Garden and Bonsai Pavilion designed by the firm’s Masao Kinoshita, the Friendship Garden by Oehme, van Sweden and the National Capitol Columns, sited by Russell Page and installed by EDAW. The plantings in the Federal Reserve Board Garden, originally designed by George Patton in 1974 did not survive the severe winter of 1977. Oehme, van Sweden revised the design, refining the circulation and site detailing while ushering in their signature “New American Garden” of planting with broad sweeps of materials of varied textures and shapes that were also better at adapting to surviving severe winters.

Landscape architects used a modernist vocabulary to design three presidential memorials. M. Meade Palmer’s modernist approach to the Lyndon Baines Johnson Memorial Grove (1973) was situated at a spot favored by the President and Mrs. Johnson because of its panoramic view of the Federal city. John Carl Warneke designed a modernist setting for the John F. Kennedy Gravesite (1967) in Arlington Cemetery at the request of former First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy. Lawrence Halprin created a narrative rich series of outdoor rooms in his competition winning design for the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial (1974). Here Halprin’s circulation plan drew visitors through a sequence of compressed architectural spaces depicting Roosevelt’s life set within the vast greenery of the Tidal Basin.

Architectural critics in the local and national press had much to say about Modernism. Breuer’s Weaver Building, in particular, was met with both high praise and harsh criticism. While the building was declared remarkable, Breuer’s empty curvilinear plaza at the front of the building had no seating areas. Martha Schwartz’s 1990 redesign attempted to bring a more humane scale to the expanse and provide much needed shade.

Modernist Landscape Architects Play a Prominent Role in Shaping the Public Realm

First Lady Claudia Alta "Lady Bird" Johnson (1963-1969), was not only a champion of conservation efforts and city beautification but appreciated the contributions of landscape architects and sought their advice and invited them to participate on various committees tasked with landscape improvements. She lobbied for the passage of environmental legislation and campaigned for the improvement of the character of the nation’s highway system. She was also involved in a number of modernist projects including a playground, Capper Plaza, by architects Pomerance & Breines and M. Paul Friedberg, with unusual modernist play sculptures by William Tarr.

The First Lady’s Beautification Committee convened monthly and over the course of four years planted azaleas and two million daffodil bulbs along the Potomac River and in the medians and triangles of the capital city and 200,000 bulbs along the Rock Creek and Potomac Parkway.

Columbia Island, a constructed island situated in the Potomac River, had vistas of the city and the landscape on either side of the George Washington Memorial Parkway, and was an ideal candidate to display Lady Bird’s highway beautification initiative. Edward Stone designed a planting plan for the 200-acre park, which was renamed Lady Bird Johnson Park.

A series of master plans in the 1960s-1970s recommended strategies to revitalize the public landscape. These included Skidmore, Owings & Merrill’s National Mall Master Plan (1966) for the National Park Service that proposed reducing automobile traffic and eliminating cross streets and the NCPC’s study, “Toward a Comprehensive Landscape Plan for Washington, D.C.,” prepared in 1967 by Wallace, McHarg, Roberts and Todd, which served as an early example of a comprehensive city-wide landscape plan. The study was included in the NCPC’s 1974 “Proposed Comprehensive Plan for the National Capital,” often referred to as the “Green Book,” which encouraged the use of natural landscape features to emphasize and better define Washington’s identity.

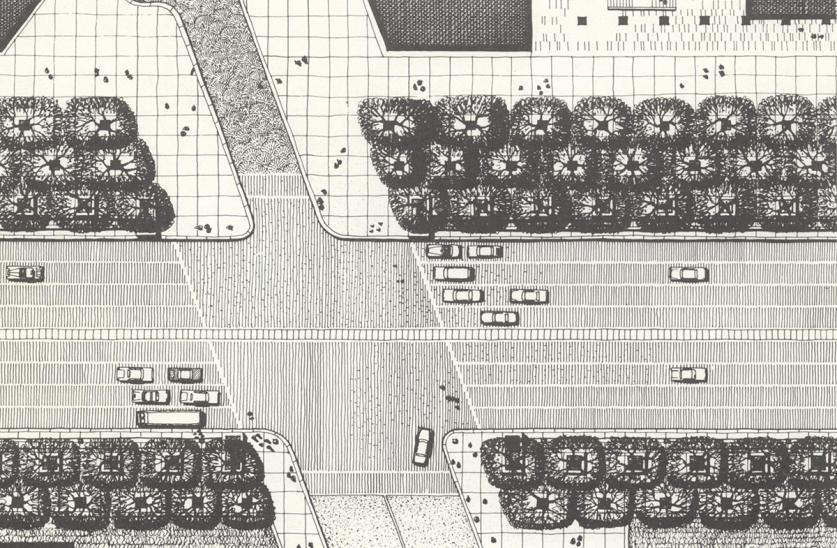

The Pennsylvania Avenue Redevelopment Authority, established in 1972 after a decade of discussion about the disrepair of America’s Main Street, was directed to “develop Pennsylvania Avenue in keeping with its historical and ceremonial role." The Authority, which was responsible for the redevelopment of the avenue into a grand urban boulevard, engaged Sasaki and Associates to develop a Landscape Master Plan specifying the types of street furniture, street lighting, paving and tree plantings. The proposed boulevard treatment was implemented by a triple row of street trees and today is most visible between 3rd Street SW and the Pedestrian Mall in front of the White House.

Modernist parks sprouted up along Pennsylvania Avenue including Freedom Plaza (1980), designed by Venturi, Rausch and Scott Brown with landscape architect George Patton and M. Paul Friedberg’s design for the adjacent Pershing Park (1981). This was followed by John Marshall Park (1983) by Carol R. Johnson and its contiguous neighbor the Canadian Embassy by architect Arthur Erickson with landscape architect Cornelia Hahn Oberlander (1989).

Other modernist landscapes and plazas include Liberty Plaza (1977) designed by Sasaki Associates (Masao Kinoshita, Tom Wirth, and Neil Dean) along 17th Street NW and the outdoor plaza around the addition to the National Geographic Society Headquarters (1981) designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill working with artist Elyn Zimmerman and landscape architect James Urban. Perhaps the most intimate modernist design for a public memorial was Maya Lin’s design for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial (1982). The experience of the design, which blended a v-shaped granite wall naming fallen soldiers into an earthen mound, is considered by many to be uniquely personal.

Modernism Falls out of Favor

By the 1980s critics of urban renewal and its deleterious effects on neighborhoods attributed characteristics of modernist design, such as abstract forms and hard surfaces, to designers’ indifference towards human needs and associated modernism with the destruction of neighborhoods and communities. This criticism coupled with a rising interest in historic preservation and conservation and local activism turned public opinion against modernism. Landscape architects confronted these challenges and developed a more nuanced, complex, and contextual approach to managing change through design. Local and federal redevelopment projects used multi-disciplinary teams to engage local citizens, constituents and stakeholders in the evolving design process.

All landscapes age and modernist landscapes are no exception. Many of these places, already suffering from diminished maintenance, reached the forty-year mark by the mid-1990s. Because a great number of these were in the public realm and often associated with federal buildings, refurbishing and updating these landscapes, especially when their historic significance could be determined, could result in a public review process that weighed both historic preservation and environmental considerations leading to determination of eligibility for listing in the National Register of Historic Places.

By the end of the first decade of the 21st century there was a resurging interest in modernist landscapes. As the landscapes have had to be made accessible, rehabilitated, and replanted, there has been a concerted effort to document, interpret and renew the bold and dramatic use of materials and the complexity and layering of design elements. These public landscapes continue to provide opportunities for people to experience the unique features of this fascinating period in American landscape design history in which art and landscape merged.

Acknowledgements

This digital guide to modernist landscape architecture in Washington, D.C., provides information about dozens of sites in the nation’s capital and their designers. It was created as part of the mitigation of adverse effects identified pursuant to Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act associated with the creation of a World War I Memorial in Pershing Park, a modernist park on Pennsylvania Avenue. This information is made available free of charge to the public via The Cultural Landscape Foundation’s (TCLF) website.

There are several individuals who were essential to spearheading this effort: Catherine Dewey, Chief, Resource Management, National Mall and Memorial Parks, National Park Service (NPS), who shepherded the project from the beginning, helping to realize the Cooperative Agreement and laying the foundation for the work that followed; Caridad de la Vega, Cultural Resource Program Manager, National Mall and Memorial Parks, NPS, who oversaw the peer review process; and, Julie D. McGilvray, Preservation Services Program Manager, NPS, and C. Andrew Lewis, Senior Historic Preservation Specialist, D.C. Historic Preservation Office, who provided helpful comments and suggestions.

At TCLF we are grateful to the project management by Charles A. Birnbaum, FASLA, FAAR along with Piera Weiss and Nord Wennerstrom. Project design and layout were executed by Justin Clevenger at TCLF.

Looking forward, the project team hopes that the D.C. Modernism guide will inspire similar efforts in other cities, not to mention an increased understanding and valuation for this unique and irreplaceable design legacy.